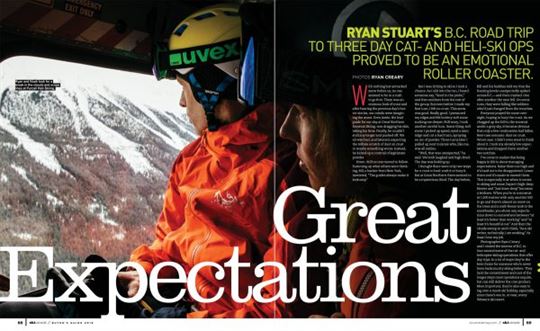

RYAN STUART’s B.C. road trip to three day cat and heli-ski ops proved to be an emotional roller coaster.

photos RYAN CREARY in Buyer’s Guide 2019 issue

With nothing but untracked snow before us, no one seemed to be in a rush to go first. There was an ominous look of crust and after hearing the previous day’s horror stories, our minds were imagining the worst. Even Jamie, the lead guide for our day at Great Northern Snowcat Skiing, was dragging his skis, taking his time. Finally, he couldn’t stall any longer and pushed off. We all watched, and listened, expecting the telltale scratch of dust on crust or maybe something worse. Instead, he kicked up a contrail of legitimate powder.

Hmm. Still no one moved to follow. Summing up what others were thinking, Bill, a banker from New York, muttered, “The guides always make it look easy.”

But I was itching to ski so I took a chance. As I slid into the run, I heard someone say, “Send in the probe,” and then snickers from the rest of the group. But even before I made my first turn, I felt no crust. This snow was good. Really good. I pressured my edges and felt buttery-soft snow sucking me deeper. Still wary, I took another careful turn. Same thing: soft snow. I picked up speed, eyed a mini ridge and cut a hard turn, spraying an arc of powder. Three turns later I pulled up next to Jamie who, like me, was all smiles.

“Well, that was unexpected,” he said. We both laughed and high-fived. The day was looking up.

I thought there were only two ways for a crust to heal: melt it or bury it. But at Great Northern there seemed to be a mysterious third. The day before, Bill and his buddies told me that the freezing levels unexpectedly spiked across B.C.—and then crashed. One after another the men fell. On some runs, they were falling like soldiers who’d just charged from the trenches.

Everyone prayed for snow overnight, hoping to bury the crust. As we chugged up the hill in the snowcat under a grey sky, it became obvious that only a few centimetres had fallen. Best-case scenario: dust on crust. Worst case: I didn’t even want to think about it. I took my already low expectations and dropped them another two notches.

I’ve come to realize that being happy in life is about managing expectations. Raise them too high and it’s hard not to be disappointed. Lower them and it’s easier to exceed them. This is especially true when it comes to skiing and snow. Expect thigh-deep blower and “just knee-deep” becomes a letdown. When you’re in a snowcat at 1,500 metres with only another 500 to go and there’s almost no snow on the trees and a melt-freeze look to the snowbanks, you shove any expectations down to somewhere between “at least it’s better than working” and “at least it’s beautiful out.” And then the clouds swoop in and I think, “As a ski writer, technically, I am working.” At least I love my job.

Photographer Ryan Creary and I visited the interior of B.C. to tour around some of the cat- and helicopter-skiing operations that offer day trips. In a lot of ways they’re the best choice for someone who’s never been backcountry skiing before. They lack the commitment and cost of the longer stays most operations require, but can still deliver the core product. More important, they’re also easy to tag onto a resort ski holiday, especially since there’s one in, or near, every Western ski resort.

GREAT CATS

Not that long ago, the upper mountain of Revelstoke Mountain Resort (RMR) was accessed by cat-skiers and the occasional free-heeled alpine tourer. When resort developers expanded the community ski area, it swallowed a chunk of the cat-ski tenure but kept running the day cat-skiing in its slackcountry. Competition from skiers straying from the resort meant the cat-skiing terrain was often tracked up.

Meanwhile, Great Northern, two hours south of Revy, was a long-running destination cat-ski operation. Skiers came to the lodge for a minimum of three days, but last winter the operation sold to the same group of investors who owns Mt. Norquay Ski Resort in Banff. Just in time for the snow to fly, Great Northern teamed up with RMR to offer day cat-skiing with a shuttle to and from the hill. And the ski resort quietly put its cat to sleep.

Before the sun has risen, day-skiers in Revelstoke can board the shuttle bus that takes them south, across a ferry on Upper Arrow Lake and on to Trout Lake, an old mining town in the middle of the Selkirks. After an avalanche briefing and transceiver training, it’s into the cat and up the mountain. And on the day of our visit, it was into some pretty decent snow.

After those first few tentative turns, the rest of the first run proved to be a mix of nice snow with only a few patches of yesterday’s crust. By our second run, Jamie had the aspect figured out and led us down runs pitch by pitch; he traversed to stay in the sweet zone and cut runs short to avoid the bad stuff. When the clouds lifted, we ventured higher. When they closed in, he changed plans and we dove into the trees.

