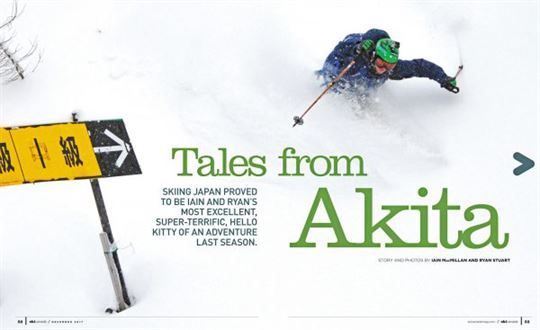

Skiing Japan proved to be Iain and Ryan’s most excellent, super-terrific, Hello Kitty of an adventure last season.

Story and photos by IAIN MACMILLAN and RYAN STUART

IAIN

The conversation stopped momentarily when we suddenly realized what we were looking at through the fog: a massive carved phallus. Although the temperature was well below -10, the colossal woody protruding from the warm waters of the traditional Japanese onsen melted on contact the enormous cakey snowflakes that continued to fall from the heavens. Also, we were totally starkers. And we smelled like rotten eggs.

Curiously, we were the only westerners at the hotel. At least, we thought it was a hotel. There was no actual word “HOTEL” or any western script written anywhere, but there was also no red light hanging near the front door, so I suppose that was a good thing.

The two or three other naked men hanging out didn’t seem to notice Matt as he scrambled about the slippery stones taking photos through the steam like he was late for a Japanese porn-shoot. Meanwhile, Ryan and I tried to find happy spots somewhere between the 80° source of volcanic water and the 2° source of the tempering water. Discussing the day’s turns in this “when in Rome” surreal setting suddenly didn’t seem so odd. With cold beers in our hands and vivid recent memories of skiing nipple-deep powder, it was far more relaxing than I remembered the gang showers of my school days.

It had been snowing non-stop since we arrived in Akita-Tazawako. A virtually windless blizzard almost immediately covered our boot tracks, tire tracks, ski tracks…and those made by our bare feet leading to this bubbling, warm and wet environment. None of us—Matt from England in his mid-20s, me from Toronto in my mid-50s and, in between, Ryan from Vancouver Island—had experienced snow coming down like this.

RYAN

Interesting that Iain started with the giant Japanese wiener towering over the men’s side of the onsen. I must ask him about all those summers spent at a boys-only camp. But at that moment, I couldn’t stop thinking about our turns earlier that day. In fact, I remember thinking after the very first run that I would return home happy—it was everything I had seen and heard about skiing in Japan.

‘‘…while we began wallowing in continuous first tracks, Iain was still scrambling to find a rental ski suit and gloves to match his rental equipment. ’’

What was even more delicious was that while we began wallowing in continuous first tracks, Iain was still scrambling to find a rental ski suit and gloves to match his rental equipment after Aeroflot lost his bags somewhere between Moscow and Tokyo. Flying onwards to Akita City on the northwest coast of Japan’s south island, and then mini-busing it to Tazawako, had ensured a long, ugly separation between Iain and his fat K2s.

It was only earlier that day we had left a sunny, 15° Tokyo and arrived in Akita, the city, to a thermometer reading zero and enough snow in the air to make one cough. By lunchtime, Matt and I were riding the first quad at Tazawako, the largest ski area in the Akita Prefecture.

There wasn’t another person on the lift and only a few skiing under it, most of whom were avoiding the untracked snow that covered nearly all runs. We also gleefully noted that not a sole had laid tracks in the perfectly spaced trees between every piste. I remember wondering if the snow was too heavy to ski or something ominous was preventing it from being trashed. All fears were allayed.

Having grown up skiing Banff, I don’t ever remember snow so light and fluffy. A foot of it blew out of my way like it was down. I danced through the hardwood forest, lazily turning, fluff billowing off my belly.

With no one around to form a line, Matt and I slid onto the lift again, rode the quad back up and then hopped onto the double that headed to the summit of the hill. As we polished off another run of a lifetime right under the chair, I noticed a guy above us on straight skis, in a big-shouldered 1990s outfit, simultaneously singing, whooping and trying to wave at us—or maybe he was about to jump, it was hard to tell.

“Was that Iain?” Matt screamed at me with only mild interest. Gasping in continuous faceshots, I didn’t answer.

IAIN

We were told Japan is home to more than 500 ski areas, with most visiting skiers heading either to the international resorts on the northern island of Hokkaido (just north of our destination) or to the mountains an hour or so west of Tokyo near Nagano, host of the 1998 Olympics. In comparison, Akita is a backwater—a lovely rurally exotic, buried-in-snow backwater.

Akita is a backwater—a lovely rurally exotic, buried-in-snow backwater.

But thanks to Japanese geography, cold Siberian air slams into warm moist Pacific air and stops to unload its burden right over the mountains. The result, we’ve quickly learned, is worth the trip across the Pacific. Next time, though, I won’t bother packing sunglasses.

