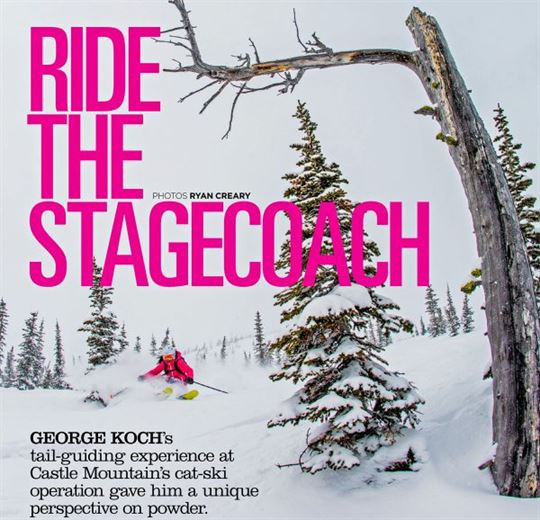

GEORGE KOCH’s tail-guiding experience at Castle Mountain’s cat-ski operation gave him a unique perspective on powder.

in Winter 2017 issue

I discovered some things about myself as a middle-aged skier: I don’t actually mind untangling train wrecks, and there’s intense joy in seeing a complete stranger make his or her first powder turns. For the past two winters I’ve been moonlighting as an occasional tail guide at Castle Mountain’s cat-skiing operation, The Powder Stagecoach. Lean snowfalls and my seasonal sojourns to the Alps have put the emphasis on occasional, but it’s been quite the learning experience and every guiding day was memorable. Swooping down barely tracked slopes of powder lap after lap is as enjoyable as it sounds. But the real reward for me has been helping newcomers overcome their nervousness at skiing off-piste, which helps them to loosen up and start linking turns in ungroomed snow.

The Powder Stagecoach is the only snowcat operation that can efficiently service two groups using a single cat, and because the cat-accessed terrain’s collector trail leads back into the ski area, it’s able to use Castle’s Huckleberry Chairlift for the first part of each ascent. At the top of the chair, guests scramble aboard the cat, and because the road is steep and direct, the ride time is short, the cat wheels around at the top and is back down within 10 minutes for the next group. This built-in efficiency helps explain the low daily price, barely one-third the cost of the highest-end, lodge-based snowcat operations.

The Powder Stagecoach is headed by Darrel Lewko and assisted by Cam Jensen, two highly experienced pro patrollers and avalanche forecasters, and long-time friends of mine. Although the terms “grizzled” and “character” don’t begin to describe the reality, the old curmudgeons take a backseat to nobody in their enthusiasm for skiing. They haven’t lost a teenager’s love of great powder, nor do they fail to get what makes the experience so special for newbies as well as experts for whom powder is still a rare find.

Like many Castle regulars, I had been ski touring up in the lovely rolling terrain below the cliffs of Mount Haig since well before Darrel began the drive to create a resort-based, lift-assisted snowcat-skiing operation. Following its launch in 2007, I became an all-too-frequent guest. A couple of years ago I finally said to Darrel, “You’re embarrassing me with your generosity. I need to earn my keep somehow.” A few months later I was doing pre-season safety training along with about eight other new or returning tail guides.

My part-time warrior colleagues proved an impressive bunch. There was Klaus, a former senior police officer who directed large-scale corporate and event security, including search-and-rescue. Not a bad chap to have around should someone be lost, injured or buried. Brian, an always-smiling ex-Castle pro patroller, now in charge of avalanche control and safety training at one of the huge coal mines operating near Fernie, B.C., which contains long avalanche slopes (not sure how well they ski, though). Dennis, a long-time member of Castle’s board of directors, a professional engineer and backcountry enthusiast who was in the first party to ski the epic beyond-the-ropes backside run known as Six Shooter, and his son Rob, an even better skier than Dennis. And Greg, a ski instructor, custom bootfitter and former pro patroller who’s now the Powder Stagecoach’s reserve head guide, plus several others.

