Heart of the matter

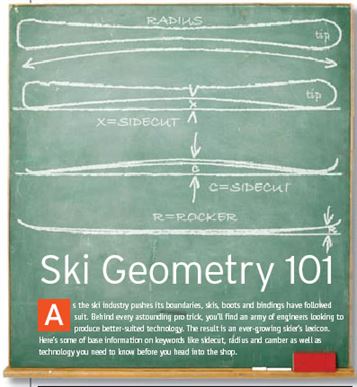

As the ski industry pushes its boundaries, skis, boots and bindings have followed suit. Behind every astounding pro trick, you’ll find an army of engineers looking to produce better-suited technology. The result is an ever-growing skier’s lexicon. Here’s some of base information on keywords like sidecut, radius and camber as well as technology you need to know before you head into the shop.

Sidecut

The concept is simple: construct a skinny waist between a fat tip and tail. When you put the ski on edge, you force its slight hourglass shape onto a flat surface. Presto, a well-curved arc. Years of ski-industry experience has resulted in a couple of general rules: the greater the sidecut (or the narrower the waist width in relation to the tip and tail), the quicker the turn. Rossignol leads FIS’s slalom standings. Its tight and quick-turning Radical RS WC comes in at 114-64-99. The numbers are in millimetres and represent, in order, the width of the tip, waist and tail. Atomic’s World Cup success in giant slalom—with the most points overall last season in both men’s and women’s ski racing—has trickled down to this year’s consumer. Its Double Deck D2 VC 72 comes with a beefier 110.5-72-100.5 sidecut.

These numbers mean something. We initiate turns with the tip of the ski and finish them off with the tail. The narrower the waist, the quicker edge-to-edge transfer between hardpacked turns. However, super-skinny waists—below 63 mm—are skittish. While once as narrow as 60 underfoot, FIS now forbids below 63 in slalom and 65 in giant slalom because of numerous pro-level accidents. (Anyone who has tried walking on stiletto heels will tell you that a wider footbed offers more stability.)

The widening trend can be seen in just about all the ski lines, like the reshaping of last year’s Völkl all-mountain Tierra for women from 118-76-104 to today’s 129-78-99. And bigger isn’t only better in the backcountry, it’s a necessity. Big-mountain skiers need increased surface area to keep afloat (skinny boards, while great on hardpack, submarine in the pow). The fattest cats in the snowbank this season are more than 150 mm underfoot— that’s the width of some waterskis!

Radius

When modelled in computers, the sidecut triad produces another sales-counter statistic: radius. Engineers compute the flexed ski edge as part of a circle to determine the ski’s turning radius. Rossignol’s aforementioned Radical RS WC snaps a crisp 13.2-metre radius. Its beefy backcountry brother, the Phantom Pro RC112 (140-112-120) has a sluggish 35 metres. Remember, it’s not meant to be a carving board, thus 35 metres is just fine for its application.

Most men’s skis fall somewhere in between. For example, the aforementioned Atomic D2 VC 72 is 16.5 metres. Women’s boards can be even quicker-turning, like Völkl’s all-mountain Tierra with its 12.3 radius. Keep in mind that the radius is computer garble that generalizes turnability and shape. Ultimately, it’s up to the ability of the skier to manage the ski.

Fischer’s lineup is fairly typical of the divisions found in the ski shops: men’s High- Performance and All-Mountain boards range between 12- to 17-metre radii. Fischer’s Big- Mountain products tend to be north of 20 metres, with the Watea 114 at 27 metres. If speed is your only concern, think straight, skinny and flat. World Cup downhill skis are up around 50 metres.

If you want to keep it simple, focus on the waist, the middle number. Looking for frontside, edge-to-edge samurai precision? Think 74 mm or less underfoot. Frontside to all-mountain type? Stick to the mid-70s to high-80s. Snow surfing only? Expand your waist to triple digits. Most of the 11 models in K2’s Backside series for instance are wider than 90mm, the DarkSide is a portly 128 underfoot and the Pontoon is a corpulent 130!

Camber and Rocker

Camber is an arching system. Lay a ski down onto a flat surface and if the midpoint is raised, you have camber. When counterflexed (or stepped on) in a turn, this arch strives to snap the ski back into its original state. When the pressure is released, it rebounds, making it lively (or dull if the ski is old), crucial in frontside carvers. Traditionally, when camber wore out, it was time to go shopping.

But camber has never been necessary for big-mountain skiers. In fact, the conventional downward arch has made staying afloat difficult because it can help a ski to dive into the snowpack. Enter rocker design, which starts the tip rise near the midpoint of the

ski. Numerous technologies exist. For example, Völkl’s Extended Low Profi le (ELP) design promises to give skiers the benefits of a long, gradual bend for big snow skiing, yet still offers easy manoeuvrability onslope.

The four-part system is based on: (1) providing a rounded overall shape to allow steering and speed control without sacrificing tracking characteristics; (2) three flex zones going from stiffest in the front (remember, the camber is reversed so the tip doesn’t have to be softened) to a soft tail, which allows easy turning; (3) specific sidecut commensurate with ski shape and intended audience; and (4) a lower tip shape, which means that the peak of the tip is as high as it is on a regular ski, just that it rises more slowly to get there. This results in a smooth ride on groomed slopes while offering increased lift in deeper snow. Some skis also offer rocker in the tail for playing with mountain features.

A zero camber ski is just what it sounds like—there is no camber, it’s flat. This is a compromise for those looking for an All- Mountain ski good in both big snow and in the frontside, but specific to neither.

Does length matter?

While short skis turn faster, they also vibrate more. Longer skis offer more snow contact, resulting in more control. And control is the key to safe skiing. No surprise then that this year skis are getting longer and fatter. If we compare the ski industry to the housing market, it’s like we are leaving the minimalist studio apartment once and for all. And with more square footage below, you can expect more bells and whistles—and a lot less vibration.

What is reverse sidecut?

Just when you thought you understood it all, there’s also reverse sidecut. 4FRNT’s brand-new, lion-emblazed CRJ (designed by pro skier CR Johnson) is a soon-to -be classic of the genre. Skis with reverse sidecut look like the Popsicle sticks of yore, with a pair of near symmetric bulbous heads connected by regular camber through the waist. The widest parts of the board are moved centrally in from the tip and tail to reduce tail drag and hooking in powder. The ski arcs normally between these contact points on groomers. However, the reverse sidecut (where it thins out near the tip and tail) and rocker on both tip and tail make it an ideal board for getting atop the snow and highlighting the mountain’s features.