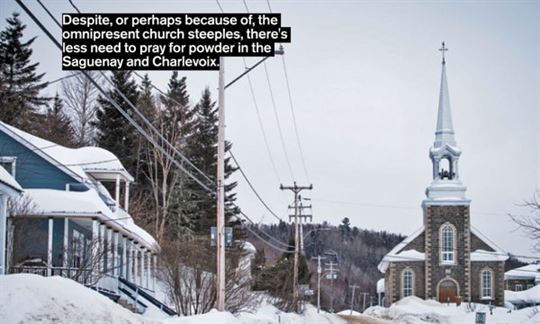

OAKLAND ROSS discovers three powdery hidden gems in the Charlevoix and Saguenay.

‘‘When we talk about snow, we don’t talk in centimetres here; we talk in metres. ’’

Photos MARK MACKAY in Buyer’s Guide 2018 issue

Along with a handful of English-speaking skier-journalists and a Scottish-speaking photographer, I had come to Quebec to explore a trio of ski resorts that few people beyond the province’s borders have ever heard of.

Thanks to the wonders of micro-climates, all three of these mountains—Mont Grand-Fonds, Mont-Édouard and Le Valinouët—receive tonnes of snow, more than five metres per season on average. In fact, Le Valinouët, high in the Saguenay/Lac-St-Jean region, gets six. Not six feet. Six metres. Understandably, Le Valinouët makes no artificial snow at all. It says so, right there on the resort’s logo: “100% neige naturelle.”

MONT GRAND-FONDS

The sun finally broke through the clouds as three of us mucked our way down a double-black torture chamber called Le Mur—or The Wall—a steep and densely forested descent that came by its name the honest way, as in: “Wall /woll/ Noun. Any high vertical surface or facade, especially one that is imposing in scale.”

Our location: a little-known Quebec ski area called Mont Grand-Fonds, rising amid the majestic terrain of the Charlevoix region, a couple of hours’ drive north of Quebec City and not far from the town of La Malbaie.

Although not Rockies-huge, the topography of Mont Grand-Fonds is nothing to sniff at. Scribbled with 20 alpine trails, the mountain boasts 335 metres of vertical and eight hectares of challenging glade skiing in an area known as Lynx.

It isn’t a matter of size that attracts skiers to Mont Grand-Fonds, it’s a matter of terrain, much of which is rated extreme. Even more than the terrain, though, is the snow. By mid-February last winter, the mountain had already received nearly five metres, which is close to the yearly average. The accumulation included 45 cm of rice-paper fluff that had tumbled earthward in the 24 hours previous to our arrival.

“When we talk about snow,” one local powderhound told me, “we don’t talk in centimetres here; we talk in metres.”

Which brings us back to The Wall, whose high plummeting surface was buried beneath several metres of cumulative base and topped with impressive mounds of new snow, mostly untracked. Plus trees. Lots and lots of trees.

Pitch is one thing. Trees are another. Put them together, toss in a half-metre of new-fallen snow, and what you’ve got are three things to keep in mind all at once, which is about my limit. I know what the experts say: the snow is your friend, the pitch is your friend, the God-damned trees are your God-damned friends.

But this is not a story about friends. It’s a story about snow. Well, snow and trees.

Just then, a guided missile in human form suddenly materialized at my side in a burst of flying snow. Yves Bergeron was his name—his friends call him Paddy—and he was our guide that day: a bearded, 57-year-old bundle of hibernal morphology who can bomb down a double-black-diamond glade much the way certain sub-atomic particles, I think they’re known as neutrinos, are able to speed straight through the planet Earth without ever bumping into anything.

Yes, that’s a fairly apt metaphor for what Bergeron does. He races down through the trees without seeming to make any turns at all, and yet he never bumps into anything.

Well, almost never.

Anyway, he could tell I was struggling.

“Stay loose,” Bergeron told me. “It’s the most important thing.”

Easy for him to say.

There were four of us on that densely treed descent, including Paddy, who now suggested we ease our way over to the left side of the glade. The main face, he explained, was just a wee bit pitchy hereabouts, with a pente, or slope, of about 50 degrees. Farther to the left, he said, the gradient was a bit milder—about 40 degrees.

Sold.

Of course, when it comes to Quebec, I don’t think only of trees. I also think of food. Consider the small, rustic refuge at the summit of Mont Grand-Fonds, which serves fine, home-cooked lunches, but only on weekends. After a morning of some pretty challenging skiing, we trooped into the refuge, where the ebullient young chef, Jérémie al-Simaani Goulet by name, had generously agreed to prepare and serve our group lunch, even though it was a Tuesday. Working on a small wood-burning stove, Jérémie produced a sensational four-course meal, practically from scratch.

By the time the meal was finished, it was about 2:00 p.m.—time to buckle our boots and get back on the mountain. Paddy led the way, and we soon headed back into the trees, aiming for a shot he thought we’d find amusing, which is how we found ourselves on the double-black-diamond glade called Le Mur.

After a somewhat laboured descent of 450 metres, Le Mur was history, and we skied out along a slender catwalk that bore us through the snow-covered woods back to the base of the mountain. There we clambered onto the chair. We were going to do this all over again—not Le Mur this time but another only slightly less-challenging double-black-diamond glade called Le Nid-d’Aigle, or The Eagle’s Nest.