On a bleak mid-December afternoon, we rode the cat up into the terrain and the avalanche rescue scenarios began. We were told the entire slope had ripped out and run full-length, with the lead guide plus an unknown number of guests buried. The other “guests” (fellow trainees) milled about in fear and confusion. The designated trainee had to assess the situation, radio for help and organize the guests for a multi-burial search using avalanche transceivers, followed by rescue/recovery with probes and shovels across a large slope with 200 metres of vertical. The “victims” (buried packs) were up to two metres down. We all felt pretty satisfied when we achieved complete cycle times from the occurrence of the “avalanche” to recovery of the third pack in under seven minutes.

These scenarios were more intense, realistic and large-scale than what I had experienced in my excellent, four-day Avalanche Skills Training (AST) Level II program, the most senior course available to recreational backcountry skiers. The overall experience made me even more interested in developing my formal skills and qualifications, however, so this past fall I enrolled in the Canadian Avalanche Association’s Level I Avalanche Operations professional course.

Having a cat-skiing operation not headed by mountain guides is unusual, and I’m told certain figures in the Association of Canadian Mountain Guides wrinkle their noses at Castle’s arrangement. The fact is, there’s virtually no mountain guiding required. The entire area is just 280 hectares, there’s a rope around it with an obvious groomed collector trail at the bottom, and given Castle’s steep rep, its cat-ski terrain seems almost mellow, and the few real avalanche zones are controlled with explosives and/or ski cutting before any guest goes up—just like in a ski area.

Operationally, the Powder Stagecoach is better described as a limited-access, low-traffic ski area serviced by a snowcat than the true uncontrolled backcountry of a lodge-based snowcat destination. The focus isn’t on delicate route-finding around glacier crevasses or critical decision-making on a complex, 1,800-vertical-metre, multi-pitch descent in poor light and rapidly changing weather. It’s about two things: avalanche control—and here Darrel, Cam and their assistant Tom “Timber” Ross are second to none—and group management.

And that’s where the tail guides come in. Once the lead guide disappears down the fall line (Darrel and, especially, Cam love to ski fast), preventing the group from disintegrating into chaos is 100 per cent on us. The tail guides need to rein in the yahoos while coaxing the trepidatious. We have to impress upon each skier the need to remain within sight of his or her buddy and the rest of the group’s tracks, yet to remain spaced well enough apart not to crash into anyone. Not to veer off at 90 degrees and get lost, yet also not to feel they need to snowboard or ski in old tracks. To take special care to avoid tree wells, yet also not to ride so tentatively that they freeze up and get bogged down. To be safe at all times, yet don’t forget to have fun! And all without sounding heavy-handed, tiresome, irritated (or irritating) or condescending.

Tail-guiding has given me the opportunity to ski with dozens of great, good and not-so good powder riders of all ages and backgrounds from at least half-a-dozen countries. Two especially stood out. One was a gentleman approaching his mid-70s, weighing a hefty 260 pounds. He had eschewed renting fat skis and showed up with little carving skis. He couldn’t ski powder at all. I ended up coaxing him down the mountain one turn at a time, having him ski beside or inside my track, and gently calling out every single move. He could turn one way, but fell virtually every time turning the other way. So, every second turn I’d move just below him, we’d clutch arms and I’d use all my weight and strength to get him upright without having us both go crashing downslope. He endured it all with a smile on his face and, at the end, said, “Thanks, that was great. I just wanted to experience powder once before my skiing days come to an end.”

The other was an athletic, high-cheekboned Slavic beauty who was steadily losing the mental game of coping in an unfamiliar setting. Added to that, her bindings were set too loose and one ski kept popping off. After adjusting her bindings, I began coaching her skiing, having her ski right behind me in some of the tighter spots. She improved visibly with each pitch and soon began linking turns. It was great to see and I really hope the experience didn’t lead her to conclude that the backcountry isn’t for her, but rather that mastery of powder and freeride terrain is within her grasp. She could be on the cusp of a life-long love affair. The Powder Stagecoach gave her, like hundreds of other powder newbies, the option to pursue it. And that’s what snowcat-skiing at Castle Mountain is really all about.