The terrain was a blast: fun, playful, steep but not intimidating. There were pillow lines everywhere and Jamie set us up for air on almost every run. Only once did we do the same line. At the top Jamie looked at Creary, Noah Maisonette, a talented kid Creary brought along for photos, and me. Then he nodded and dove in. We took it as an invitation and followed his rooster tail, chasing him through open forest with high-speed turns, popping off small airs, trading places and spraying each other. Near the bottom we took turns dropping a two-metre pillow one after the other. Giggling like kids, we called in the rest of the group, leading them into the same perfect drop.

Even last run at the end of the day exceeded our expectations. We popped into a huge old burn, silver skeleton trees rising above us silently, the valley suddenly appearing far below. The burn is huge and Great Northern uses it a lot, especially early in the season. Where the cat would normally collect skiers for après back to the lodge, we kept going, jockeying for position boarder-cross style down the cat road all the way back to the parking lot. What could have been and what I expected it to be, a ho-hum cruise down, turned out to be perfect closure to a great day.

GOLDEN HIGH

The next day of skiing tested our expectations again. From Great Northern we made the trip back to Revelstoke and then over the Selkirk Mountains to Golden for the night. The following morning we headed to Purcell Heli-Skiing’s head office. Again we prayed for snow overnight and again none came. Worse, the cloud line was low. My expectations for the day sank—and then dropped even lower.

At Purcell, Jeff Gertsch, the son of company founder Rudi, was waiting for us. Rudi started Purcell in 1974 after guiding at Canadian Mountain Holidays, the world’s first heli-ski operation. Now in his seventies, Rudi still guides, but Jeff and his wife, Katie, run the business.

As we made ourselves comfortable in the log cabin base, snacking on delicious muffins and apple cider, both homemade, Jeff delivered the bad news. The only good snow was in the alpine, but the cloud layer was too low to fly into the alpine. “We’ll go through the safety briefings and see what the weather does,” he said. “But it’s not looking good.” It suddenly occurred to me that the only thing worse than mediocre skiing was not even going skiing.

As the safety talk continued, the morning darkness turned to grey. The clouds dropped lower and it started to snow. Curiously, in the background I saw guides hauling out skis and changing from jeans to snowpants. Was the cloud layer burning off? I checked the web camera at the top of nearby Kicking Horse Mountain Resort, which revealed bluebird sunny up high.

Not long after that bit of good news, the machine was roaring to life and we took off from Purcell’s heli-pad, right behind the lodge, flying across the valley and following a ridge through the clouds and into the blue. And then we whomp-whomp-whomped our way behind Kicking Horse and up the valley. From a depressing socked-in grey valley, we arrived 10 minutes later in a world of a billion diamonds. The sun sparkled off every snow crystal and the mountains stretched out in every direction.

Jeff pointed out some of Purcell’s tenure, which seemed to extend as far as we could see to the east and south: a labyrinth of glaciated peaks, forested valleys and bowls, cirques and faces of every aspect and length. Where a major resort like Revelstoke has 12.6 sq km of inbounds skiing, Great Northern’s handful of skiers has 75 sq km of powder to play in. Purcell’s share? 2,000.

For the first run, we worked a series of ramps and open faces in the alpine to an opening in the trees, like a natural ski run. The boot-top powder was fast and predictable. We opened up the speed, swooping big fast turns under the blue sky. The helicopter was already waiting for us at the bottom. We quickly loaded skis into the basket and filed onboard. Before I had time to grab a drink and pull out my camera, we were back at the summit.

Purcell is not as high-paced as some operations. Many heli-ski companies shuttle three or four groups around with one helicopter, the bird never shutting down between pickups and landings. “We’ve simplified our operation,” said Jeff. They only run two groups a day. And on our day, near the end of their season, we were the only one.

By our fifth run, the sun was already warm and we were shedding layers. Jeff decided it was time to move so we flew south toward twin alpine bowls protected from the March sun. With low avalanche danger, Jeff green-lighted a cornice drop and we took turns airing into the bowl with mixed results. Then he showed us how it’s done, hucking the biggest and smoothest air of the impressed group.

From there things loosened up even more. We did three more runs in the zone, leaping off the cornice at the top, flying through the midsection at high speed, and popping off little lips and snowed-over trees and rocks. We were relaxed and having fun. It felt more like skiing with buddies than laying out regimented, side-by-side squiggles for a quintessential heli-ski photo.

By two o’clock we’d exhausted our heli-credit. A day of skiing typically includes about six or seven runs, usually about 4,000 metres. It’s often possible to tag on more, for an extra cost, but only at the guide’s discretion. With the rising spring heat, Jeff’s safety-sense was calling it a day. Fifteen minutes later we were sitting on the Purcell lodge deck, stripping layers and eating our lunch.

