Capturing the beauty of South Korea was made easier with the new iPhone 11 Pro

Back in early December, North Korea’s black comedy of a Supreme Leader, Kim Jong-un, was testing another rocket. Not far away, photographer Adam Stein and I were in Seoul, South Korea, trying to convince our guide to take us off script for a tour of the DMZ or demilitarized zone that separates the two enemies.

Instead, we were going to a cabbage museum.

The DMZ and Cold War, as told by the South Koreans, sounded like a fascinating tour, but we were learning that snipers and drones had recently been mobilized. “Everything has been quarantined,” our guide Jay said emphatically. “You can’t go, DMZ closed!”

As it turned out, there was no need for us to seek shelter; the threat of invasion was from wild boars that had somehow managed to cross the DMZ fortifications. The Canadians must be protected from North Korean hogs, carrying African swine flu, from China. Just another Adam & Iain adventure.

Part of our missed DMZ tour includes wandering down one of the four so-called “Tunnels of Aggression” that were discovered between 1974 and 1990 when the North was planning on invading the South by digging. Tunnels ran as deep as 160 metres beneath the enormous wall, electrified fencing, landmines, audio disinformation, leaflets being dropped from propaganda balloons and four km of now ecologically naturalized no-man’s land. South Korea believes there are still as many as 20 more undiscovered tunnels, however, their importance has been somewhat lessened given today’s missiles and rockets are a little faster than marauders.

Nevertheless, in 1978, when Tunnel No. 3 was found 435 metres south of the DMZ, and only 44 km from Seoul, it was large enough to potentially move 30,000 men per hour, with weaponry. Or skis, I suppose. Most of the Korean peninsula is mountainous, and although Kim Jong-un and his half-brother (whom he murdered) learned to ski while attending school in Switzerland for four years in the late ’90s, he has a long way to catch up with South Korea in pretty much everything, including alpine skiing.

South Korea has 22 ski areas in total, the largest of which compare in size to big Quebec or maybe Okanagan mountains but with more developed infrastructure and surrounding base areas. Adam’s and my mission was twofold: to inspect a new ski area each day and photograph them with our iPhones. A challenge, indeed, given only the bottoms of one or two runs were open at each ski resort, the best offering a layer of edge-deep manmade.

“It says Korea’s largest ski resort Yongpyong is in Pyongchang!” Adam blurted out excitedly after reading something on his phone. “That’s the capital of North Korea right!?” Defending himself later, Adam said, “I’ve never watched Kim’s Convenience, but you have to admit, Pyongchang and Pyongyang do look similar.”

On a map, I suppose the county of Pyongchang, is relatively close to North Korea, but it’s a world away. Adam later felt vindicated to learn that the 2018 Olympic bid committee, fearing similar confusion for other foreigners, purposely changed the western spelling of the county’s name to include an e and a capital C—“PyeongChang”—to try to differentiate the two; plenty of leftover spellings abound, however.

Within PyeongChang county (about 200 km east, not north, of Seoul) lie several ski areas such as Yongpyong (Dragon Valley), host of the slalom and GS events at the 2018 Games. With 15 modern lifts, 28 slopes and a vertical of 738 metres, top to bottom is close to that of, say, SilverStar or Big White. But you don’t go to Korea for heaps of Okanagan champagne powder; winter weather on the peninsula is dry, sunny and cold, perfect for making snow in a machine, not in the heavens. And in classic Korean style, perfect groomers that are redone during the ski day. Should a big dump happen to arrive during your visit, skiing in the trees is not only forbidden, it would be impossible since many runs are sided with plastic netting to prevent any off-piste incursions.

It was only after we returned home that we learned Yongpyong is owned by the Unification Church, or for those growing up in the 1970s and ’80s, a.k.a. the Moonies. Both of my sisters, while travelling the U.S. after university at different times, had fun but disturbing stories about resisting indoctrination by the proselytizing followers of Rev. Sun Myung Moon. And a friend’s brother had to be “deprogrammed” after being kidnapped from what at the time was considered a cult and returned to Canada, so it was fascinating to later read the movement’s financial spiderweb includes Korea’s biggest ski resort.

With the offspring of Rev. Moon taking an obviously broader approach to business from decades ago, I wondered if any signature mass-wedding ceremonies of matched couples had occurred at the resort. I imagine with skiing into the wee hours of the morning, a five-star hotel, high-rise condos and budget accommodation, a massive indoor water park, 45 holes of golf and a huge choice of Korean, western and Chinese menus at about 20 restaurants and food courts, it certainly would be an appropriate place to organize two or five-thousand couples simultaneously tying the knot.

