It turned out the prize was desert wasteland in New Mexico, and nearby the unique ski resort of Taos beckoned.

In the swinging ’70s, before America’s Got Talent or Instagram, folks had to find fame on their own terms. That meant one thing: The Price is Right. So never shy of a little noise and light, my friend’s mum Stella loaded up her kit bag with her Dippity-do and flared animal-print pantsuit and peeled out of Banff. Destination: Hollywood.

And didn’t Stella just have Bob Barker’s number: “C’mon down!” sidekick Johnny Olson boomed, “you’re our next contestant on The Price is Right!” Her mission: to choose one door for her fellow contestant, the remaining door would be hers to take home. For the man from Cincinnati? “A shiny new car!” For Stella, “A vacant quarter-acre parcel of land in a faraway land: Taos, New Mexico!”

Cue 2019. Long forgotten, never seen, 48 cents owing in back taxes—with annual property taxes of $5 a year, an understandable oversight—I accept the mission to track down the mystery mini-ranch and, at the same time, check out the major changes shaking down at one of America’s truly classic ski areas, Taos Ski Valley.

Like the always memorable Stella, known for wearing blinking Christmas lights in her hair and successfully ministering the family’s 1930s log cabin resort in Banff National Park, Taos’s new owner is attracting his share of attention, too. Maybe being a New York hedge-fund billionaire has something to do with it. Or perhaps it’s the juxtaposition: Louis Bacon has been called a modern-day moneybags with a conservationist bent.

Taos Ski Valley founder Ernie Blake—a German-born, Swiss-educated rebel who grew up skiing in St. Moritz—first spotted the steep north-facing pitches and demanding tree runs at the foot of mighty Mt. Wheeler from the air in his Cessna. Soon after the lift started turning in 1954, Taos launched onto the podium of classic American ski areas alongside Aspen, Jackson Hole and Sun Valley. But more recently, the long family-run resort had slipped into an unmodernized decline, and in 2013 hedge-funder and philanthropist-skier Louis Bacon scooped it up from financial heavy waters. No run-of-the-mill buyout, 63-year-old Bacon’s redevelopment plans are on track to shepherd Taos into skiing’s 21st century.

The skiing here tops out at just over a thin-air 3,800m on Kachina Peak—a deep-powder, 45-degree face with a new chairlift. Built in 2015, the Kachina chair was among the first of several capital improvements valued at a little under C$395 million and teed up by Taos’s new owner, alongside three further lifts and a pedestrian gondola to access a revamped beginner zone, base area and children’s centre.

Next to the welcome ski infrastructure upgrades is the new jewel-of-a-hotel, The Blake. Smack at the base of the village chairlift, at 2,841m elevation, the hotel has 80 rooms and suites over four alpine-elegant floors, a fabulous restaurant, an indulgent spa and a ski valet all within a few easy steps to the slopes. This winter, the fourth floor opens with several posh, extremely roomy apartments.

Occupying pride of place throughout every nook and cranny is what makes this an inn apart: the riches of Bacon’s private art collection, a beautiful and storied study of the local Taos Pueblo people, one of the oldest cultures on the continent. Beginning in reception, a jaw-dropping fiery landscape by Georgia O’Keeffe is flanked by Walter Ufer’s “The Watcher” (with more O’Keeffe drawings later). Then there’s an embarrassment of images from iconic Edward Curtis, renowned photographer of early 20th-century Native American life, some images previously undeveloped and unseen. Canadian Yousuf Karsh photography lines the walls of the spa, 10th Mountain Division artifacts abound, and the ski-loving, black-and-white, life-size photos of famous Dick Durrance command the landings.

