The International Snow Science Workshop brought the world to Banff to help make us safer in the backcountry.

by KEVIN HJERTAAS from December 2014 issue

You’re standing atop an impressive mountain face blanketed in sparkling powder. It’s the kind of run that keeps you awake autumn nights visualizing each and every turn. It’s also the type of slope that could easily produce a fatal avalanche. So here you stand with a decision: “Is this the day to ski it?” How do you decide?

At a conference in Banff in early October, 800 avalanche professionals were having the same daydream. The International Snow Science Workshop (ISSW) hosted a who’s who from every snow-related field. There were engineers with PhDs discussing snow’s porosity and tortuosity (don’t worry, we all had to look it up, too). Social scientists were discussing new decision-making models and how exactly people deal with risk. Ski guides were sharing case studies from times it all went wrong. Explosives manufacturers had booths alongside avalanche rescue gear companies. It was an impressive collaboration of anyone with anything “avalanchey” to share.

Held every two years in snowy spots around the planet, 2014 marked the return of the ISSW to Banff, where it started back in 1976. Surely five days spent with the biggest brains in snow will better equip me to deal with that decision point next time I find a dream line like yours. Maybe one of these scientists will create a futuristic laser gun that we can point toward a slope and know with certainty whether or not it will slide (cool sound affects included).

So I spent the week listening to presentations, reading papers and talking snow over beers while hunting for at least a metaphorical laser gun.

I followed ski guide Geoff Osler to the daily panel discussions, with topics such as “Avalanche safety equipment for ice and alpine climbing” and “Compaction: Does it work?” Instead of a presenter on stage, these discussions were a chance for peers to share opinions. According to Osler, “That format is fairly new and as a practitioner, the panels are super relevant. You have five people discussing things so it’s a good range on every topic and the audience always had input.”

Alex Sinickas sat on the panel of a controversial topic, “What has science done for us?” and did a great job bridging the gap between researchers and those working in the mountains by pointing out how ski patrols routinely employ the scientific method of Question, Hypothesis, Experimentation and Analysis—all while skiing powder on a good day. “Patrollers carry notepads. They make bets on the chairlift. They like to throw bombs. And they really like to talk about it later,” said Sinickas.

You can’t actually deny science has improved our safety in the mountains. Advances in rescue equipment and methodology have been obvious; quicker transceivers, more effective shovelling and better communications all increase the chance of surviving an avalanche. Social scientists have helped make public avalanche bulletins more clear, concise and better formatted for decision-making.

The next step might be smartphone apps that streamline all the available information and help you make field decisions in real time. Beta versions of a few GPS-based apps were on display in Banff. One even navigates you down the mountain while avoiding areas deemed too dangerous for the conditions. These apps link to current avalanche bulletins and weather reports to help the novice understand what’s going on, but there was palpable discomfort from many of the avalanche forecasters at the conference. Some were not comfortable with the idea of their bulletins feeding a device that made actual decisions for people. It’s safe to say the uncertainty of avalanche forecasting has experts shying away from clear “go/no-go” decision-making tools and leaning more toward experienced decision-makers.

Along with smartphones, experts are looking at ways to use social media tools. Bruce Tremper of the Utah Avalanche Center talked about how much the Center’s public forecasting team learns from recreational skiers coming home every night and posting videos or trip reports. Limited observations while forecasting vast areas is a major problem when writing avalanche bulletins. The more observations you can get, from experts or amateurs, the better. Especially in data-sparse regions like the North Rockies, where Grant Helgeson is looking at new techniques including crowdsourcing and social media to get more information.

On the pure research side of things, Scott “Dr. Snowflake” Thumlert presented a science paper with a lot of big words I won’t tax you with. More than just a large brain, though, Thumlert skis hard and gets after it in the backcountry, so I asked him why he hasn’t developed the avalanche laser gun yet: “We are dealing with a very complex mountain environment with a medium [snow] that is near its melting point and constantly changing, thus the theories haven’t been developed to a point where they can be applied without much judgment by the practitioner.” In other words, we shouldn’t hold our breath.

After a week at the ISSW, I know a bit more about the avalanche phenomenon. I saw how different operations around the world deal with it. I tried to soak in the experience of others while listening to their stories. I heard the word “uncertainty” 100 times (beer is the only word that tops that actually). I learned that science presentations sound better with a Swiss accent. And I learned that science moves in incremental steps. The avalanche laser gun we want is still a long way into the future. The only way to make your decision atop that dream run easier is to get more education and as much experience as possible. Those turns will be worth it!

Digital digs

The Avatech SP1 is a brand-new tool that measures snowpack structure, slope angle and aspect in seconds, then allows you to geo-tag it and share with colleagues or other users. Ski guide Geoff Osler likes the idea: “It’s a cool concept that could change the way we gather info.”

Digging snow profiles or “pits” is time consuming and gives you a look at just one small location on a much bigger mountain. Ideally, you’d have many points of data from all over the area you’re concerned with and that’s where the SP1 probe might change things. At US$2,249 it’s not likely a tool for backcountry skiers, but it could be a tool of the future for professional operations like ski hills and heli-skiing operations who can use it to get lots of information about layers in the snow quickly. The SP1 takes over 5,000 measurements per second, and in the time it would take you to dig one profile by hand, you could check a layer of concern in 15 different spots across a slope. Check it out at avatech.com.

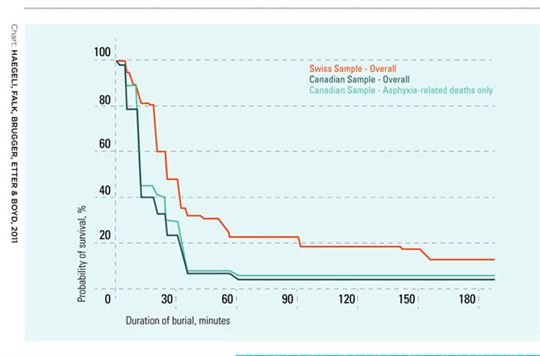

What are your chances of surviving an avalanche burial?

Survival rates for avalanche victims vary slightly for different mountain ranges around the world, likely due to differences in typical snow depths, terrain and snow density. We can look at burial times and make some generalizations, though. First off, speed is of the essence! If you can get a victim out in under 10 minutes, his chance of survival is better than 80 per cent. After that it continues to drop rapidly, so take the time to practice companion rescue often and make sure the rest of your group does the same. On the other end of the curve, there appears to be a five to 20 per cent chance of survival even for those buried two hours or more since hypothermia slows down the body and decreases the oxygen needed.