The crew at Fernie Alpine Resort is super pro, but they still have a blast bombing around the mountain.

BY PAT LYNCH Photos HENRY GEORGI in the Buyer’s Guide 2017 issue

The sun has yet to rise over the Elk Valley in southeastern B.C. and Kevin Giffin is holding court in the Lost Boys Café, a low-lit post-and-beam restaurant towering some 700 metres above the village of Fernie Alpine Resort. At 47, the mop-topped director of Fernie’s ski patrol commands the room with a lighthearted touch. It is St. Paddy’s Day after all, and judging by what we can all see outside the windows, it’s shaping up to be a pretty straightforward one for the 42 full-time members of his patrol, many of whom are gathered here at the top of the Timber Chair for the morning meeting.

It feels like late-season—lots of hard corduroy on the groomed runs, the promise of blue sky and trees that have long-since dumped their loads of snow.

We know this much about what the day will hold: overnight the temperature dropped to -7.5; it’s expected to reach a high of -1 this afternoon with scattered cloud. Three cm of fresh snow with a total water equivalent of 2.6 mm fell through the darkness on this mild March night, bringing the total snow height to 330 cm. Winds will be light, from the west. The sun will rise at 7:50 a.m.

Data is crucial as Giffin starts handing out assignments to his crew, dividing up the team between the two sides of the mountain: Timber or Lizard. The first priority on a day like this is running trail checks, where the patrol spreads out individually skiing every run on the hill, checking grooming conditions, winch anchors and off-piste terrain.

Hazards must be marked or reduced. Decisions on what terrain can be opened must be made. And the clock is ticking: The dispatchers who disseminate info to the general public need to know what’s going to be open by 8:45 a.m. in order to accommodate the demands of the crowds lining up for first lift at 9:00.

The patrollers gather up their gear and start making their way out of Lost Boys. Giffin leaves them with a final thought and a wide grin: “Remember, safety is no accident. Oh, also: Don’t fuck this up!”

————

Avalanche control has forever been part of Fernie’s patrol history. When Robin Siggers (61) first arrived here from the Lower Mainland in 1977, he started as a ski instructor; two years later, after an avalanche wiped out the newly constructed Griz Chair, the hill was mandated to increase its patrol size and install an avalanche safety department that would oversee the resurrection of the Griz. Siggers got on that crew and has been working at Fernie ever since, either as a patrol member, avalanche worker or in his current role as operations manager of the entire facility.

Back then, Siggers was part of a crew of four who were responsible for avalanche control. They used fewer explosives than they do today (but still bombed the Lizard and Cedar bowls with an Avalauncher) and spent more time ski-cutting slopes that they’d largely have to access by skinning uphill. But the ever-present danger of a slide has never faded away. With steep terrain, lots of snow (upward of 1,300 cm per year) and five bowls that funnel into the exact same place, Fernie’s patrol is required to do avalanche control on 60 to 80 days out of an average 130-day season.

Accidents can happen: In the lead-up to opening day 2000, an inbounds avalanche buried an employee. Siggers was one of the first on the scene to assist in the search and rescue. “There was an early season instability in the snowpack that was causing more problems so it required more checking, more work, and one of our lift operators, on his break, strayed into an area that had yet to be controlled,” Siggers says. Confronted by two uphill patrollers, the lift operator admitted to not having an avalanche beacon on moments before the slope released and swallowed him under a metre of snow.

Siggers raced to the lift near where the slide had happened and radioed for his dog to be rushed to the scene. “I’m riding the lift and I know how long the lift takes and what the odds are. And I know the person in there. It was pretty terrifying.”

Ten to 15 minutes had passed since he got the call. As Siggers hopped off the lift, a snowmobile arrived with Keno, his yellow Lab, and they joined the rescue. Keno found the shallow-buried staffer and pulled off his glove. The liftee was semi-conscious but came around quickly after being freed from the slide and getting oxygen on-site.

“He was fine; he actually came back to the resort like an hour after we shipped him out to the hospital. It was a terrifying experience, it turned out well, but if it’d gone the other way…”

According to the Canadian Avalanche Rescue Dog Association, that was the first live rescue by a trained avalanche dog recorded in Canada.

Recent technological advances have made avalanche prediction more of a science. Much of the same data that Siggers and Co. were collecting in the ’70s is still collected now—snowpack, weather and snow profiles—but digitization of those data has allowed for easier retrieval and storage of information as well as the ability to analyze and overlay years of data to better predict snow stability. Fernie’s snow safety director and chief forecaster, Mark Vesely, has been behind much of that technological evolution. Still, at the end of the day, snow control decisions require boots on the ground.

“When it comes right down to forecasting avalanches, you have to know how to filter that massive amount of information to determine what’s important on any given day,” says Siggers. “You’re still primarily looking out the window and trying to figure out, based on observation, what’s going to happen and what’s the most important thing to look out for today. That hasn’t changed all that much.”

