“This is a little weird, isn’t it?”

It’s End-of-Season party night at the Mica Heliskiing lodge and Claire Challen, the visiting host for Ski Television on Sportsnet, is eyeing the revelry. Everyone’s in full costume, Claire herself pulling off a billowy red cat suit and beach-ball-sized curly black wig.

But it’s the staff who are crushing guests in the part-eh effort. Normally office-bound ladies boasting official titles are shakin’ it on the floor, and atop the big bar another staffer is doing her best Miley and having some guests wondering about happy endings. New Guy, the neophyte ski shop tech hired from another heli op, is rockin’ his pasted-on tiger tights and black bra over bare chest, hoping to earn a month of employment for each successive ensemble he puts on.

My reverie is interrupted by bellows of “Shot Ski.” The bar-gal straps mini-glass ski boots into the mini-bindings mounted to an old wooden ski, and with guests and staff swaying as one mass, I step up along with three fellow idiots to lift the board and have liquor hurled down our throats in unison.

by George Koch from Fall 2014 issue

“Oi’ve nivah ’eard of ‘Bruces’!”

Our fire-engine-red A-Star B2 had just lifted off from the breezy ridgetop and we were strapping up our Snowpulse avy packs for another lap of “Golden.” I was skiing with Herb Marcher, a friendly commercial helicopter pilot originally from Graz, Austria, but latterly from Alaska and Spain, and Melbournites Mal Hart and Mark Foley. We were guided by Rob Turner, fondly remembered from my last visit to Mica eight years distant.

The hoped-for overnight snowfall hadn’t quite materialized, the morning bringing tricky cloud banks, so we had eased up the Molson drainage (where, yes, runs are named after beers). The valley’s scenery was even more arresting than I remembered, huge cliff walls pushing skyward on the north side and every now and then southward glimpses across the Wood River to some miles-wide, thousands-foot-high crags. Mica lies in the true Rocky Mountains, not the Purcells, Selkirks or Monashees, and it felt very good to be back.

About 60 per cent of each run’s vertical that day was good- to great-quality powder, the remaining 40 an energy-sapping April ratatouille of varying consistencies. But game faces remained on in our competitive group. My new-found mates seemed indestructible, with Herb confessing in his charming Austrian-accented German that he was a former ski instructor, while Mark and Mal said they trained for heli-skiing by running in soft sand with sand-filled backpacks.

Beyond not spending all their free time chugging Foster’s, Mark and Mal violated another Australian stereotype in being oblivious to Monty Python’s “Bruces” sketch. Typically Aussies will threaten to punch my lights out at the mention of the old English satirical troupe’s infamous creation, but Mark and Mal wanted to hear it. Their guffaws and cackles rang out through the trees as I yelled out the rulebook from the University of Woolloomooloo: “Rule 4: Now this term, I don’t wanna catch anybody not drinkin’!” plus lines that are simply not PC nowadays.

The runs here tended to the narrow, too tight for a Bell 212’s skier-load, pointing to Mica’s continuing foremost advantage: its all-small-group format. Typically only four groups of four guests will share two A-Stars, with a third machine sometimes added for a private group. Our last pickup had been typical: pilot Don “Badger” Noltner swooped into a tiny clearing like Gandalf himself, his more than 57,000 heli pickups on display as he flared smoothly with his tail boom just clearing trees. The small-group format allows near-instant turnarounds, making for big-vertical days when conditions allow. “You know we skied 21,000 vertical metres in our first two days here and we weren’t even staying out late,” Mal commented. “We needed a day off to recovah.”

This day’s winner was Golden, a 700-vertical-metre smoothie spilling off a ridge down a broad bowl, rolling into a steeper slidepath, then running out for more than a kilometre of slope, judging by the tiny speck that Rob became. Golden was well-named: silky the whole way, but not a pushover. The supple opening bowl hurtled by in a rush of 15-metre plumes. I yawed over the roll before sinking down, pulling outside-ski g-forces on the face, with the run-out screaming at all of us to open up into huge turns. A bit like pulling a long draft into the biggest stein in the bar—then being dared to down it non-stop. We did four great laps in Golden plus several other pleasing flavours. After 8,250 vertical metres, my legs felt like acid-lava-fire and the homeward flight was welcome.

