Ruedi Beglinger has made a business out of challenging his guests to push their limits in the alpine.

By ANDREW FINDLAY from Fall 2012

It’s ping-pong-ball visibility on Tumbledown Mountain, but that doesn’t faze our guide. Blue skies, overcast, fog so dense the end of your nose disappears, snow blowing sideways—no matter. Ruedi Beglinger ascends and descends like a machine, carving the same consistent, magazine-perfect turns regardless of what Ullr has in store for us. I suppose it’s the intuitive skill on skis you’d expect from someone who spends 200 days a year guiding guests around his mountain paradise in the Selkirk Range north of Revelstoke known as Selkirk Mountain Experience. We’ve just skinned our way up into the white void to Tumbledown’s knobby summit, a chain of seven skiers barely clinging to the tails of Beglinger’s skis as he climbed with metronomic efficiency.

“Okay, ve take da skinz off here,” he says, and before any of us has clipped out of our bindings, Beglinger has de-skinned and is digging out the summit radio repeater station half-entombed by windblown snow.

No point in dallying on this exposed summit, Beglinger steps back into his skis, buckles down his boots, and with a click of the poles—our cue to follow—he pushes off down a ridge of wind drifts and hard pan into the zero visibility, a line that he has skied hundreds of times before. With elevation drop, the visibility improves and so does the snow quality, though still exhibiting wind effect. Beglinger opens up the throttle, cranking easy turns, seamlessly absorbing the variations in snow consistency. He glides to a stop at the broad saddle of Durrand Pass, and is already applying skins to skis by the time his charges arrive.

“Dat’s not so bad, eh?” he says, with a lyrical Swiss Alps accent that’s as strong as it was the day he first arrived in Canada more than 30 years ago.

Last March I joined him for a week at Durrand Glacier Chalet, the comfortable base for exploring his surrounding 80-sq-km tenure of legendary powder and alpine terrain that defines the Beglinger experience. Beglinger needs no introduction to anyone familiar with ski mountaineering in Canada. Vilified by some—guides in training who have served time at SME and guests alike—for being a short-tempered taskmaster. His exacting Swiss nature manifests in the near plumb vertical walls of hand-shoveled snow that form mid-winter canyon walkways connecting the family mountain residence with the guest chalet and sauna hut. He’s remembered with some notoriety as the guide who bore the tragedy of losing seven skiers, among them guests and snowboarding great Craig Kelly, in that tragic avalanche on La Traviata back in 2003. However, he is also a highly respected guide known for helping guests reach goals in the mountains, ski the sort of lines and bag the kind of vertical they never thought personally possible.

His Durrand Glacier Chalet is equally deserving of renown; a simple but cozy two-storey Swiss-style chalet set on a wooded ridge near the foot of its namesake glacier and surrounded by the kind of ski mountaineering terrain that would be hard to improve on even if you had the god-like abilities to design landscape on a macro scale—long rolling glacier descents, plunging couloirs, steep glades of fir and spruce, high alpine passes, and enough peaks to ascend and ski to keep clients coming back year after year. This is also where Ruedi and wife, Nicoline, an unassuming but attentive host and also accomplished skier and mountaineer, have raised their two sporty daughters, Florina and Charlotte, now both in university. When you come to Durrand Glacier, you are entering Ruedi’s world.

It’s 8:00 a.m.—sharp. Those are the rules—lunches made and packed, beacons beeping, ready to ski and waiting on the heli-pad outside the chalet. Last night we were treated to the cuisine of young Swiss chef Tom Moser, on loan from Le Beaujolais in Banff: roasted sweet potato soup, wild salmon slow cooked to perfection over risotto with balsamico. Dinner was followed by an hour-long roast in the wood-fired sauna, and I went to bed satiated.

Today the sky has lifted, and morning sun blazes through clouds, revealing the voluptuous texture of fresh snow on Tumbledown’s south face. If the weather holds, we’ll traverse over to Mt. Moloch Chalet, the cozy but simple sister to the Durrand chalet, situated at around 2,200 metres in the northeast sector of his sprawling terrain. Food for a couple of days is distributed among our group.

With a click of the poles, Beglinger is off and we fall in, arcing a dozen or so warm-up turns in tricky pie-plated snow through the glades that drop below the chalet to the base of the Durand Glacier and the skin-up spot beneath Goat Peak. With a big day in front of us, the skins are on quickly and we fall in behind Beglinger, who travels across snow with a distinctive gait recognizable from a mile away. Slightly hunched, hips rotating as each alternating ski slides forward, he moves with an almost simian quality, efficient if not aesthetic. Slight in stature but with a wiry strong frame, and an unruly coif of thinning, stringy hair, Beglinger is astonishingly fit for his 58 years, his pace rarely varying whether he’s breaking shin-deep pow or floating atop supportable wind crust. He ski tours far more days than most resort skiers could hope to ski in a season—a million vertical feet annually, Beglinger says. And you know he keeps track.