With six lifts and terrain more akin to a big Quebec resort, it’s not the Coast Mountains, Kootenays or Rockies. At least we’re pretty sure it’s not; it was difficult to see. On each successful ride up, the three of us struggled with FOMO (fear of missing out), pointing in three different directions where we should go next. What we eventually realized, though, was it just didn’t matter. There was so much snow and so much lightness to said snow that tracks filled in while we were riding back up—wiping the slate clean again.

Having made our way from one side of Tazawako to the other, we kept going and discovered that not only did our new routes through the trees end conveniently on the main road, which was carved out like a roofless tunnel two or three metres below the snowbanks, there was also a narrow, thin snowpack on the side of the road. “Just enough slope” to allow us to ski single file becomes “too much slope” at one point, given there was not enough track to check speeds by snowplowing let alone turning. But I for one was on rentals, so the sparks were literally flying with my edges making contact with the geo-heated blacktop as we quickly headed toward the base area and a short walk back up to the main lift to repeat the process again and again.

RYAN

Returning to our still un-named hotel in the evenings, exhausted and wobbly-brained from jet lag, we were at least relieved at not having to think about what to wear to après. Laid out on our beds each evening were slippers and a yukapa, a casual kimono, the jogging suit to the suit. It was standard wear for hall-wandering, dining and evening-entertainment lounging. Iain even had me wear it skiing one day, which brought curious looks from other skiers, especially since we were the only westerners skiing at the entire resort. What we could never get a straight answer to was whether underpants were required. (More of a theoretical question for Iain who was on “critical supply” the entire trip with his luggage never appearing until the return to Canada.)

Roaming about in a robe wasn’t my only unique entry in my skiing Japan notebook, though. None of the ski gear looked anything like what the shops carry on this side of the Pacific. The food both in the cafeteria and traditional dining rooms proved delicious despite every meal involving unidentified potentially edible fare. Bamboo in the breakfast steam trays also grew through the bottomless snow. Sake was served like water. There was an air compressor at the bottom of the hill for blowing snow off your gear. Hot water from underground springs heated steeper sections of roads to minimize the amount of plowing required.

Preparing for a World Cup moguls event the following week, Tazawako had a team of mogul-makers moulding perfectly spaced bumps onto one of the resort’s steepest pitches. With another 40 cm of fresh overnight and a gentle blizzard still blanketing Akita, the five guys working on the closed run were fighting a losing battle. We watched and drooled at the terrain, 95 per cent of which lay untouched.

I suppose it helped that we were so obviously not Japanese, but Matt, Iain and I barely had to challenge the “Closed” designation before the chairlift operator decided we were somehow connected to the World Cup and, like mistakenly getting bumped up to business class, the lift’s loading gate was opened and we boarded the chairlift gleefully. Getting past the last few lift towers required raising our ski tips as we dragged through the untouched snow. At the top, there was no lift attendant. For hours, the three of us had the chairlift and all that it serviced to ourselves. On the first run I watched Iain and Matt ski almost the entire pitch without ever seeing more than their helmets—or the top of Iain’s retro rooster hat anyway.

IAIN

Of course, the routine of lap after lap in light, dry and fluffy Ja-pow eventually required food and water, so after endless runs of snow billowing over our heads, we broke for a late albeit short lunch. After the three of us took turns posing for inappropriate photos involving the high-pressure air hoses intended for pesky flake removal at the lodge entrance, we bounced from busy counter to counter at a mall food-court-like setting. (Vail Resorts Inc. this is not.) At 5’6″, it was easy for me to see the menus overhead, but even better, they came with photos.

The culinary choices reflected the fact that there were only locals at Tazawako. It also made us question our traditional diets as we dove into a whole new gastronomic world of fresh everything that made Canadian sushi and miso soup seem like McDonald’s. Ryan and I are of the body types where suddenly dropping all dairy and bread from one’s diet leads to unasked-for weight loss. On this special trip, where I rarely found something to eat that had actually been cooked, I wondered if there’s a market for a pound-shedding ski holiday.

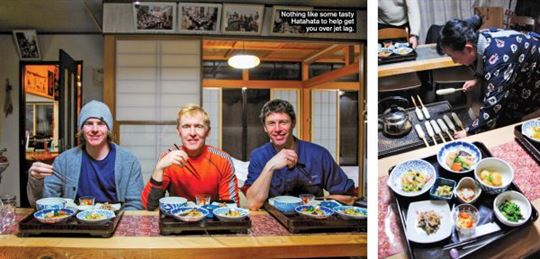

Every meal proved to be a multi-course surprise for the palate. My regular morning müsli was replaced with sticky (very), slimy (yes), powerful smelling and tasting (yikes!) fermented brown bean Nattõ. Young Matt went for tofu—in at least 25 forms. Wonderfully marbled Kobe beef was so tender it could be eaten with no teeth, and the Akita specialty of Hatahata, or sticky god fish, and buriko (its roe) I can safely say I’ve never before tried. Okonomiyaki, sort of a pancake with cabbage and seafood or meat was a keeper. Comparing Japan ramen (with broth, mushrooms, sprouts, pork, seaweed, egg, veggies…) to North American supermarket packages would be like calling Kool-Aid champagne. In Akita Prefecture, the thicker noodle Inaniwa Udon was preferred. Slurping is mandatory.

