Celebrating BLACKCOMB through the years.

The winter of 1980-81 in Whistler was notable for two events. On December 4, 1980 Blackcomb Mountain opened for the first time. And a month later it shut down after one of the warmest and wettest periods in the resort town’s history.

It was not the auspicious start the provincial government hoped for when in 1978 it put out a call for proposals for a ski resort adjacent to Whistler Mountain. Fortress Mountain Resorts, a partnership between the Federal Business Development Bank (the Business Development Bank of Canada today) and Aspen Skiing Company and the owner of Alberta’s Fortress Mountain ski area, won the bid. As it turned out, 20th Century Fox, the film studio flush off the success of Star Wars, had just bought Aspen Skiing.

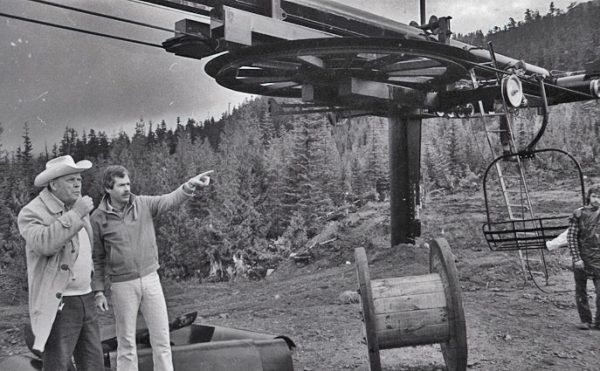

Hugh Smythe, a former mountain manager at Whistler, was the point man for Fortress. It was his job to convince the film studio to invest the $11 million to develop Blackcomb. His pitch: “It doesn’t cost as much as a movie, so you guys should do it.”

Just two years later, lifts started spinning. After “phenomenal skiing for three weeks,” according to Smythe, the rain started on Christmas Eve and was still falling at the end of January. The snow returned in early March and “The Long Run Mountain” reopened.

“I’d have to admit that back in ’78 when we started the planning and working on it, my vision for Blackcomb certainly didn’t come anywhere close to where it’s since grown to be,” Smythe said.

Well, here’s to 40 years of skiing Blackcomb.

| 1978 |

The B.C. provincial government awards the contract to develop Blackcomb Mountain to Fortress Mountain Resorts on October 12, 1978. The target for opening day is December 1, 1980, just over two years away. Blackcomb will be based out of Whistler Village, an under-construction, car-free town centre at the community’s former garbage dump.

| 1979 |

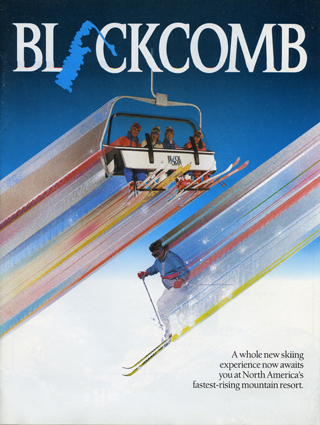

After cutting the ski runs and lift lines from village to alpine during the summer, Blackcomb introduces skiers to the mountain with snowcat skiing. Advertising campaigns promote Blackcomb as the perfect mountain for fall-line skiing with no flats or sidehills.

All photos Whistler Museum

| 1980 |

On December 4 Whistler Mayor Pat Carleton cuts the ribbon, with a chainsaw, to open Blackcomb Mountain. On opening day there are five chairlifts, creatively named 1 through 5, and 1,220 metres of vertical skiing reaching from the village to the edge of the alpine. Even though there was snow to the valley, Chair 1, from the still under construction village, doesn’t run on the first day and skiers fight to find parking into the Base II parking lot. Not much has changed in 40 years.

| 1981 |

Day tickets cost $13, children skied for $5 and a season pass was $300. The 142 hectares of terrain include 33 km of runs, 75 per cent of which is beginner and intermediate. (Today lift ticket costs $149, $75 for kids, and a season pass costs at least $1,000.) There are more than 100 trails in the mountain’s 1,382 hectares, 30 per cent of which is advanced or expert.

| 1982 |

Despite a crippling recession and 20 per-cent-plus interest mortgage rates, Blackcomb invests in its first expansion, adding the Jersey Cream three-person chair. It’s the start of a money-spending rivalry with Whistler Mountain that lasts for 16 years and pushes both resorts to international attention.

| 1985 |

An unused T-bar disappears from Fortress ski hill. Shortly after, a T-bar appears on Blackcomb’s 7th Heaven that allows access to the mountain’s alpine for the first time, including three bowls and Blackcomb Glacier. The addition adds enough vertical to give Blackcomb bragging rights as “North America’s only Mile High Mountain.”

| 1986 |

Intrawest buys Blackcomb Mountain. It’s the first ski resort in the Vancouver real estate company’s portfolio. It won’t be the last.

| 1987 |

The biggest capital expenditure ever adds three new high-speed chairlifts—Wizard, Solar Coaster and 7th Heaven—cutting the ride from the valley to the alpine from 40 minutes to 14. The 7th Heaven T-bar moves to the Horstman Glacier so skiers, winter and summer, can access Blackcomb Glacier without hiking.