The biggest shift in avy forecasting, according to Siggers, has been an increased attention to how people make decisions under pressure or when fatigued. “Risk management has advanced. And understanding human decision-making and things that can affect your decisions—biases like the pressure to open terrain. I used to always say that if I opened all the terrain that people wanted, they’d be dead.”

That pressure to open terrain is something Giffin has dealt with directly. He remembers locals giving Fernie patrol a hard time just 10 years ago. Instead of “Legendary Powder,” people were calling the hill “Legendary Closures.” At the bar in town, people would finger-in-the-chest complain to patrollers.

“We’re lucky. We’ve never had any fatalities from avalanches in Fernie, which is, I think, something to be really proud of,” says Giffin. “But I mean, that should be our standard as well. We shouldn’t be opening terrain if people are going to die in avalanches.”

————

An hour after the lifts are open and the public has begun making its way up the mountain, we’re gathered in the patrol hut at the top of the Bear Chair. The walls are covered in clipboards detailing this morning’s snow conditions and possible hazards all over the mountain. Radios crackle as members of the patrol call in details from the slopes—dangerously frozen berms, missing signs or ropes, icy patches—all of which are tracked by Vesely and the patrol forecasters who update the charts with weather and snow info, helping to build a detailed profile of the conditions that will be fed into a historical profile.

Outside the hut, one of Giffin’s patrol is chatting up the public as they unload from the Bear Chair. The patrol will spend a couple hours each morning greeting skiers at the top of the Whitepass or Bear chairs. It’s a service for the guests, but it’s also a way that Fernie’s patrol has reshaped its presence.

Managing the public—and its expectations—is an ongoing job for the patrol. Since those days when Giffin would get harassed at the bar over keeping terrain closed, they’ve implemented systems that keep skiers skiing, even when a lot of terrain has to remain closed. Nowadays, the patrol tries to get every chair on the hill open straightaway, but still manages terrain access through the use of colour-coded sign lines that indicate whether certain areas are open or closed to the public.

“When we started using ‘sign lines’ six or seven years ago, that’s when things really started to change,” says Giffin. “People weren’t standing at the base in the rain listening to the bombs going off on top and wondering what’s going on. You’re limiting where they can go, but we can move people up the mountain quicker and, in their eyes, there’s a lot of terrain open.”

By noon, if patrol’s not getting swamped by skiers in need of assistance (a magic hour when gear begins to malfunction, people get tired or make mistakes and need first aid or a snowmobile ride back down the hill), they’ll typically turn their attention to event setup, where they help third-party event staff and cat crews move gear, mark jumps, set up gates—whatever needs to be done to make the event happen. And events happen at Fernie pretty much every single weekend.

As the day wears on, responsibilities often shift from maintenance to first aid. And, predictably, the majority of accidents happen while the crew is making a concerted effort to get everyone back to the top of the mountain for the final hill sweep of the day.

“Usually in that last hour we get a couple of wrecks, which deplete our overall numbers up top,” says Giffin. “And if something happens after 3:30, then those patrollers aren’t going to make it up for sweep.”

When they’re all finally in place and the call to sweep begins, the day’s still not over. “You start running into people who are stuck, tired, injured, lost, whatever,” says Giffin. “Some days there’s nothing and some days it’s all of the above. It’s a vicious cycle…” He pauses and laughs. “You’re kind of always just waiting for something bad to happen.”

————

By Giffin’s estimate, the 42 members of his Fernie patrol have, combined, hundreds of years of experience under their collective belt. In an avalanche area that Siggers jokingly refers to as a “target-rich environment,” that’s probably a fair estimate, considering the Fernie patrol likely sees more large avalanches in one season than many patrollers will see in a lifetime.

The amount of work that the Fernie crew does seasonally quickly moves the green, Level I Canadian Ski Patrol members up through the ranks, experience-wise. Though the unwritten rule at the hill keeps newbies working as assistant avalanche control technicians until at least their second year, Giffin says they could earn their blasting ticket (which requires six “missions” and 25 hand-thrown explosives) in two shifts at Fernie, where, on a big-snow day, the crew could huck upward of a couple hundred charges as part of their avalanche control duties. Over a typical season, Fernie goes through 4,000 kg of explosives and runs an average of 20 heli-bombing missions. Everyone learns from the more experienced members of the crew who do the actual blasting and who are constantly expected to be teaching.

“I’ve always had the attitude that everybody does everything,” says Siggers. “Nobody’s at a position where they can’t do a job because it’s beneath them. Humility in this business is a key element—if you think you’re better or smarter than somebody, then nature is going to kick you down pretty fast and show you that you’re the same as everybody else.”