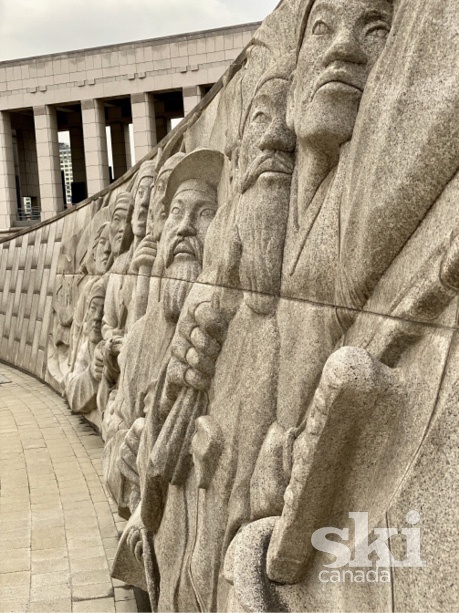

A few minutes down the road from Yongpyong at Alpensia lies a smaller ski area but much bigger resort full of distractions. The facility only opened in 2011 for the 2018 Games and its remaining clean and shiny newness is striking. Ski jumping, biathlon, nordic and sliding events were all centred around Alpensia, and today the Olympic Village is immediately impressive for its high-end accommodations like the five-star Intercontinental and eateries, city-like architecture complete with arresting outdoor art installations, and a busy casino.

Again, not far away, Phoenix Snow Park was host to freestyle and snowboarding events. It was at Phoenix where Adam and I managed to hook up with a young Welshman named Gareth Parry, who was happy to “hike back up and do it again” for our iPhone lenses. Parry’s ski life started with his mum and twin brother, Bryn, on a teenage trip to Jasper and Marmot Basin for a first-ever experience sliding on snow, and he’s never looked back.

“After loving Jasper so much I thought it’d only be right to return to Canada when I was older [18] to try my luck at becoming a ski instructor. I thought, ‘How hard could it be?’” said Parry, laughing. “I’d skied a total of four days in my life and set off to Banff for 12 weeks to learn to ski and instruct. Best decision I ever made. I’m still skiing every day, 11 years later!”

Parry picked up his Level I, then II, and continued life as a ski instructor. “I still rate Lake Louise as one of the best ski resorts I’ve ever been to and worked at,” said Parry. “I don’t think I’d be where I am today if not for the exceptional level of training and skiing that I was able to do there.”

After creating fond memories from $3 Jaeger nights at Hoodoos, an expiring Canadian work visa moved Parry on to Japan with mate Chris. And when the pair was done skiing 21 metres of seasonal snowfall, Chris found a supervising position at Phoenix Park and quickly brought over Parry.

“They also recently had the Winter Olympics here in 2018 so they have a new world-class halfpipe and slopestyle course that I’m extremely excited to ride,” said Parry.

“Culturally, Korea is very different from anything I’ve ever experienced. The ski school is a lot smaller so naturally you spend a lot of time with your co-workers and they become like family since we live, eat, sleep and work together every day. We’ve got free accommodation and canteen food three times a day, which is great: very Korean! (Although I’m not yet the biggest fan of spicy fish and kimchi for breakfast.) The only downside is we have to live in a separate building from the girls, which makes it hard at times.

“They have an unbelievable capacity for snowmaking here,” said Parry. “But if you’re planning on visiting Korea, I would say don’t come solely to ski. Plan a few things like visiting the DMZ or a night out in Seoul, eating, shopping—and skiing. It’s about the experience, with its quirkiness and rules. It’s completely different from other resorts around the world. Also, where else can you ski till 2:00 in the morning?”

We felt like smugglers, arriving in Korea—the land of Samsung—with iPhones in our pockets. Our mission: to shoot an entire magazine feature using only untried iPhone 11 Pros. Remember, there’s nothing spontaneous about ski photography. Take some time to set up your shots and you’re more than halfway there.

Playing catch-up to competitors’ phone cameras, Apple seems to have bounced back into the creative realm quickly and, indeed, is ahead of the pack with its three-lens Super Retina XDR Display version with an endless list of photo and video features. Glowing online reviews abound, and we found:

• Low-light and night photography was exceptional.

• As was portrait mode that allows the user to choose the F stop and depth of focus.

• Details from highlights and shadows on an iPhone 11 Pro just aren’t possible on a DSLR.

• Exceptional editing in-house for the Instagram lot (although it’s easy to overdo it).

• Switching between features like one-touch zoom and auto focus worked well but sometimes challenging for us beginners—and on a cold ski slope.

• Amazingly better battery life!

• No worries about moist environments; with water-resistance up to 30 minutes, the iPhone 11 Pro can be dropped to the bottom of most pools/hot tubs and survive.

• In challenging on-hill, low-light conditions with fast-moving subjects like skiers, remember your phone’s 1-cm diameter lenses are a wee bit smaller than that on a DSLR camera, so you can’t expect comparability. To overcome inherent limitations, set up on the new super-wide-angle mode and have your subject ski almost on top of you while you shoot on Burst mode. (Then, during your edit, sort through the 20 or 30 shots, choose the best, toss the rest—and submit to Ski Canada’s Art Director Norm.)