My favourite objet, however, is among the most mundane: a hand-knitted pompom toque near the restaurant entrance. Circa 1980s, JANITOR is spelled across its headband. The hat belonged to Taos’s head janitor slash owner, renegade Ernie Blake, a reminder of what pioneering was all about before the Intrawests and the Vail Resorts came onboard with their ROIs, speed traps and facial hair bans on staff. A glance at the Taos trail map yields further clues about the Weltanschauung of Ernie and his friends. Stauffenberg, Fabian and Oster—all real, can-do characters and all associated with attempts on Hitler’s life—rub elbows with more of Blake’s heroes, Winston (as in Churchill) and Patton, under whose service in the OSS Ernie rather unwittingly uncovered valuable intelligence around the atomic bomb, informing his “anything is possible in America” philosophy.

Once you know a little about the man behind the myth, it won’t surprise that the soul of this ski area is about earning your turns. The great powder descents down the chutes off infamous West Basin and Highline ridges and most of the gnarly expert runs are still accessed only by hikes—from short five-minuters to long lung-busters frequented by dudes you’ll see later slinging tacos and margs at the Stray Dog Cantina in town.

No less than 50 per cent of Taos’s terrain is classed as expert, though with 110 trails and 15 lifts there are plenty of blue and green runs to go around, including one long lovely with five miles of continuous cruising. The snow is high, dry and north-facing, which translates to no melt-freeze and no icy crusts. Rather like Canada’s Red Mountain is to Whistler—fantastic, formidable, uncrowded skiing that’s overshadowed by its famous neighbour—Taos’s closest clientele rarely makes it over the Colorado border.

“Fill a space in a beautiful way” is how Georgia O’Keeffe regarded the role of art in the world. She made this part of New Mexico her own, painting its ochre skies and pink ranchscapes right into the American psyche. A high-desert home to Native Americans for more than a millennium, Taos has long been a crucible of the artistic, the wealthy and the free-spirited, drawn by the dreamy light and arid beauty of rolling mesas and surrounding peaks.

A visit or two to Taos’s many galleries and museums is a must on any ski trip. From the Millicent Rogers Museum, bequeathed by the maverick socialite herself—the docent shares a fantastic tale: when Millicent fled a broken love affair with Clark Gable, she dispatched him with a bottle of champagne and a goodbye note via a Hedda Hopper column—to the splendid Harwood Museum of Art, its origins thanks in part to Mabel Dodge Luhan who decamped from New York and Florence to establish a glittering modernist literary salon in the desert, whose luminaries included D.H. Lawrence, Martha Graham and Ansel Adams. Taos has won a reputation for drawing some of the world’s great artists, writers and, yes, even hedge-funders into the romance of its mountain-laced orbit.

En route to a delicious soak in the outdoor geothermic pools of Ojo Caliente, a half hour from town, we pull over to explore another of the area’s visual and spiritual phenomena. The otherworldly Earthship community, a sudden subdivision of large, loping houses constructed entirely of recycled tires, bottles and mud, lurches from the mesa, providing energy-conserving shelter (for rent by the night, as well as ownership) with ample room for Martians to land.

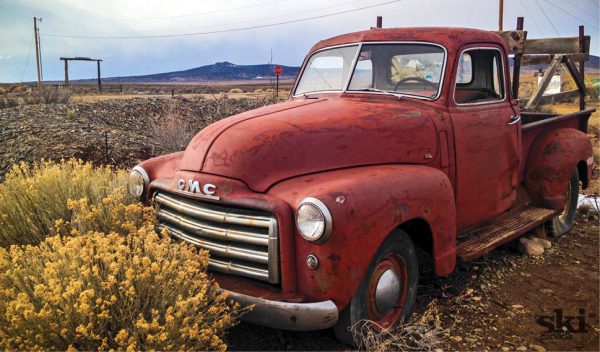

With the further aid of Google and an old tax bill, we round the corner where a murder of disused yellow school buses align in front of a flock of high-fenced double-wides. There, unsullied by human hand or developer’s digs, was Lot 14, Tres Piedras Estates—a game show gong dressed in fluttering sagebrush and poetic tumbleweed. All this potential Southfork of the Southwest needed was the same imagination and strength of character that so many other Taos arrivistes have shown for a place rich in natural wonders. A place where, I feel, the magnificent Stella could happily call home.