We are chivvied off the train at 3:00 a.m., a herd of shrouded refugees hoping to penetrate a hostile border. Bundled in a black coat, I’ve hastily wound a scarf around my head, my hair and my soon-to-be controversial earlobes. It’s not jewel thieves or frostbite I’m worried about. We are about to enter the Islamic Republic of Iran.

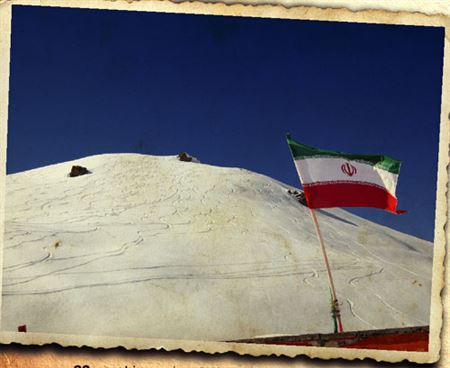

It’s big-mountain skiing in the hulking Alborz Mountains, rising like an icy security fence between the seven- to 12-million people of Tehran and the Caspian Sea. Dizin’s rickety old four-man gondolas climb to 3,600 metres, casting views across Mount Damavand, the 5,610-metre active volcano that’s the highest in Asia. Built by the Shah in the 1950s and ’60s, both Dizin and the neighbouring ski resort of Shemshak were fashionable getaways for wealthy Persians and for the Royal Family themselves. The 1979 revolution changed everything. These days, Allah doesn’t do skiing.

But we do—as do a surprising number of Iranians, backed up by a handful of embassy staffers, practically the only foreigners in the country. After 72 hours on a Graham Greenesque train journey from Istanbul to Tehran—peppered with cameos by security police, agent provocateurs and fellow travellers—we pull in at midnight, greeted by super-sized portraits of glowering ayatollahs. We are two females and a token male, Bob, who quickly and enthusiastically takes on the role of Master of the Harlots; no macho Irani would dream of addressing western infidels such as my friend Lucy and me.

Skis and bags strapped atop a taxi the size of a Thule box, our driver immediately proceeds to get horribly lost among winding mountain roads, turning a one-hour drive into an expedition that culminates in all four of us sleeping in the car till dawn—smack at the foot of the stairs to the hotel we could not locate the previous night.

Come morning, all is forgotten. The surrounding mountains sparkle like tiger’s teeth and our Master negotiates us the two-bedroom royal suite at Hotel Shemshak for $100 a night. Over much-needed coffee for which we paid $30 (complicated currency, rip-off barista), we meet our first locals—two pretty young snowboarders from Tehran. Posing for a photo, the university students insist on removing their headscarves: “The veil is not really us,” one says. “It’s just habit.”

Feeding our habit—powder—was already looking promising. After a 30-minute drive along a hairy one-lane snow tunnel (regularly closed due to avalanches), the snow clouds lift miraculously as we arrive at Dizin. Miles of broad rolling powder bowls, natural gullies and perfect pitches glisten in the sun. Allah has blessed us with 20 cm of fresh feather-light snow and a hillful of ’80s-style skiers yet to discover the joys of the deep. All for us: freeriders from the future.

Of course, freedom has its price. Though none of the khaki-uniformed police patrolling the lift line gives a toss about skiing off-piste, what they do care about is the amorality of my exposed earlobes. “Cover head!” the policeman shouts and waves his fingers at the random man beside me.

“He says you must cover your ears,” explains a slightly embarrassed snowboarder in perfect English. Just down the line, a heavily made-up woman is wearing a flagrant gold lamé Dolce&Gabbana one-piece that’s two sizes too small. “I got it in Dubai,” she told me proudly just moments earlier.

“Who,” I want to ask the policeman, “is the real criminal here?”

The mix of radical conservatism and great skiing is feeling odd indeed. “Our social structure is changing so quickly with more and more liberal teenagers—their music, drugs, alcohol,” explains a 24-year-old IT student from within the discretion of the gondola. “It will continue to change in coming years—then we expect there will be a reaction, a backlash from the government.”

If the on-mountain style is retro, the après ski is surprisingly laissez-faire. Inside the privacy of a local home, we are treated to incredible displays of hospitality. As in any other ski town, off come the headwear and out come the cocktails. And they come, and come, and come. Our new friends, whose names it would be dangerous to mention, feed, water and entertain us to unseen degrees—presumably at some degree of risk of prosecution to themselves.

“There is nothing we can’t get here that you have in the West,” they tell us and, in some cases, prove. From cars and designer goods, to drugs, booze and porn, Iran’s underground economy is alive and trading. “The mountains are the only place we can really feel free,” says one, passing around the keshmesh, home-brewed grappa stored in one-litre plastic water bottles. By her estimation, 70 per cent of the Islamic Republic’s population are drinkers. Indeed, these ones hardly seem to stop.

High above the groomed runs of Shemshak, a series of elegant ridgelines trace a stripe

against the blue sky. Below the rock, great blankets of untracked powder lie just a half-hour bootpack away. From the comfortable lookout of a mid-mountain café, hookah pipe smokers watch the evidently rare spectacle of our small group hiking up, then skiing, the face. Just like anywhere else, we talk it over at après ski—today, in an old stone farmer’s hut where we sit on Persian rugs in front of a fi re, beneath the gaze of a framed photo of the Shah and his fur-collared wife riding the chairlift at Shemshak circa 1959. Our host remembers him as a man of “the people,” queuing with the masses to enjoy his beloved

pastime.

On our final day of skiing back at Dizin, the police are shouting and waving again. Without warning, they have suddenly instituted separate-sex lift lines, making me schlep around to the opposite side of the gondola station solo. A flight attendant from Tehran piles into my bubble amid the last-minute flurry—we are a tangle of skis sticking half in, half out, the old slots being too narrow for today’s wide skis. “It’s confusing to us, too,” she says, laughing it off. “One day it’s normal and all of a sudden it’s changed. It’s Iran.” ?

On our final day of skiing back at Dizin, the police are shouting and waving again. Without warning, they have suddenly instituted separate-sex lift lines, making me schlep around to the opposite side of the gondola station solo. A flight attendant from Tehran piles into my bubble amid the last-minute flurry—we are a tangle of skis sticking half in, half out, the old slots being too narrow for today’s wide skis. “It’s confusing to us, too,” she says, laughing it off. “One day it’s normal and all of a sudden it’s changed. It’s Iran.” ?

SKIING THE WORLD’S HOT SPOTS

GULMARG, KASHMIR

Close to the disputed Pakistan-India border and teeming with machine guns and Indian army commandos, it’s also Himalayan powder heaven. One lift, frequently closed – but it’s the world’s longest that spits you out at just a hair under 4,000m.

THE STANS

Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Afghanistan, You-name- it-stan—they’ve got big bad peaks and even bigger badder guns. Flash enough cash and the helicopter will come a-buzzin’—but don’t come crying if it all goes horribly wrong.

THE CAUCASUS

Don’t let low-intensity civil war in the region put you off: ski touring on Mount Elbrus, Europe’s highest peak, is hallowed ground. Watch this space: Putin has $16-billion plans to build five more Caucasus ski areas. Hegemony, one turn at a time.