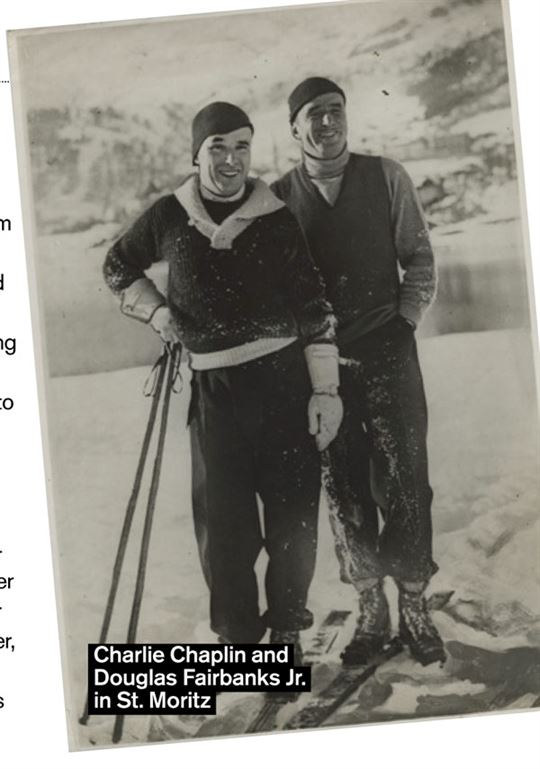

‘Douglas Fairbanks insisted that I be initiated into the art of skiing. I always thought it was easy, but oh, boy! I never knew how many knots I could tie myself into!’

Skiers heading to or from major Swiss resorts of the Valais and beyond will soon have a new sidetrip to distract them. Not far from the imposing Château de Chillon (built in 1150) on the shores of Lake Geneva near Montreaux lies Le Manoir de Ban, the home where Charlie Chaplin spent the final 25 years of his life. A $70-million museum project over 14 hectares dedicated to the Little Tramp opens in the spring, created in part with the help of museographer Yves Durand of Quebec City, who has been working on the project for more than 15 years. Chaplin may be remembered for conquering the hearts of the world and challenging their minds for a social conscience through parody and timeless character, but he also wrote about his skiing escapades in his 1933 book A Comedian Sees The World:

“Douglas Fairbanks insisted that I be initiated into the art of skiing. I always thought it was easy, but oh, boy! I never knew how many knots I could tie myself into! For the first two hours I suffered with impediment of the legs and was continually standing on my own foot. Turning was most difficult, but this I mastered in my own fashion, deliberately sitting down and pivoting in the direction I wished to go. Sometimes, however, the sitting was not deliberate. To a beginner, skiing down a hill is very simple, especially if there are no obstacles in the way. But the problem is stopping. This is most difficult. You are instructed to assume a knock-kneed position, at the same time spread your feet apart and turn your ankles in, digging the sides of your skis into the snow. When I attempted it, I invariably went into the splits.

‘To give you an idea of the enjoyment of my first day’s skiing, you must imagine yourself starting slowly down a hill developing speed as you go, thrilled and exalted with a sense of your own motive power and the icy breezes blowing against your cheeks. As the speed increases, however, your exhilaration changes to a growing anxiety, especially when the hill becomes precipitous and the going increases to about fifty miles an hour. You go flying past rocks, trees and other obstacles that miraculously escape you. After such gymnastic triumphs, you accumulate confidence and go whizzing on, resolved to see it through to the bitter end.

‘Then a sinister rock approaches and comes rushing at you menacingly. This time it is determined to get you. Your heart leaps into your mouth. You become philosophic. You relish the sweet memories of life before skiing. Death is contemplated. You see your skull crashed against the rock and your body flung over it like a pair of empty pants. But you are not killed. You survive. You go on living, crippled for life.

‘Then a miracle happens. Some metaphysical force moves the rock to compassion and lets you skim by it, and you go shooting onward, relieved. Your mind gains control of your reflexes and you make a decision to sit down, not perhaps as gently as you’d wish. So plunk!

“You extricate your head from the snow. You discover you’re still conscious. You involuntarily sit up and look around for fear somebody has seen you. But a superior individual in slow tempo comes gliding up with the query, “Are you hurt?”

‘And you sally with a cheery, “No, not at all, thank you.”

‘Then you endeavour to start off again. But when the stranger’s out of sight, reason becomes the better part of valour, so you change your mind, take off your skis and call it a day.”