The highest court in the land has given its go-ahead to skiing on Jumbo.

by GEORGE KOCH in the Winter 2018 issue

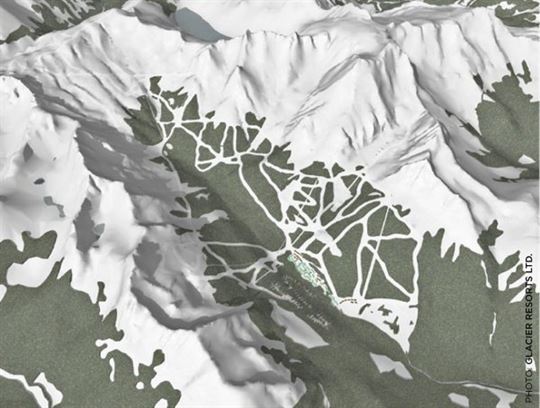

In a sane world, the biggest question surrounding Jumbo Glacier Resort right now would be, “When are they going to upgrade some of these 20-year-old lifts?” After all, the project was green-lighted back in 1993, the gondola onto 3,000-metre-high Glacier Dome opened in 1995 and the resort was since built out to four glaciers and more than 1,800 vertical metres of skiing. Time to renovate!

In reality, Jumbo has spent more than a quarter-century as Western Canada’s most fought-over ski resort. Virtually every permitting step has taken much longer than it should, and passing every bend in the regulatory road has revealed another roadblock. So when the Ktunaxa First Nation in 2013 went to court arguing that the Master Development Agreement (MDA) between the B.C. government and the proponent violated the Ktunaxa’s constitutional right to consultation as well as their freedom of religion, I thought Jumbo had met its end.

The Supreme Court of Canada’s strongly worded 9-0 ruling in early November 2017 denying the Ktunaxa’s appeal came as a stunner for pretty much everyone except, perhaps, the small team at Glacier Resorts Ltd. and its president, Oberto Oberti. The visionary skier who’s been at the centre of all things Jumbo since day one, Oberti is unsurprisingly “delighted” at the ruling and, despite the seemingly steep legal odds, says he was “cautiously optimistic” all along. Now, says the Vancouver-based architect, “Our plans are to move forward, and if the B.C. government were amenable, we could restart resort construction next summer.”

Considering Jumbo’s interminable odyssey, such optimism seems almost mad. Yet it’s probably the very ingredient that kept Oberti plowing ahead. He has accumulated a solid track record elsewhere, including the transformation of Whitetooth ski hill at Golden into Kicking Horse Mountain Resort in the late ’90s, and most recently the remarkably smooth and speedy approval process for a huge new ski area at Valemount. Oberti really should be one of the most beloved and celebrated figures in Canadian skiing. At Jumbo, however, he faced opposition not only from the usual radical environmentalists and NIMBYs but factions in the B.C. government, the Ktunaxa, other ski resorts, prominent competitive skiers, RK Heliski, local businesses like the Kicking Horse coffee company and international giants like Patagonia.

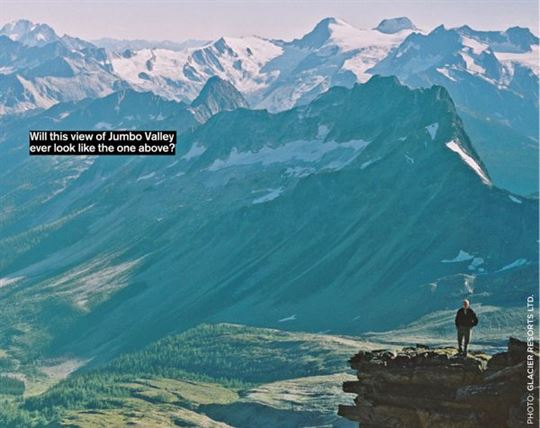

Briefly recapping the tortuous saga is impossible, so here are just a few key items. Claims that the Jumbo Valley, which begins about 18 km west of Panorama Resort near Invermere, is “pristine” and/or prime grizzly habitat have always been false. Much of the valley has been clear-cut logged and studies found it was intermittently visited by just two grizzlies. In the mid-’90s, the NDP-appointed Commission on Resources and the Environment not only concluded that tourism was the valley’s highest value, but its chairman recommended Jumbo proceed without an environmental assessment. Instead, the environmental certificate took nine years to obtain and the B.C. government spent a further five years processing the master plan application.

“There’s been a pattern of injustice in the provincial government’s behaviour toward Glacier Resorts,” says Oberti. “This project has been subjected to continuous equivocations, application of double standards relative to other ski resort areas and industries, and changing of goal posts. While we did the virtually impossible to meet every government request, the bureaucrats played a game of cat-and-mouse to appease the opponents through delay and obstruction.”