| 1987 |

Responding to Whistler’s claim to being the “ski racing mountain,” particularly its Peak to Valley Race, Blackcomb starts its own speed test, the Saudan Couloir Ski Race Extreme, aka “2,500 vertical feet of thigh-burning hell.” It starts on one of the steepest pitches on the mountain.

| 1987 |

For the first time more people ski Blackcomb than Whistler. According to Smythe “It was always competitive with Whistler, but the emphasis on customer service and some of the operational innovations, I would say, was the catalyst that led to so many great things at the resort.”

| 1988 |

Embracing its Dark Side nickname, Blackcomb is the first of the Whistler hills to embrace snowboarders, allowing them on lifts and building a terrain park. First in line is local boy Ross Rebagliati, who will go on to smoke the competition at the 1998 Nagano Olympics and win snowboarding’s inaugural gold medal.

| 1988 |

The Greg Stump ski film Licence to Thrill includes a segment from Blackcomb starring extreme skiers Glen Plake, Scott Schmidt and Mike Hattrup. Footage of them bashing bumps, hucking cliffs and skiing the steeps puts the resort on the bucket list of skiers all over the world.

| 1989 |

Building on its longest ski season in Canada, Blackcomb doubles its summer glacier skiing capacity with the addition of the Showcase T-bar.

| 1991 |

The first-ever boardercross is a collaboration between Blackcomb and FoxTV’s Stump’s World of Extreme. The excitement and carnage of the inaugural four-riders-at-a-time race around banked corners and off big jumps lead to skier adoption and Olympic inclusion.

| 1995 |

Rivalry starts to give way to collaboration between Blackcomb and Whistler. For the first time, we have a choice: a Whistler ticket, a Blackcomb ticket or a dual mountain ticket. Tourists start asking for directions to “Dual Mountain.”

| 1997 |

Recognizing that co-operation is more profitable than competition in the mega-resort business, Intrawest buys Whistler and merges the two ski resorts into Whistler Blackcomb. Hugh Smythe, the president of Blackcomb since its founding, says, “The competition has been fun and exciting to this point, but it’s a different game now. We’re at the point where the landscape is changing very quickly.”

| 2006 |

The New York-based asset management firm Fortress Investment Group (no relation to original co-owner Alberta’s Fortress Mountain) buys Intrawest for $1.8 billion. The purchase includes Whistler Blackcomb and several other ski resorts in Canada, the U.S. and overseas. The coming economic collapse crushes the investment. In August 2009 Fortress tells investors the Intrawest portion of its portfolio is worth $721 million.

| 2008 |

The Peak 2 Peak Gondola connects the alpine of Whistler and Blackcomb in 11 minutes, changing the way people ski the two mountains. The 4.4-km-long tram is an engineering feat that achieves two Guinness World Records: “highest cable car above ground” at 436 metres and “longest unsupported span between towers,” stretching just over three km.

| 2009 |

A run-of-river hydro electric station in the creek between the two hills comes online, powering the ski area’s year-round operations. It follows a long list of efforts to reduce the resort’s footprint that have won it numerous awards for sustainability.

| 2010 |

Blackcomb hosts the bobsleigh, luge and skeleton events during the Vancouver-Whistler Olympics and Paralympics. The sliding centre sits just to the south of Base II and remains a popular attraction.

| 2015 |

A novel snowmaking effort begins on Horstman Glacier in an effort to halt its shrinking problem. The accelerated melt of the snow and ice threatens the summer race training and freestyle camps, and the Horstman T-bar’s infrastructure.

| 2016 |

Vail Resorts buys Whistler Blackcomb for $1.4 billion. “They were persistent and they kept calling and at the end of the day they put a very attractive offer on the table,” says WB’s CEO Dave Brownlie. As a result Whistler Blackcomb joins Vail’s Epic Pass, a multi-area ski ticket program.

| 2017 |

Camp of Champions shuts down after 28 years of running summer freestyle ski and board camps on Horstman Glacier. “Simply put, it’s the effects of global warming,” company owner Ken Achenbach writes to campers. After a dry winter and the failure of the snowmaking program, “I knew that we weren’t going to have enough snow to build the park we’ve been promising everyone all winter.”

| 2018 |

In its first lift expansion in nearly 20 years, the 10-person Blackcomb Gondola replaces the Wizard Express and Solar Coaster chairs. It also realigns Catskinner, one of the oldest lifts on the hill, with a new quad.

| 2020 |

Along with all other North American Vail Resorts, Blackcomb closes on March 15 “temporarily” in an effort to slow the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic. Within days, skiers realize it will be the earliest end of season ever. The rest of the Canadian ski industry soon follows.

| 2020 |

Forty years after opening it, Hugh Smythe is long retired from running Blackcomb but skis most days—on the Dark Side, of course. “Change is always a challenge,” he told the Pique newspaper. “But this is still a phenomenal place to live and work and play. I’d say maybe it’s hidden a little, but if you peel back the layers of the onion, the bones of the resort are still very good.”

Open six days a week, the Whistler Museum is now featuring the avalanche history exhibit “Land of Thundering Snow” curated by the Revelstoke Museum. Photos, videos and artifact donations: archives@whistlermuseum.org