It wasn’t pretty, but I managed to get down with my dignity more or less intact. Later, we rounded out the day with a last run on a broad, black-diamond shot called Le Braconniers—steep, lots of snow, no trees.

Brilliant.

We spent that night at Fairmont Le Manoir Richelieu, a château in the monumental tradition of grand Canadian hotels.

MONT-ÉDOUARD

At 8:30 the next morning, we piled into our van and headed north, our route flanked by towering snowbanks. We were headed for the Royaume du Saguenay/Lac-St-Jean (the Kingdom of Saguenay/Lac-St-Jean), as the region is widely known in deference to a long and noble history. Our destination: a ski area called Mont-Édouard. With 450 metres of vertical drop, the resort was the largest on our itinerary, comparable in scale to, say, Mont Sutton in the Eastern Townships. Founded a quarter-century ago, Mont-Édouard has two quad chairs, 32 runs and 10 glades, plus a huge expanse of hors-piste or backcountry terrain, with more on the way. The mountain also boasts a FIS-certified super-G course called Le Tableau.

Situated near the town of L’Anse-St-Jean about 175 km north of Quebec City, Mont-Édouard is closed Mondays and Tuesdays. (Mental note: I must return for first tracks on a Wednesday after a storm….) But it is passably busy the rest of the week. Granted, when I say “busy,” I don’t mean that you’d expect to encounter anything as crass as an actual lift line.

The resort has gone through several different ownership structures over the years of its existence. According to Claude Boudreaux, who’s the general manager, Mont-Édouard now belongs to the local municipality. An affable fellow with a shaven pate and a strong, confident style on skis, Claude first led us down Le Tableau and then guided us across a snow-covered, man-made bridge that opened onto a huge gladed area called Le Nor-est. When we showed up, the ungroomed descent was still covered with plenty of untracked powder. The terrain got a bit pitchy here and there. But it was big, and there were hundreds of different lines. Mostly, though, it was just fun to ski. I managed to relax a little. That, plus a moderate dose of speed, seemed to do the trick, and Le Nor-est soon morphed into a piece of snow-covered cake.

After lunch, we clumped into the ski shop to fit ourselves out with skins and backcountry gear. We were aiming to ski La Vallée des Géants (the Valley of Giants), which cascades down 15 hectares of birch and pine forest, making it the largest of Mont-Édouard’s three hors-piste ski areas.

Our guides were a couple of local hotshots, Yanick Neron and Marc-André Houde, who helped us as we fumbled around with our free-heeled touring gear. Eventually we plunged into La Vallée des Géants, with its thickets of birch and pine, and deep folds of untracked powder. If heaven has snow and plenty of trees, then this was heaven. I had my best run of the trip.

We spent that night at a convivial little hostelry called La Maison de Vébron in L’Anse-St-Jean. At 7:00 or so in the evening, we trooped out into the darkness, aiming for a restaurant named L’Islet sur la Montagne, or Island on the Mountain, where a special St. Valentine’s menu was being served, even though St. Valentine’s Day had come and gone the day before. They say that everything sounds better in French—but this would have been a sensational meal in any language.

LE VALINOUËT

Early the following morning, we hit the road yet again, this time aiming for the final resort on our itinerary, a station du ski called Le Valinouët, located a two-hour drive away. We trundled along the south shore of the frozen Saguenay River, past substantial communities of ice-fishing huts. At Chicoutimi, we crossed the Saguenay and headed north past St-Honoré and St-David-de-Falardeau until we found ourselves at the base lodge at Le Valinouët, 245 km north of Quebec City and deep in the kingdom of winter. It was just mid-February, but Le Valinouët had already received about six metres of snow. No need for snowmaking here.

Le Valinouët boasts 350 metres of vertical and 30 trails, including five glades and six mogul runs. An instructor named Deny Tremblay and ski school director Michel Brassard—a.k.a. Deny et Mike—led us down a long blue cruiser as a warm-up, followed by a steep double-black descent and a double-black with moguls. Later, we dodged our way down a thickly gladed shot called La Yeti, which made up in trees what it might have lacked in pitch. On the other hand, according to the plan des pistes, La Yeti is rated a double-black diamond. So maybe it was me. Maybe I was finally getting used to this stuff.

Established in 1984, the ski complex at Le Valinouët is nowadays owned by a workers’ co-operative, on land that belongs to the municipality. There are plans for expansion and development, including a new base lodge plus a 50-unit condo-hotel.

The mountain at Le Valinouët has two separate skiable faces, one turned north and the other, northwest. The northwest face was closed on this day, but those who make such decisions agreed to fire up the quad chair so we could have a look. Along with a handful of local skiers, we descended upon the northwest face along a connecting route called La Jonction. The mountain had received plenty of new snow. Even better, a steady wind out of the north had swept the good stuff close to the tree blinds on the eastern side of the runs, roughly doubling its depth—30 cm or so of untracked powder—and no one around to enjoy it but us.

So we did.

START YOUR RESEARCH HERE

- Quebec Ski Areas Association, maneige.ski

- tourisme.saguenay.ca

- tourisme-charlevoix.com

- quebecoriginal.com