A few days into this trip, I’m learning the protocol. When he stops and pulls his lunch or water bottle from his pack, which is rare, that is our cue to eat and drink. When he removes skins, we do the same. There is very little coddling on this trip; it’s just not in Beglinger’s nature. For an hour we wind among crevasses and ascend snow ramps, doing end runs around vertical icefalls. Then Beglinger pauses, “Do you vant to check da ice cave?”

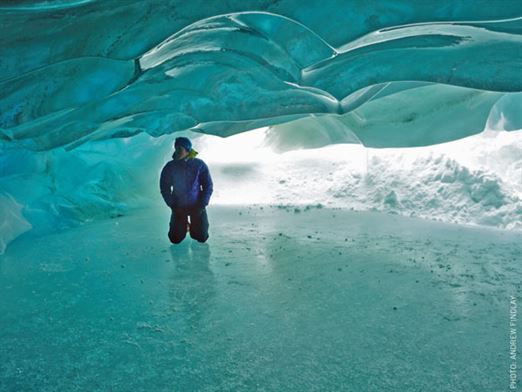

We all nod. If the opportunity for a break presents itself, you seize it. Beglinger heads right, then drops over a small pillow to where a fissure in the snow leads to a massive cavern of ice. We remove our skis, then plunge in thigh-deep snow into this magical cave, adorned with stalactites and stalagmites of ice that could have been sculpted by Gaudi. I recall the photo Beglinger showed me back at the chalet taken of one of his daughters ice skating in the cave—an image that appeared later in a gear catalogue.

In three hours, we have once again tagged the summit of Tumbledown. Clouds press frustratingly upon the Selkirk summits as we ski fast, GS turns in ankle-deep pow down to Durrand Pass. From there we skin up and follow the divide between Diamond and Tumbledown glaciers. Beglinger instructs us to spread apart 25 metres, as we tackle the steep, 40-degree headwall that bars access to the summit of Mt. Ruth. Beglinger forges ahead with his unmistakable simian stride, never altering, never fading. I gaze down Ruth Glacier, mouth watering at the descent that lies ahead. Like most summit dalliances on wind-buffeted peaks, the Mt. Ruth celebration is a brief affair. We drop in, one-by-one, onto the north-facing steep headwall, following Beglinger as he swings east to avoid an icefall then straight down the fall line. The flat light keeps me alert but the snow quality is some of the best so far, shin to knee deep with only the occasional hint of tip-grabbing wind slab.

The 900-metre vertical descent tests our legs and we soon reconvene in an austere valley, dwarfed by the imposing south-facing ramparts of Mt. Moloch. Beglinger flashes a smile, the pleased expression of a guide who has found quality snow in challenging conditions. This spot is called Meeting of the Glaciers, but during Beglinger’s time here the participating glaciers have retreated drastically, leaving behind boulders, rubble and glacial waste.

After lunch, we begin plodding up-valley. I fall in behind Nick Arkle, a forester from Kelowna who’s made at least 10 trips with Selkirk Mountain Experience. “When you come here you really feel like you’ve been invited into a family. It sounds corny, but it’s true,” Arkle says.

Indeed, he’s as close to family as an SME guest can get. After the La Traviata tragedy of 2003, Beglinger asked Arkle to speak at a memorial for the seven avalanche victims. He’s the first to admit that Beglinger has a hard reputation—a man with a driven personality that can be off-putting to some. However, Arkle says that’s why he returns year after year, for the phenomenal terrain and world-class Selkirk powder, but also to be pushed. And it’s a sentiment echoed by two others in our group, among them a couple from Vancouver. The female half, a competitive distance runner, is a first-timer at SME and admits that she trained all season for this week, that the mere thought of skiing with Beglinger was enough to give her butterflies.

Later at Moloch Chalet, I relax with Beglinger after a classic Swiss alpine meal of polenta and vegetables, tasty but as no-nonsense and stoic as the guide who prepared it. The Moloch, situated on an exposed rocky knoll above Dismal Glacier, is the staging point for big alpine ascents of Moloch, Sentinel, Zwilling and other far-flung peaks in Beglinger’s enviably rich tenure. The weather deteriorates, all whistling wind and driving snow. Beglinger shakes his head after listening to a less than stellar forecast on his handheld radio. Plans for tomorrow are in flux.

As we sip red wine, Beglinger talks about his life in the mountains; a topic that was intimately documented in the recent film, A Life Ascending. He was born, raised and certified as a guide in the mountains of Glarus, Switzerland, then came to Canada in 1980 after securing a work visa in his other trade as a tool and die machinist. He landed a job in Winnipeg, and lasted three days before heading west to guide for Canadian Mountain Holidays. He never intended on staying in Canada, but the wildness of the mountains seduced him. In the summer of 1985, after poring over maps and a few helicopter over-flights, he got a lock on his prize tenure north of Revelstoke, determined to introduce a form of guided ski mountaineering that was a step above the woolen-knicker, soft-leather-tele-boot-with-gaiters style that he says dominated the ski-touring scene in North America. At least that’s how he characterizes his multi-decade ski-mountaineering crusade.

“I wanted to show people that ski touring was much more than yurts and snow caves. Back then people were touring with 215-cm telemark skis and leather boots, and they wanted to climb with wax instead of skins,” Beglinger says.