“Like great sailing ships with towering masts and enormous keels, mountains are alive at their tallest peaks, humming in the elements, alive at hearts of stone floating on the fiery matrix which gave them birth. Perched on mountains, I am a human speck of an observer to this wild extravagance of creative force.”

—Andrea Mead Lawrence,

“A Practice of Mountains”

Back at Mica’s beyond-merely-spectacular new lodge, my eyes were drawn to a 1915 wall map of the first formal reconnaissance along the Columbia River’s 300-km Big Bend stretch from Donald (north of Golden) to Revelstoke (from where one gets to Mica today). Whole areas remained white or unknown. A few mountaintops were flagged as “points well located,” with entire ranges listed as “9,000-10,000” feet high, vaguely outlined glaciers, plus a peak, Mt. Chapman, perhaps reflecting cartographer Robert Chapman’s vanity. A window into a lost world—barely 100 years ago.

I sat down with a gin and tonic, gazing west across the Kinbasket Reservoir far below the lodge, at the Monashees’ seemingly endless north-south march. To the left, just beyond the now-submerged Big Bend’s apex, stood the northernmost Selkirk mountain like an angry black bellow. Also submerged lay a Fur Trade-era boating encampment, where explorer David Thompson passed after his walk through the Rockies and on his way to being the first white man to trace the Columbia’s complete path to the Pacific.

The map encompasses what would become much of Canada’s classic heli-skiing terrain, harbouring numerous operators from Great Canadian to CMH, plus Chatter Creek abutting Mica’s enormous tenure to the south. This coming winter happens to be heli-skiing’s 50th anniversary, Hans Gmoser having offered his first commercial ski week in spring 1965—for $275!

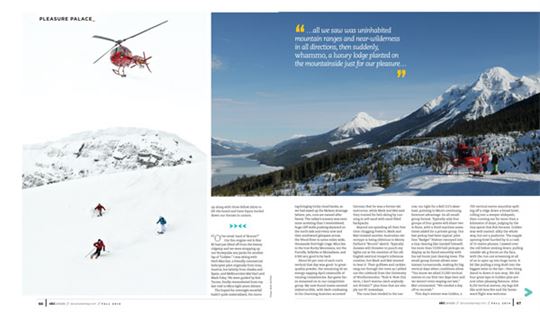

Mica, which started in 2003, is still one of the remotest areas a skier will ever see—more than seemingly isolated places like Bella Coola. Mica lies amidst a huge area without permanent roads, no permanent settlements for probably 200 km along the lake. Flying in across the lake from the shuttle drop-off, all we saw was uninhabited mountain ranges and near-wilderness in all directions, then suddenly, whammo, a luxury lodge planted on the mountainside just for our pleasure, the helicopter landing just metres from the building and entertaining those who’d already arrived as it buzzed in and out.

The new lodge eschews ski-country log-house tradition for a design that’s current and chic, equal parts 21st-century estate home and metropolitan boutique hotel. It’s dominated by huge areas of glass, tile, stone and even concrete, with swank furniture throughout. Practical, too, with each guest assigned a large gear locker with boot-drying tubes, a cubby and drawer, and a leather bench for donning boots running alongside. Rooms have 12-foot ceilings and ample-sized beds with cushy duvets and plenty of pillows—high-end everything, including stone-inlaid shower floors. There’s good Wi-Fi but with so many spectacular days, bandwidth is limited to discourage frenzied GoPro uploading. The 1:1 staff to guest ratio means one is pampered with everything from equipment-repair help to fresh-baked cookies.