HAPPY WARRIOR REWARDED

The next morning, we were already back in a dip on the roller coaster of expectations. Our low-hanging clouds had followed us to the Fernie Wilderness Adventures (FWA) lodge, 20 minutes out of town. It was hot and sunny the entire three-hour drive from Golden, but overnight the temperature had dropped and the clouds rolled in, leaving puddles iced over. At the FWA meeting spot, the guides were tight-lipped about the conditions. A map on the wall showed their tenure on a mountain across the valley from Fernie Alpine Resort. I couldn’t help but notice the limited north-facing terrain. On cue, I shoved my expectations about a final powder day to the bottom of my pack and put on my happy-warrior face.

In my early 20s I worked at an outdoor education centre where one of our five mottos to live by was “Be a happy warrior.” In other words, when the going gets shitty, put on a smile and make the best of it. I helped load skis onto the back of the cat and chatted with the guides. Family-owned Fernie Wilderness Adventures is delightfully rustic and friendly, with many of the guides side-hustling their jobs patrolling at the ski resort.

The first run tested my happy-warrior alter ego. We skied over old tracks most of the way down, swinging through the woods to hunt for fresh snow but mostly finding crust. I slumped in my seat on the ride back to the top, but on the second run our guide found the right aspect. The powder was probably a few days old but, like icing on a cake, topped with hoar frost: fast and easy to carve.

With little in the way of true avalanche paths, the guides let us wander in the trees, gathering the group a couple times per run. Creary and I sniffed out untracked lines and took turns cranking turns down the alleys through the conifers. Even at lower elevations and in some sun crust, I actually enjoyed the challenge of figuring out the best way to ski it.

Somehow we spent the day in less than 10 per cent of FWA’s tenure. And we never skied the same run twice. Hidden on the mountain were a lot of micro features and a ton of ski lines. We popped off drops and raced through replanted clear-cuts. We skied an open face littered with ribs and rocks to play on. The pace was “no need to rush” and we often beat the cat down; but like with all cat-ops, we ate lunch on the ride up. And we skied a lot of runs. Where laps are counted in a helicopter, cat-ops focus more on maximizing time in the powder. It was not until 3:45 that the guides called last run.

As we wove our way through trees toward the pickup, I could feel my quads. It had been a long day. I’d lost count of all the runs and I’m more than satisfied with the skiing.

With three turns to the waiting cat, I stopped on top of the last pitch. I can hear the first people pulling up and cracking a beer, celebrating a solid day with a cheer. Like Pavlov’s dog, I started to salivate. I pushed over the edge and the snow billowed up to my knees. I popped into the next turn and felt powder spray onto my chest. I went all out for the last turn and opened wide. Sure enough, snow sprayed right into my mouth.

As I pulled up to the cat, I thought about how I spent months fantasizing about those three days of skiing, dreaming about the deep, untracked fresh, only to be disillusioned by the reality of weather. I had let my expectations get high and then had them squashed. Then, there I was, sitting in the back of a cat drinking a beer I hadn’t expected to have, glowing from a great day of skiing I thought was going to suck, at the end of a trip that looked as if it were going to be a washout.

Great expectations are always trouble.

GREAT NORTHERN SNOWCAT SKIING

Based near the hamlet of Trout Lake in the heart of the Selkirk Mountains, the operation caters to groups staying at the lodge and also day-trips from Revelstoke Mountain Resort. Day-skiing starts at $539. greatnorthernsnowcat.com and revelstokemountainresort.com

Where to stay: Park it at the base of RMR at Sutton Place, the impressive and only on-slope accommodation. Swipe left or right: the shuttle to Great Northern leaves from the lobby and the gondola is right outside the hotel door. suttonplace.com

PURCELL HELI-SKIING

One of the oldest and most respected heli-ski companies in the world, Purcell’s base is a log cabin on the east side of Golden, but the Gertschs also have a heli-pad right at the base of Kicking Horse Mountain Resort. Purcell caters to individuals and groups, for a day or more. purcellheliskiing.com

Where to stay: The Holiday Inn Express is easy to find, just off the Trans-Canada Highway and a quick drive to Kicking Horse Mountain Resort and Purcell’s base. The included breakfast saves making another stop en route. ihg.com

FERNIE WILDERNESS ADVENTURES

In 1995, Kim and Deb Serovic started running day cat-skiing on Morrissey Ridge. Right across the Elk River from Fernie Alpine Resort they have a small lodge at the base and run two cats a day. Guests can stay in town or at the rustic lodge. Day-skiing starts at $400. ferniewildernessadventures.com

Where to stay: In the renovated brick schoolhouse, 901 Fernie is one of the nicest condos in town. It’s located right in historic downtown Fernie, with a plethora of restaurants and shops a short walk away. ferniecentralreservations.com

For more planning information and resources, check out Kootenay Rockies Tourism, kootenayrockies.com.