Humble though Siggers might be, the numbers don’t lie about the Fernie crew: out of 42 members, 25 have Canadian Avalanche Association Level II certification. Four more have gone through Level III. When the CAA was creating the hard-to-come-by Level III certification, it recruited 10 patrollers from across B.C.—three of them came from Fernie. They’re pros, but they can still have a good time.

“We’re all pretty tight friends and I think you need that,” says Giffin. “You’ve got a lot of Type A personalities who are working in a high-stress environment and sometimes things will get heated. But you have to have fun or no one would be able to do it. You’ve gotta drink a beer at the end of the day with the crew, you’ve gotta hang out and tell your story. And you’ve gotta listen to the other ones.”

Guns

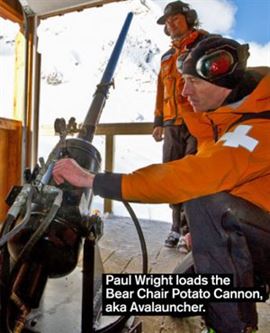

“Well, it’s better than skiing around throwing shots,” jokes Paul Wright, an 18-year Fernie patrol veteran as he loads the Avalauncher near the top of the Bear Chair.

Powered by nitrogen, the pneumatic cannon is used whenever there’s been at least 10 cm of snow, and allows patrol to blast the Griz Face from a comfortable distance, getting conditions in the Cedar Bowl into safer condition. With help from an assistant patroller, Wright counts down the launch and with a pop, fires a bomb into the distant headwall. The shot, aimed at rocks to trigger a more powerful slide (an explosive sunk into the snow is less effective), nails its mark and releases a cascade of powder that spills down to the cat-track beneath the Griz Face.

The guns are actually the byproduct of old baseball throwing machines, says Wright. “Back in the day they’d light a stick of dynamite and fire it out. Obviously that’s not the safest idea.” He reloads the gun and fires another perfect shot.

Bombs

Ever since the Winter Olympics came to Vancouver in 2010, it’s been trickier for patrol to get explosives up the mountain to the avalanche guns. The international attention put pressure on the province to ramp up safety across the board. For the past two seasons, Fernie crew has no longer been able to store significant amounts of explosive in a magazine near the Bear Chair gun.

“We used to be able to have 500 kilograms of explosives in the gun tower and now we can have 25 kilos overnight,” says Kevin Giffin, Fernie ski patrol’s director. Proximity to the public was the worry, regardless of a track record that told a different story.

Logistically, that means when there’s snow on the way to Fernie, patrol can’t stock up on explosives for the next day until the hill has been closed to the public. So, when the forecast calls for snow, the bombs start making their way to the mountaintop at around 4:30 p.m. on the back of a snowmobile.

Fernie is one of several resorts offering transceiver training areas.

Dogs

There are five four-legged members of the Fernie patrol—part furry ambassador, part crucial element of the search-and-rescue team. All are members of the Canadian Avalanche Rescue Dog Association, an organization affiliated with the RCMP that assists the provincial emergency program.

“We’re part of a community group as well,” says Robin Siggers, Fernie’s operations manager. “So we’ll respond to avalanche rescues anywhere in our area—but it’s a good thing to have here at the resort for both inbounds and nearby out-of-bounds incidents that do occur…slackcountry, stuff like that. They’re not just people’s pets, they’re working dogs—the training is all standardized and there’s annual certification.”

Fernie’s five are enough to keep two dogs on patrol daily (one for each side of the mountain) and a spare pooch left to chew on a bone while she waits for her moment in the snow.

GEAR

When it comes to getting geared up at Fernie, the patrol’s needs are professional: the kind of outerwear that performs in harsh conditions, has all the bells and whistles, but still looks great (and performs) during après ski. To that end, the Fernie crew (along with all mountain professionals working at Resorts of the Canadian Rockies) has turned to Helly Hansen for their official gear for more than 10 years. Eventually the technology in this gear shows up in what we wear—and here’s what they’ve been wearing lately:

Patrol Jacket

Half-tool, half-outfit, the Patrol Jacket was designed in collaboration with mountain safety and rescue professionals—hence the interior radio and goggle pockets.

Patrol Pant

With venting in all the right places, the Patrol pant is perfect for pros who need to skin or hike to hard-to-reach places. Equipped with knee pads and a notebook pocket.

Patrol Vest

If MacGyver were on patrol, this would be his vest of choice. This high-performance sleeveless has pockets for medical devices, a radio harness and utility webbing to hold pens, carabiners and that lift ticket wire doohickey thingy.

Regulate Midlayer Jacket

Use it for stand-alone wind protection or zip it into a Helly Hansen shell—the Regulate jacket uses H2Flow technology to customize the insulation level to the conditions.

Dry Baselayer

With 40 years in the game, this is the original HH baselayer collection. The long-sleeve is all about moisture management and quick-dry, extremely breathable insulation made of the company’s stay-dry technology.