Eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow you will ski

We’re under siege and falling fast. This army doesn’t play fair: it’s co-ordinated, exploits our weaknesses shamelessly and knows only victory. And now it’s returning with foie gras—the smart bomb of entrées—the umpteenth of I-lost-count-how-many courses. As it arrives, fantasy and fetish trump common sense: Iain, Leslie, Rosita and I all nod with the same stupefied I-shouldn’t-but-dammit-I-will look. The bow-tied maître d’ senses surrender, extravagantly pouring Château-je-ne-sais-quoi into our glasses. I take a deep breath, shift another belt notch down and pick up my fork once again.

Any way you slice it our situation is impossible. We’ve come for the best of both worlds – to ski and eat in the world’s largest ski area, France’s superlative Trois Vallées. Together, these coveted ski resorts of Courchevel, Méribel and Val Thorens in the Haute Savoie contain some 600 km of interconnected pistes and more skiing than North America’s top-10 ski areas combined. Waistlines be damned; Michelin-starred restaurants lurk at every turn.

COURCHEVEL 1850: FOR THE HIGH AND MIGHTY

The brochures paint Courchevel 1850 as a mythical alpine oasis of mink coats and dazzling food. The lodgings don’t lie: the village, dreamt up while the Vichy Regime was in power during the war, boasts the largest concentration of four-star luxe hotels— France’s highest rating—outside of Paris. And like a fairy tale, the mornings here arise with Cinderella-white peaks and bluebird sky.

After 10 hours of economy flights and a three-hour after-midnight gourmet feast, burning calories comes fi rst on today’s menu. We blast off to the slopes with guide Charles. From the tram’s vantage, Courchevel appears like a two-headed monster. Precision corduroy grooming on endless runs below, and deep-powder backcountry off every side.

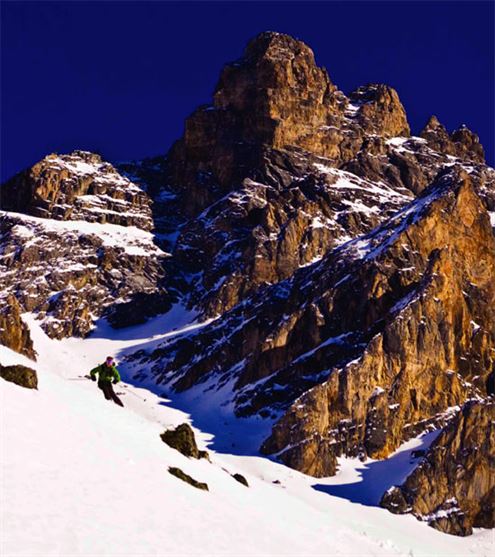

Charles points out La Madame Blanche, Mont Blanc’s dramatic peak in the distance. While we snap pictures of the highest peak in the Alps, he stamps out his cigarette and points to the off-piste area at the foot of the impressive Aiguille du Fruit peak. “Now, ze best skiing of ze free valleys,” he commands in a heavy Savoyard accent. Boots tightened, we race after him under the ropes.

Here we cruise through snow up to our knees in a mountain all to ourselves. Could Charles not be mispronouncing? This sure is starting to feel like the “free-est” of places. We run into local rider and three-time world champion freeskier Manu Gaidet flying off an impossible cliff. We soon spot others. A half-dozen crews are filming for prize money from Columbia clothing in this natural set.

Back in town it seems like impossible is on everyone’s menu. World champion sommelier Enrico Bernado’s restaurant, Il Vino, popped up here after Parisian accolades. Enrico encourages us to play his novel blind-tasting game. At €100 a pop, the mystery dinner comes with four exquisite pairings. Guessing is no small feat—they have one of France’s most extensive wine lists. If anything, our deductions are abysmally off, but the exercise ends with one telling fact. We’re going to have to ski like mad to work this off.

Trois Vallees: 200 lifts, more than 1,500 metres of vertical and a C$260 six-day pass. Mo’ info: www.les3vallees. com or www.franceguide.com

MÉRIBEL: ENGLISH SPOKEN HERE

At the heart of the Three Valleys, the sun warms Méribel’s south-facing terrain all day long. The ski area’s name derives from the Latin Mira Bellum and, as it suggests, boasts fantastic alpine views. As a medal site of the 1992 Albertville Winter Olympics, it also has plenty of infrastructure, including the world record for high-capacity gondolas, making lift lines and waiting out in the cold a thing of the past.

It’s the 25th of January, and not surprisingly, a group of barelegged Scots ski by. Our guide Nadine smiles at the kilts and tells us it’s nothing new. Peter Lindsay, a future British Colonel, erected the first lift in the valley just after the Nazis had annexed Austria in 1938, thus closing off Kitzbühel and St. Anton to the Allies. War delayed construction, but Lindsay and the British legacy returned. Today the village is dominated by Brits staying mostly in chalet group accommodation.

The slope mix here leans toward the intermediate, making it legendary among families. We decide on Méribel’s Big Six pistes. At more than a kilometre of vertical each, these cruise through the high alpine and include various highlights like the 1992 women’s Olympic downhill racecourses— considered the world’s most diffi cult. With aching legs, we decide to take advantage of the warm January sunlight by eating out at the best sun-drenched terraces.

