In everyday life, the ACL normally performs well but starts punching above its weight when the knee is exposed to a twist or torque—from, say, landing a jump, skiing moguls or suffering a forward twisting fall. In scenarios from complete beginners to World Cup racers, the ACL is vulnerable to injury—but more so in certain skiers.

by Lynda Cranston in the December 2016 issue

The ACL, or anterior cruciate ligament, is a mere three to four cm long and about as thick as your pinky finger. Yet this tiny piece of tissue that runs diagonally across the knee plays a huge role in preventing forward movement of the tibia (shinbone) on the femur (thighbone), as well as providing rotational stability to the knee joint.

For instance, women athletes are two to six times as likely to rupture their ACL. Hormones (that relax the ligaments), knee shape (that can pinch the ACL) and wider hips (that place more stress on the knee) are thought to play a role in the statistic. There are other culprits, too, such as heredity (the risk of ACL tears doubles if either of your parents had this injury) and modern ski equipment.

This all adds up to a less-than-rosy picture: ACL injury rates in skiing appear to be continuing to rise. And they can happen to skiers of all ages and levels, though more commonly at each end of the spectrum. “It’s a bimodal curve,” says Dr. Robert McCormack, an orthopaedic surgeon in New Westminster, B.C., who has been Chief Medical Officer at several Olympic Winter Games and works with the Canadian Alpine Ski Team. “Beginner skiers put their knees at risk because of poor mechanics. Expert skiers are pushing the envelope.”

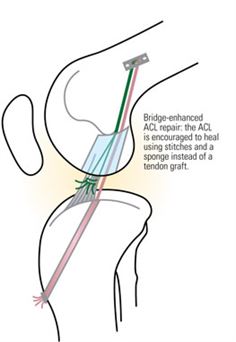

Except in rare cases, the ACL is just about the only ligament that can’t heal on its own because the fluid surrounding the ACL dissolves blood clots. Good on one hand since you don’t want blood clots inside your joints. But bad on the other since blood clots can stimulate healing by providing a bridge between the torn ends of the ACL over which new tissue can grow.

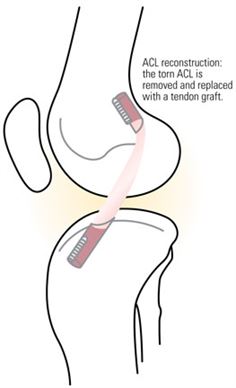

So when an ACL tears, there are two choices. Watch and wait, a conservative approach of bracing and physiotherapy. And surgery, a more predictable approach for knee stability, good range of motion and return to unrestricted, pivotal activities. Repair techniques conserve the “native” ACL; full reconstruction removes the torn ACL and replaces it with a new tendon.

Repair Job

Attempts in the 1960s and ’70s to repair ACLs typically failed due to technique and a tendency to repair all comers. By the 1980s, surgeons turned to full reconstruction, a procedure that has since remained at the forefront. But the operating theatre pendulum may be swinging back with renewed enthusiasm for ACL repairs in the past decade.

“There are definitely new frontiers in what we call biologics—hormonal and even cellular adjuncts—that are being used in some centres to repair ACLs,” says Dr. Mark Heard, an orthopaedic surgeon in Banff and consulting physician for Canadian snow sports teams.

One such procedure is the Bridge-Enhanced ACL Repair, being tested at the Boston Children’s Hospital. A tiny sponge is soaked with special proteins, stitched to both ends of the torn ACL and then infused with the patient’s blood to stimulate clotting and speed healing. Scientists have observed that the ends of the ACL grow into the sponge, reconnect and eventually replace the sponge. The hope is that there will be a shorter recovery time and that the chances of developing arthritis—common in patients who have a reconstructed ACL—will be lower. Although not yet available outside major research centres, this procedure holds much promise in the realm of ACL repairs.

Another repair technique that has already moved from lab bench to bedside is the internal brace. A band of high-strength, polypropylene tape is run up the centre of the torn ACL to span from shinbone to the thighbone. This tape acts as a brace to keep the ACL in place until it can heal biologically. Dr. Robert Timothy Deakon, an orthopaedic surgeon in Oakville, Ontario, as well known to Collingwood club skiers as he is to the Toronto Argonauts, has performed this procedure on three patients so far. “I really enjoy doing it,” says Deakon. “Philosophically, I think it’s better to retain the patient’s tissue that has innervation and blood supply. In the past we’ve always cut this out and put in a dead tissue graft. [A repair] makes more sense.”

Deakon admits it’s too soon to know if this technique will be successful in the long term—patients have to be followed for several years to know for sure. Repair techniques, like the internal brace, are not right for everyone. The best candidates have an ACL that is torn cleanly, close to the thighbone. What’s more, time is of the essence. Within a few weeks, the torn ACL stump begins to retract and shorten, so any repair must be done within weeks (likely three). And as Canadians across the country know, the wait times in our health-care system virtually preclude such timely access to orthopaedic care.

The jury is still out on whether any surgical repair is here to stay. “Procedures fall out of favour, come back into favour, then fall back out again,” says McCormack. “I think we need more data to know for sure if a recent trend is the right way to go.”

For now, however, full ACL reconstruction remains the gold standard in Canada. And the good news remains, there are plenty of improvements here and on the horizon.