Also false were insinuations that all First Nations opposed Jumbo. In fact, the Shuswap—whose reserve at Invermere is the closest of any to Jumbo—recognized the potential economic benefits and signed an impacts management and benefits agreement with Glacier Resorts. The Ktunaxa, whose several reserves are more distant, participated throughout the regulatory process and won multiple changes, including better wildlife protection, ensuring traditional access and a major reduction to the resort’s size. Religious issues seemed peripheral, and neither organization ever claimed aboriginal title to the valley. By 2006, the Ktunaxa’s correspondence with the B.C. government stated the outstanding issues were “funding” and “monies.” The path toward an agreement seemed clear.

But in 2009, a Ktunaxa elder suddenly told B.C.’s minister of lands and forests that five years earlier he’d had a “revelation” that the upper Jumbo Valley—including where the resort village and base area were to be built—was the home of a “Grizzly Bear Spirit” that would be driven from the area forever if there was any site excavation or construction of permanent structures. The revelation’s curiously precise criteria perhaps explained why Grizzly Bear Spirit had managed to survive throughout the previous decades of road-building, clear-cut logging, heli-skiing, summertime recreation and hard-rock mining with a permanent year-round village. But now, the Ktunaxa pronounced the planned resort unacceptable and negotiations over.

The next year, they issued the “Qat’Muk Declaration” asserting the area was of central religious significance and demanding that development be ruled out. In 2012, however, the B.C. government signed the MDA. The Ktunaxa then petitioned the court to declare the MDA issued in error, claiming it violated their right to religious freedom under Section 2(a) of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms plus the constitutional aboriginal right to be consulted over proposed development of any area that could become subject to aboriginal claim. Both the lower court and the B.C. Court of Appeal disagreed. The Ktunaxa were granted leave to appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada, which heard the matter in December 2016.

On November 2, almost a year later, the court ruled. Although reported as a 7-2 decision, all nine justices denied the Ktunaxa’s appeal, with the majority opinion delivered by Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin and two justices departing in some of their reasoning to arrive at the same result. Both opinions went out of their way not to question the sincerity of the Ktunaxa elder’s beliefs nor the religious significance of the Grizzly Bear Spirit. Noting the lengthy time the Ktunaxa had had to state their concerns, the court reminded them (and, by extension, all First Nations) of the extensive case law requiring First Nations to state objections and demands clearly and as early as possible. This was moot, however, because the court also pointedly reminded the Ktunaxa that this case was a judicial review of a government decision, and that the Ktunaxa shouldn’t have attempted to assert a brand-new, never-before-discussed claim “in the guise of” a review.

The majority found that issuing the MDA did not violate the Ktunaxa’s freedom to believe in, practise, proclaim or promulgate their religion. “The Ktunaxa’s claim does not fall within the scope of s. 2(a) because neither the Ktunaxa’s freedom to hold their beliefs nor their freedom to manifest those beliefs is infringed by the Minister’s decision to approve the project,” McLachlin wrote. “The state’s duty is not to protect the object of beliefs or the spiritual focal point of worship, such as Grizzly Bear Spirit.” The Charter does not confer control over lands belonging to others (in this case, the B.C. Crown).

As for the Ktunaxa’s right to consultation, the Supreme Court found this had been exhaustively met. Both opinions agreed consultation isn’t “veto power” and doesn’t “guarantee” that a process won’t go against a First Nation’s wishes. “Granting the Ktunaxa a power to veto development over the land would effectively give them a significant property interest,” wrote Justice Michael Moldaver in the minority opinion. They could then “exclude others from developing land that the public in fact owns,” with the result that “a religious group would therefore be able to regulate the use of a vast expanse of public land so that it conforms to its religious belief.”

All in all, a stunning rebuke of the Ktunaxa’s legal strategy. As Oberti sees it, “The religious issue was the last stand to attempt to arbitrarily deny ‘social licence’ to the project.” Because it sets limits to aboriginal consultation and distinguishes between religious freedom and control of territory (by any religion), the Supreme Court decision may hold equal or even greater significance for contested projects nationwide.

For Jumbo, however, the decision simply leads to more steps. The first will be persuading the B.C. government to okay construction. In mid-2015, using an arbitrary definition of construction, the province’s Liberal environment minister decreed that Glacier Resorts had failed to demonstrate the start of “substantial construction”—which meant that the project’s environmental certificate had, equally arbitrarily, expired. Today, B.C. is run by an NDP-Green coalition whose premier has been a vocal Jumbo opponent.

After that, Oberti has to sort out improved access to the resort site. Realigning the old logging road would be best, but would likely see the Ktunaxa, who quickly declared they don’t “accept” the Supreme Court decision, demand an archaeological study. Upgrading along the current alignment should avoid that, but would require a lot more avalanche control. Then there’s overcoming adamant opposition from RK Heliski. And there’s also the persuasion of investors to commit the approximately $50 million needed for first-phase construction.

Those are just the minimum tasks for Oberti and his key colleagues, son Tommaso and long-time associate Grant Costello. “My feeling is that the project will certainly go ahead and people will enjoy it in due course, but there are technicalities that can be used to delay construction,” says Oberti. I expect all three men will be drawing on their deepest reserves of optimism in the months ahead.