Have you ever zipped past snowboarders who couldn’t get enough speed on the flats in deep snow? If you love off-piste skiing as much as I do, I’m sure you’ve encountered this more than once.

Snowboarders’ lack of poles and inability to freely move their legs lead them to sink in deep snow as soon as the terrain gets slightly flat, and to struggle on technical traverses when precision is required. Having been both a skier and a snowboarder for years, and having experienced the effort of “swimming” out of deep snow, I can firmly attest that riding powder on skis is much more fun than on a snowboard.

Nevertheless, in my personal experience, skiing became more fun than snowboarding only in the new millennium when ski manufacturers introduced new shapes and constructions that radically changed the approach to this sport. Today, as an academic and 15 years after I freed my feet, I study where these innovations, which have so strongly affected ski manufacturing and skiers’ personal enjoyment, originated from.

‘‘In other words, snowboarders got it first and skiers followed snowboarders’ lead to create those wonderful tools that are simply commonplace today. ’’

The topic is broad and debatable, but one aspect I propose as certain is that, like it or not, all the fun we have carving, performing tricks and riding powder on skis is the result of knowledge that originated in the world of snowboarding, and that has been subsequently applied to the production of skis. In other words, snowboarders got it first and skiers followed snowboarders’ lead to create those wonderful tools that are simply commonplace today.

I know this is a serious claim, and you’re maybe thinking: “This guy’s got it wrong. It’s evident that skiing was around generations before snowboarding and that knowledge contamination flowed from ski to snowboard and not vice versa.”

Well, you might be correct in operational terms, in the sense that snowboard manufacturers looked at the ski production process and applied it to snowboards, but knowledge moved from snowboard to ski when we talk about innovation in product characteristics beginning in the 1990s.

Since this is not an academic work, I am not going to bore you with the sophisticated theories and statistical analyses that I collect for my PhD research. But I propose three pieces of evidence that, if they don’t convince you, should at least tickle your curiosity to know more about snowboarding as today’s source of our skiing enjoyment.

—————

- Think back to, or ask your parents or grandparents about, the 1970s and ’80s when skis had sidecuts ranging from six to nine mm, lengths of 200 cm and more (up to 230 cm for downhill racing skis) and turn radii around 40 metres. On another trajectory in 1975, Jake Burton was quietly introducing his Backhill snowboard with a 17-mm sidecut, 140-cm length and a six-metre radius. Compared to skis of the day, snowboards were obviously shorter and more carving-oriented. Although some experiments were made by ski manufacturers to apply a more extreme snowboard-like sidecut to skis, such as in the Olin Albert model in 1984, it wasn’t until 1991 that Elan’s engineers, Franko and Skofic, finalized a GS race ski. With its 22.25-mm sidecut and 15-metre radius, the deep sidecut started to replace the traditional shape as the ski industry’s dominant design. It took several years of fine-tuning to find the best tip-waist-tail ratios. As well, the ideal ski length dropped substantially—toward more snowboard standards.

—————

2. In the same way, twintips and wider widths have been adopted in skis years after they were used in snowboarding. “The design of skis hadn’t really changed in about 100 years…until snowboarding came around,” says Jason Levinthal, founder of Line and J skis, when describing the inception of skiboards and twintip skis. “Snowboarders weren’t interested in skiing down the hills. They wanted more to skateboard on the hills, so they designed a twintip tool that could be ridden forwards and backwards and allowed all kinds of tricks, just like a skateboard (unlike skis), and was wider to float on powder easily (unlike skis)… There was a constant evolution in snowboarding that did not exist in skiing. I always loved skiing but I just couldn’t do enough on my skis and I could do so much more on my snowboard. I thought: Why can’t I combine the best assets of a snowboard into a ski? Years later, I decided to design a ski that was like a snowboard, so I took a snowboard and cut its dimensions in half and made a ski!”

————

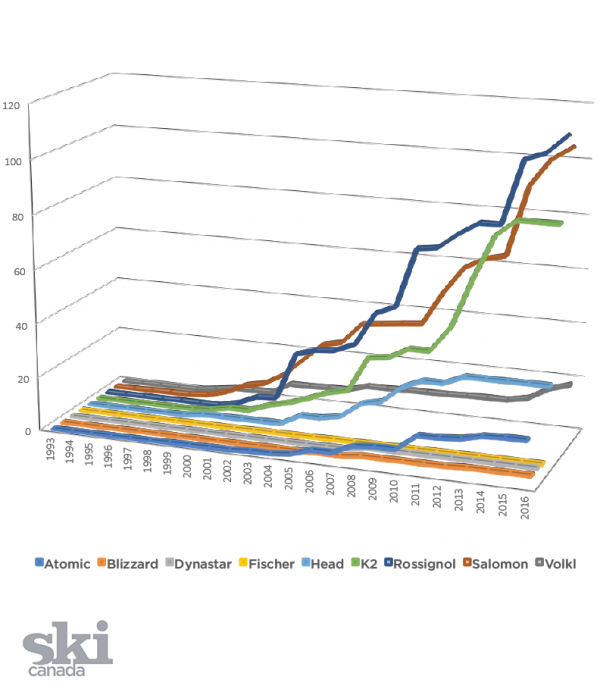

3. In a similarity analysis of each patent filed by ski manufacturers with each of snowboard-maker Burton’s patents, we can see in the graph shown here that skimakers’ cumulative interest in the snowboard-related world becomes heterogeneous starting in 1998. The graph shows that many ski manufacturers substantially explored the snowboard world, while others remained more ski-oriented.

—————

Although a more thorough analysis is required to address the impact that snowboard-related knowledge had on skis in terms of quality, innovation and performance, at first glance it appears that our ability to carve and leave our mark on untouched deep powder as well is the result of what snowboard manufacturers did more than two decades ago.

The next time you ski past a snowboarder struggling not to sink in powder, do not interrupt your endorphin-releasing powder line to stop and help him or her (that would be a sacrilege), but show a little empathy and buy a beer for the poor soul once you’re both at the bottom. It’s tough to admit—but true—that snowboarders got it first and we owe them our gratitude.