After I’d filled my plate with après-ski soup, smoked meat and cheese, goody-laden nachos and quesadillas, Mica operations manager Barb Rose showed me the original paintings and photography by regional artists adorning the lodge walls. Many show Canada’s long Group of Seven influence, others are stylistically unique. All are interesting in their interpretations of the mountain landscape, including some by Ski Canada contributing photographer Mike McPhee. One of the nicest is Natalie Harris’s understated chiaroscuro depiction of a rolling slope with four powder tracks. My personal favourite was Stephanie Gauvin’s brilliantly colourful imagining of the old Mica lodge set beneath a mystical white mountain, looking more like an Alps farmstead circa 1800 than Canada.

Memorable dining is a must-have for high-end heli and snowcat operations. Each of our dinners was a three-course extravaganza of soup or salad with main courses like pork tenderloin, roast chicken with polenta or an incredible rare and tender lamb sirloin. Dessert was always to die for, the highlight being bread pudding topped with a mocha ice cream.

With guests being stuffed by all this great food, evenings could have become sleepy affairs of low murmuring—were it not for The Vikings! Alf, Rune, Nils and Are were almost walking Norwegian stereotypes: more-than-merely hard-drinking, chain-smoking and earthy, yet highly educated, one a software developer and the rest senior engineers in Norway’s high-tech offshore oil industry.

Most guests and staff, plus the two Ski TV party animals, would disappear early—but not the fearsome descendants of Amundsen and Nansen. They’d head for the bar, defining their own last call. One or two would torment the bartender with corny puns and wheezy laughs. The rest would argue over whether atoms genuinely consist of matter or merely interlinked forces creating the illusion of mass. Without warning, Are yelled, “What year was the fire in the Great Library of Alexandria, Egypt?” (Hint: it happened more than once.) He then forced me to google Ulvik, a village in Norwegian fjordland where his summer home lies.

Early the next morning, The Vikings strolled in and were appalled at the staff’s refusal to mix up a round of breakfast Bloody Marys, nipping from their own flasks instead. But I would learn they skied all day and never quit. Guide Erik Ostropkevich described them as “hardy folk”; I simply nicknamed them Ragnar, Floki, Rollo and Bjorn after the characters in the TV show Vikings.

“It’s cold outside

But there’s fire in your eyes”

—Kenny Wayne Shepherd

It’s at once magical, formidable and humbling to heli-ski in the true Rockies, just a few miles west of the Continental Divide and Jasper National Park. In good weather Mica’s guests can view—perhaps the only time in their lives—some of the Rockies’ iconic peaks from a little-known angle, while skiing among unforgettable mountains and glaciers.

It’s serious terrain with an often-tricky snowpack, so avalanche safety is always a priority. Everyone’s visit begins with some solid training in avalanche rescue going far beyond a mere recitation of don’ts. In a small-group operation so distant from roads, towns, hospitals and other operators, the guests themselves will need to be useful in a rescue situation.

Everyone wears the Snowpulse/Mammut avalanche bag backpack and carries a proper VHF radio. Besides holding a shovel and probe, there’s room for an extra clothing layer plus a few sundries. The packs have rigid backs for some protection in a serious tumble. The various straps and Mica’s fast turnarounds do trigger some scrambling at the landings so I found the best routine was to arm and strap up the pack first.

One day found us exploring the Dawson drainage with guiding manager Shane Kroeger. I was surrounded by high-end skiers: Izzy Lynch, a sponsored rider and (she proved) ardent pillow-dropper, Ski TV videographer Darryl Palmer, Fernie-based photographer Mike McPhee and Claire, herself a Level III race coach and former downhill racer.

Yukon Jack was the day’s clear winner, opening with several short rolling pitches before coming to the heart of the matter: a tree-studded, boulder-dappled ramp careering into a leftward-curving avalanche path. Darryl and Mike set up below and prepared to roll vid.

Claire descended joyfully, a shimmering Welsh beauty moving masterfully from edge to edge and cranking around features, leaping pillows with an occasional yelp and arcing magnificent long turns as her mind perhaps flashed back to the 135 km/h days. The word “passion” has degenerated miles beyond cliché. But that concept doesn’t even begin to describe Claire’s connection to skiing. From watching and talking to her it became evident she has a near-mystical relationship with the very idea of skiing—and every second on her edges is golden. It showed.