Often we had no idea what we were eating. Our questions would elicit a lengthy discussion ending with “there is no word for it.”

One night we moved from our labyrinth hotel to a farm stay down in the valley. We slumber-partied six to a Tatami (grassmat-floored) room and helped prepare dinner, learning among other things how to make Kiritanpo, rice on a stick grilled on a wood stove.

But the best meal, in fact the only sushi we ate in Akita, was at a small restaurant in Akita City. Far simpler and fresher than at home, it ended in bucket-list fashion. As former fans of The Simpsons, the three of us enthusiastically recalled an episode where Homer consumes the toxins of improperly prepared deadly fugu, or pufferfish. More lethal than cyanide, our delightful guide, Nayumi, appeared quite entertained when we asked to try it. (Or perhaps she was just tired of us and wanted to go home.) But the chef happily obliged and prepared the tasty treat both in sushi form and also in jellied cubes.

RYAN

Speaking of ways to die, the Japanese paranoia about airborne infection was entertaining. At least that was our first assumption when we saw average citizens walking around with hospital-style surgical masks. It makes some sense on a crowded train, plane or in a shopping mall, but when we spotted a woman wearing one alone in her car and then another on a skier, we became more suspect and asked locals about the practice. But there was no consensus and reasons included: “to humidify the air,” “I didn’t have time to put on make-up” and “it keeps the sun off my face.” I suppose it does prevent nose-picking.

A real threat is the weather. On our last day at Tazawako we had cat-skiing plans. Set up right next to the resort, this service, in its infancy, uses a summer road to climb high onto the ridgeline above the lifts. On Google Earth and in promotional pictures the terrain looked spectacular, with above-treeline ridges and bowls and, below, wide-open trees. Some of it is accessible from the ski area, and a guiding service out of the resort leads touring trips beyond the top lift. In brief windows in the storm, we spotted sweet-looking lines an easy skin from the hill, but since the storm had only intensified since we’d arrived, and with the endless untracked in-bounds, we didn’t venture beyond the open boundary and briefly wished we had instead arrived during a high-pressure spell.

The cat chugged uphill, breaking trail in snow that reached to the top of its tracks. Every now and then it bogged down and had to back up and take a second or third try. Up and up we slowly crawled until the snow got too deep: the cat couldn’t go on. We hopped out into a full-on blizzard, sinking up to our waists with every step.

The ski down (with no guide) was more quirky adventure than epic cat-ski run. Besides the odd pitch, it wasn’t steep enough to venture off the cat track. Instead we flew down and then popped off into the untracked, again sinking up to our waists.

The upside to the failed early-morning cat mission was that we were at the base of the ski area in time for first chair and another day of endless bottomless powder. Our mid-afternoon last run in Ja-pow was sometimes neck-deep and almost always untouched. Reluctantly, we used the air compressor hoses to blow snow off our gear for the last time and headed toward the ocean.

STAYING IN TAZAWAKO

As it turns out, our hotel near Tazawako did have a name and fares were surprisingly reasonable. Staying in a double room at the Plaza Hotel Yamofuso in January and February (the ideal months to ski Japan), with buffet breakfast and multi-course dinner daily and shuttle service to the hill, starts at about C$75 per person.

Start your planning at sanrokusou.com.

Some other helpful sites: akitafan.com/en, city.semboku.akita.jp, acvb.or.jp

TIME IN TOKYO

With a metro population of 38 million, Tokyo offers countless worthy distractions post ski trip. Start your planning at ilovejapan.ca.

Owls Garden: A few yen earns you the chance to pet, hold and hang out in close quarters with a flock of curious owls. And it’s way cooler than petting felines at the Cat Café just around the corner. owls-garden.jp

Transit pass: Buy a pass that includes the expansive subway system and explore the city on your own. Or for more interpretation and local insight, hire a guide like retired Delta Airlines flight attendant Yumi Komatsu, ykomatsuguide@gmail.com.

Emperor’s Palace: The Japanese royal palace is surrounded by a moat and beautiful gardens in the midst of downtown skycrapers. After the war, General McArthur set up shop right across the street.

Shinjuku at night: Once the sun sets, this shopping and entertainment district lights up the sky with neon and giant television screens above the crowds in a spectacle worth experiencing just to contrast with the solitude the sport of skiing brings.

Capsule hotel stay: Slide into your bed (and your room) at a capsule hotel. Just as popular with Japanese businessmen who’ve missed their train home after over-imbibing at karaoke as they are with the younger (and we imagine smaller) international crowd, an assortment of pods (some more posh than others) are available for a unique overnight stay. We preferred the hotel (and location of) Sunroute Plaza Shinjuku.

[Not a valid template]