The Goods on Grafts

The orthopaedic pendulum has swung back and forth when it comes to the best tendon graft source for full reconstruction. An allograft (tissue harvested from a cadaver) eliminates the use of a patient’s own tissue, but allograft failure rates can be four times that of autografts, where tissue from the patient is used. Still, there’s a role for allografts in patients with multiple knee injuries who can’t spare their own tissue. “You can only rob Peter so much to pay Paul,” says McCormack.

Typical autograft sources include the hamstring, quadricep and patellar tendon. For some time, the hamstring has been the graft of choice, but patellar tendons have become more popular with studies showing a lower failure rate and better stability of the knee. On the down side, patellar tendon grafts can result in greater loss of knee extension and more pain at the front of the knee, or patellar tendonitis—a common condition in skiers.

The make-up and condition of the patient is a big deciding factor. “If someone is ligamentously lax, the patellar tendon may be a better graft because it’s less likely to get stretched out,” says McCormack. But in a patient with patellar tendonitis, “the patellar tendon may be a bad choice because you’re messing with a tendon that already has a high risk of causing problems.”

Deakon points out that the quadricep tendon is a reasonable but under-used graft choice. McCormack reports using the quadricep tendon when doing an ACL revision: “On Tuesday I did one hamstring, one patellar tendon and one quadricep. They each have a role to play.”

Synthetic grafts are rarely used today, although a pig tendon, with the otherworldly name of Z-Lig, has shown promise, working as well statistically as an allograft patellar tendon. Z-Lig is a choice in Europe, South Africa and other countries, though not yet available in Canada.

Tissue culturing—growing a piece of a patient’s tendon into a new graft—may be the way of the future, according to Heard. He foresees competitive skiers having their tissue harvested at the start of their skiing career and, later, if injured, transplanting this tissue immediately. “I see that happening in ligaments and possibly even articular cartilage in the future,” he says.

Reconstruction Techniques Refined

All Inside ACL Reconstruction is a new technique that changes how the tendon graft is inserted into the knee. Previously, a deep tunnel was drilled from the outside surface of the shinbone up into the inside of the knee. However, both the larger incision needed to drill the tunnel, as well as the larger tunnel opening on the surface of the bone, caused significant pain post-surgery. Now, a surgeon makes a small socket using only a few tiny, arthroscopic incisions, reducing pain and scarring, and speeding recovery time.

The methods for anchoring ligament grafts have improved, too. “They just keep getting better and more minimally invasive,” says Deakon. “They don’t require as big an incision and are much more reliable.”

Another recent trend in knee surgery is extra-articular augmentation. This procedure, commonly performed in Europe, aims to make ACL reconstruction more stable by repairing the antero-lateral ligament (a ligament on the outside of the knee that’s almost always injured with an ACL rupture) with a strip of the patient’s iliotibial band (a band of fibrous tissue that runs down the outside of the thigh).

“An ACL-deficient knee wants to pivot or pop out,” says Heard. This technique will prevent rotational instability, he explains. Both Heard and McCormack are involved in an international study comparing 600 patients with and without this extra-articular augmentation to see if the new technique is a keeper. In the meantime, Heard is already using this technique in patients at high risk for re-injuring their ACL. “If I have someone now who is a national-level skier, I will augment them with it routinely,” says Heard.

Another augmentation technique combines an ACL repair with a smaller reconstruction. Partially torn ACLs are being repaired with a smaller-than-normal graft. “We shish-kebab it right up the middle of the torn ACL,” explains Heard. These patients do extremely well because their original ACL is retained, while the graft acts as a strut to keep it in place.

Fit To Ski

No surprises that the best approach to knee injuries is prevention. Start a pre-season conditioning program that works on your hamstring strength as well as your quadriceps. “You have to balance your thigh muscles,” says Dr. Deakon, an orthopaedic surgeon, in reference to skiers who frequently underestimate the necessary hamstring strength required. As well, make sure your bindings are mounted, adjusted and serviced by a technician. And learn how to lessen your risk of injury by visiting VermontSkiSafety.com to learn or refresh your knowledge on Phantom Foot Syndrome.

Twist and Shout

The well-known “pop” sound and feeling is the hallmark sign of an ACL injury, although your ACL can tear without it. You will have significant pain and swelling within the first few hours, and your knee may feel unstable.

Immediately after the injury follow RICE: Rest Ice Compression Elevation.

An MRI may not be necessary but always ask for an X-ray.

Get to a sports medicine doctor. He or she can provide a more accurate diagnosis, will be your best portal of entry into orthopaedic care and may get you seen faster if you’re an urgent case. Find a sports medicine doctor near you at casem-acmse.org.

Get Back Out There

Following an ACL reconstruction, a six-month break from high-risk activity involving pivotal sports has long been the norm. But even that time frame is changing. A recent Scandinavian study found that adding more rest made a big difference. It showed that more than half of ACL re-injuries were reduced for every month that return to sport was delayed—up to nine months. The take-away message? Quit the season early, book your surgery in February or March and wait until at least Christmas before you get back on-slope.

Of course, the best approach to knee injury doesn’t involve any breakthrough science but simply prevention. “We do a pretty good job of dealing with the ACL and restoring knee stability,” says orthopaedic surgeon Dr. Deakon. “But we can’t go back from a bad meniscus tear or a shearing injury to the joint surface where you lose a piece of cartilage. Those are much harder to fix.” Instead commonsense strategies, such as a pre-season conditioning program and knee-friendly skiing, are the surest route to lowering the numbers in the epidemic of knee injuries for skiers.