Shane was equally impressive, taking the most aggressive line beginning with a solid six-metre entry drop leading him over a series of pillows and into deep arcs, with two eye-opening-sized sluffs shooting past him as he arced his big exit turn.

For me it was exhilarating to be pushed beyond my standard cushy powder effort. The snow was just a shade off blower and a metre-deep in places, and the descent was a blurred whoosh of pillows, tree aversions, deep extended speed-scrubbing turns, spine-lined straight shots and a bit of sluff mismanagement as I was briefly knocked off my feet but not out of the game by some snow that had the temerity to catch me from behind.

Good skiing weather, alas, proved in short supply. Spring is like that. “If we had high-pressure air with cold nights and clear days, we’d be flying half an hour to our farthest terrain, landing above 3,000 metres and skiing 1,000-vertical-metre north-facing glaciers and some juicy south-facing corn, and racking up big vertical,” commented Rob ruefully back in the lodge. Then there’s the other kind of April: humidity and shifting convection with clouds at high, middle and low levels. The goal is to land high enough for dry snow—but still below the cloud ceiling—and pick up low enough to make a decent-length run, but not so low that half the run is schmoo. It makes the guides’ job tough. It means that late-season guests need to suck it up, ski smart for the snow conditions that are underfoot (not in their heads), and remain aware of hazards as small as bogging down in heavy snow and tweaking a knee.

Our nadir came on the third morning. The overnight freezing level having shot above 2,000 metres, we’d be skiing in the alpine or not at all. Thick cloud lay everywhere, so the latter looked more likely. As the groups shuttled out, the ceiling dropped further, landing zones were befogged and the rain set in.

“This’ll take all my race-coaching muscle memory just to get down,” muttered Claire before bounding off without a care. I followed with hoots of “Yee-haw!” and “Steep ’n’ deep.” Still, the forced levity couldn’t erase the gathering gloom, for there was only one more skiing day ahead and the forecast was again iffy. No wonder that night’s partying was raucous.

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

—T.S. Eliot, “Little Gidding”

We stand beneath monumental black spires on a broad endless slope, facing hanging glaciers ready to push off enormous seracs. Sunlight sparkles off uncountable freshly fallen crystals. Following the depths of the recent bad weather—as well as what, for me, had been my most limited and tortuous overall ski season in decades—I felt as if I’d come out a grinder of perseverance, hope, deliverance and, at last, redemption. Grandiose thoughts, perhaps even pompous, but it felt to me like eternal human themes playing out on a small, happy scale here in the Rockies’ splendour.

There was one other skier who perhaps was experiencing something similar. Yolanda, from Edmonton, had struggled on her first-ever heli-skiing sojourn and only second time in powder, overwhelmed by the combination of tight trees, challenging slopes, variable snow and meagre light. But she had stuck it out, and this morning she, too, was out with us, Mica providing a personal guide for her to ski at her own pace and boost her confidence. Several runs into the morning, as we flew in over the pair of them, there was Yolanda making smooth linked turns in the morning sunshine, a smile on her face. The rest of us landed again beneath the vaulting hound’s tooth spire off Dunkirk Peak and, unending room to left and right, descended through a golden world of joyful and effortless turns.

Getting to Mica

Location: Guests rendezvous at Mica offices in Revelstoke and shuttle about 150 km to Mica Dam, then fly 20 km to the lodge above the east shore of Kinbasket Lake. Kelowna airport is a 2.5-hour drive; Calgary International Airport is 5 hours, but Rogers Pass on Hwy 1 frequently closes in winter.

Packages: Low-season 3-day, $6,390 per person; high-season 5-day, $11,750 per person. Taxes, alcoholic beverages and gratuities not included. All packages include ground transfer from Kelowna; private packages include heli-transfer from Kelowna directly to the lodge.

More info: www.micaheli.com