Patio fare in France goes far beyond burgers. Crisp salads, freshly made steak tartar and hand-crafted local sausages get served with fi ne wines at the table. Of all our stops, Allodis stands out. Here a mass of waiters decked out with leathery tans and dark shades rescues us with carts of charcuterie, cheeses, nuts and figs, not to mention a dessert table heavy with crème brûlée, fruit tarts and chocolates under a brilliant sun.

Although planned during the Vichy Regime, the Three Valleys was the waking dream of Laurent Chappis, a World War II prisoner of war who studied architecture at the Université de Captivité. Armed with a 1:50,000 scale map and imaginings of freedom, the avid outdoorsman charted the blueprints for what remains today as the planet’s largest ski area.

VAL THORENS: YOUNG AND YOUNG-AT-HEART

If Courchevel caters to a high-end market and Méribel to Brits in chalets, then the party gang heads to Val Thorens. The highest ski village in Europe, Val Thorens also guarantees great snow and attracts the diehard crowd with its northwest-facing slopes and handful of inbound glaciers. An armada of 2,000 snowmaking guns aimed strategically at its terrain backs the claim. But despite this, much of Val Thorens’ fame comes from the crossing of a diminutive alpine lake, Lac du Lou. Located on a wonderful 10-km descent, that is today’s pilgrimage. And it’s a BYO-PFD affair as locals and foreigners alike try to get enough velocity to cross it on skis. If you don’t have enough speed or stamina to make it, you’re swimming. And with 10 pounds of extra ballast on our waists, we cruise over the cracking, moaning pond ice praying we’ll make it and promising ourselves a diet.

To celebrate the crossing we quickly forget our resolutions and head for Les Aiguilles de Péclet, located in an old log cabin at the top of the gondola. Broad-smiling owner Aurélie Rey walks in with a bottle of wine under her arm and fresh bread in a basket—and then the cheeses, the charcuterie, the potatoes, the warm goat cheese salad, the oeufs brouillés and the foie gras. However, the meal hits its high point when Aurélie brings out her sweet rissoles, a dream of a cream-filled Savoyard doughnut sprinkled generously with chocolate.

To celebrate the crossing we quickly forget our resolutions and head for Les Aiguilles de Péclet, located in an old log cabin at the top of the gondola. Broad-smiling owner Aurélie Rey walks in with a bottle of wine under her arm and fresh bread in a basket—and then the cheeses, the charcuterie, the potatoes, the warm goat cheese salad, the oeufs brouillés and the foie gras. However, the meal hits its high point when Aurélie brings out her sweet rissoles, a dream of a cream-filled Savoyard doughnut sprinkled generously with chocolate.

On the following morning, we wake up to a harsh reality. We have only hours to go before our lift to the Geneva airport. Another run? More food? Or both? I look at Iain, Leslie and Rosita, who are feverishly putting on their skis again. They’ve got those Savoyard doughnuts on their mind. And we fly out the door on borrowed time.

As we race down the slope, a thought comes to me. A week here has made one thing clear: you may have to work for it, but in the Three Valleys you not only can have your cake and eat it, you can ski to it, too.

COURCHEVEL 1850 (www.courchevel.com)

WHERE TO STAY: Alpes Hôtel du Pralong (www.hotelpralong.com) is a five-star, grand slopeside hotel from €1,750 per person per week, including half-board (breakfast and dinner) and a Three Valleys six-day ski pass.

WHERE TO EAT: At Le Chabichou (www.chabichou-courchevel.com) order the six-course sampling menu at €160. Star attractions include the pan-sautéed duck foie gras and the fillet of Limosin lamb—and, in our case, Gordon Ramsay seated next to us. (Two Michelin stars, but 10 in our books.) Il Vino (www.ilvinobyenricobernardo.com) offers a four-course blind-tasting menu (including wines) for €100. Those boasting bigger budgets can go for the one-of-a-kind Wines of Europe menu for €1,000.

MÉRIBEL (www.meribel.net)

WHERE TO STAY: L’Orée du Bois (www.Meribel-oree.com) is a lovely traditional three-star, family-run lodge with a warm lobby and excellent cuisine for €156 per person, per day, including half-board.

WHERE TO EAT: Try the lunchtime special at the Chalet Hotel de L’Adray-Telebar (www.telebar-hotel.com), famous for its veal. For those who prefer more raw experiences, try Le Chardonnet’s unforgettable steak tartar, prepared tableside, with gawking American tourists, at the Pas du Lac midstation. For lunch or dinner, the Allodis (www.hotel allodis.com) offers some of the best dining in Méribel. Its €33 one-course plus desert buffet lunch is the toast of the town, and the dinner tasting menu is to die for.

VAL THORENS (www.valthorens.com)

WHERE TO STAY: The four-star Hôtel Fitz Roy (www.hotelfitzroy.com) is a step above the early Ikea architecture of many neighbours. It offers all the amenities, including ski-in/out, and half-board for €1,890 per person, per week.

WHERE TO EAT: Try L’Oxalys (www.loxalys.com) for its €110 eight-course Le Grand Perron menu that includes chestnut soup, sea scallops and spectacular freshwater char. Les Aiguilles de Péclet (www.lesaiguillesde peclet.fr) is located at 2,945m atop the Funitel de Péclet lift (above Val Thorens). Its lunch menu begins at €15—and don’t leave without savouring the sweet rissoles.