As for his iconoclast reputation as a hard driving taskmaster, Beglinger insists it’s unfounded. Although he guarantees guests 2,000 metres of vertical per day, he has also started marketing what he calls “relaxed pace” weeks. Ruedi-speak for “easy weeks”? Could it be that this legendary Swiss hard man is going soft?

“You know, I don’t like the way the ski media portrays ski touring as an extreme sport. It’s not an extreme sport,” Beglinger says, explaining why he is trying to attract new guests and dispel this image of ski mountaineering as a testosterone-fueled quest to bag 50-degree couloirs.

He takes a small sip of red wine from his ceramic mug. I ask him about “the avalanche.” His face tightens slightly, but he doesn’t shy away from the topic. He tells me not a day goes by that he doesn’t think about the tragedy that put his operation and guiding under a very public microscope, and also caused him to reflect and improve on his practices. Though the sorrow of this loss still burns, he stands by his safety record and that of the industry in general, pointing out that guides like him regularly work in high-risk, uncontrolled environments. A few months earlier a celebrity psychologist and talk show host from New York phoned to interview Beglinger, wanting to know exactly why people choose to venture on skis into this high-risk environment.

“It’s difficult to understand unless you do it. It’s not really about the sport. It’s adventure, playing with the elements of nature and pushing your boundaries in the outdoors. You know, someone should psycho-analyze me, that would be a case,” he says with a laugh, revealing that subtle Swiss sense of humour that makes Beglinger both an endearing and complex character. Clearly he’s a guy who would lose his mind if ever confined to city life, and that’s a quality I can relate to.

The next morning is murky, a ceiling of clouds sitting a few hundred metres above the chalet and lopping off the surrounding peaks. “We have to head back now; big system coming in from the southwest,” Beglinger announces at breakfast, explaining in his direct way why he has decided to bail on plans for alpine ascents around the Moloch in favour of a high-level traverse back to the Durrand Chalet.

It’s a sweet consolation and one of the features that makes Beglinger’s Selkirk Mountain Experience unique, traversing between the two huts through jaw-dropping Selkirk alpine. We switchback steeply up into the mist toward Fang Col. Once we have all crested the ridge, we follow Beglinger as he meanders upwards along a narrow piece of SME terrain that is imprinted on his brain like chromosomes in a strand of DNA. After tagging Mt. Fang, we descend awkwardly, skiing by Braille across the pancake-flat Diamond Platform for two km, then climbing briefly over 2,589-metre Diamond Col.

The sun pokes a hole in the clouds, allowing some welcome reference points—some rock to the right, the wavy texture of the snow in front of us, patches of blue above. On the west side of Diamond Col, the snow is fluffy and forgiving. Beglinger charges ahead with his Swiss-precision slalom turns and we follow. The descent is long and dreamy, as we duck in and out of the fog, winding down the Diamond Glacier. We pause, legs tensed from the effort, at the confluence of the Diamond and Durrand glaciers. Far down, just below treeline, I spot Durrand Glacier Chalet on its sheltered ridge. An inviting trail of smoke puffs from the woodstove; the sauna awaits our arrival.

“My goal is to get people to a nice peak and a nice run,” Beglinger says, as we wait for the rest of the group to join us. “I hope to be doing this into my 80s.”

No doubt he will. For more than 25 years, Beglinger, love him or not, has been delivering the ski-mountaineering goods to skiers from around the world.

The price of freedom

Seven-day ski trips at Selkirk Mountain Experience cost $2,295 per person and includes dining, guiding, accommodation and transportation to and from the lodge from Revelstoke. Group size is limited to between six and eight skiers per guide, and guests will climb an average of 1,700 vertical metres per day. Relaxed pace, steep skiing and avalanche awareness course weeks are also available. www.selkirkexperience.com

HELLY SKIING

I knew before heading off to Selkirk Mountain Experience with a Helly Hansen sample bag to try out for the week that I’d be warm and dry in its baselayers. The heavyweight HH Warm LIFA stay-dry tops and bottoms kept me toasty on those windy sub -10 C days, and the sleek ultra-light HH Warm series was fit for spring-like days.

But what surprised me most was HH’s top-shelf mountain professional series outerwear. The Verglas shell jacket, made with its patented Helly Tech Professional waterproof-breathable fabric, is a versatile performer with a removable zip-out powder skirt, a hood fit for a helmet with one-hand adjustments, and extra-long pitzips to ventilate during long skin-up ascents. The companion Verglas shell pant, though a little on the heavy side in SME’s alpine paradise, is equally up to all the elements of winter mountain conditions.

However, the kicker was sandwiched between the baselayers and outerwear shells—the super-light and super-warm Odin Isolator jacket made from water-repelling PrimaLoft. The mid-layer stuffs down to the size of a softball, and fits snugly in a backpack ready for quick deployment during lunch and snack breaks, or photo shoots on the summit, but light enough

to serve as an insulating layer on extra-cold days or when skiing the lifts. www.hellyhansen.com