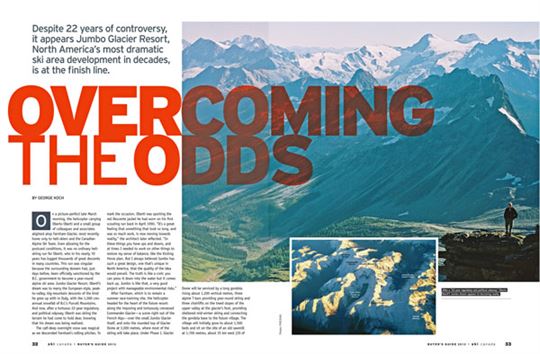

Despite 22 years of controversy, it appears Jumbo Glacier Resort, North America’s most dramatic ski area development in decades, is at the finish line.

BY GEORGE KOCH

On a picture-perfect late March morning, the helicopter carrying Oberto Oberti and a small group of colleagues and associates alighted atop Farnham Glacier, most recently home only to heli-skiers and the Canadian Alpine Ski Team. Even allowing for the postcard conditions, it was no ordinary heli-skiing run for Oberti, who in his nearly 70 years has logged thousands of great descents in many countries. This run was singular because the surrounding domain had, just days before, been officially sanctioned by the B.C. government to become a year-round alpine ski area: Jumbo Glacier Resort. Oberti’s dream was to marry the European-style, peak-to-valley, big-mountain descents of the kind he grew up with in Italy, with the 1,000 cm+ annual snowfall of B.C.’s Purcell Mountains. And now, after a tortuous 22-year regulatory and political odyssey, Oberti was skiing the terrain he had come to hold dear, knowing that his dream was being realized.

The calf-deep overnight snow was magical as we descended Farnham’s rolling pitches. To mark the occasion, Oberti was sporting the red Descente jacket he had worn on his first scouting run back in April 1990. “It’s a great feeling that something that took so long, and was so much work, is now moving towards reality,” the architect later reflected. “In these things you have ups and downs, and at times I needed to work on other things to restore my sense of balance, like the Kicking Horse plan. But I always believed Jumbo has such a great design, one that’s unique in North America, that the quality of the idea would prevail. The truth is like a cork: you can press it down into the water but it comes back up. Jumbo is like that, a very good project with manageable environmental risks.”

The calf-deep overnight snow was magical as we descended Farnham’s rolling pitches. To mark the occasion, Oberti was sporting the red Descente jacket he had worn on his first scouting run back in April 1990. “It’s a great feeling that something that took so long, and was so much work, is now moving towards reality,” the architect later reflected. “In these things you have ups and downs, and at times I needed to work on other things to restore my sense of balance, like the Kicking Horse plan. But I always believed Jumbo has such a great design, one that’s unique in North America, that the quality of the idea would prevail. The truth is like a cork: you can press it down into the water but it comes back up. Jumbo is like that, a very good project with manageable environmental risks.”

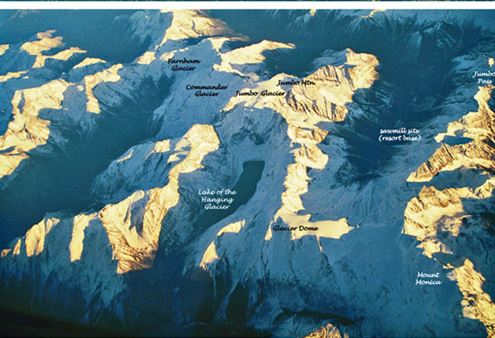

After Farnham, which is to remain a summer race-training site, the helicopter headed for the heart of the future resort: along the imposing and tortuously crevassed Commander Glacier—a scene right out of the French Alps—over the small Jumbo Glacier itself, and onto the rounded top of Glacier Dome at 3,000 metres, where most of the skiing will take place. Under Phase I, Glacier Dome will be serviced by a long gondola rising about 1,200 vertical metres, three alpine T-bars providing year-round skiing and three chairlifts on the treed slopes of the upper valley at the glacier’s foot, providing sheltered mid-winter skiing and connecting the gondola base to the future village. The village will initially grow to about 1,500 beds and sit on the site of an old sawmill at 1,700 metres, about 35 km west (20 of which are paved and plowed, the remainder being logging roads needing upgrading) of Panorama Resort near Invermere.

From our perch atop Glacier Dome we could see nearly all of the future Phase I resort, although the weather was turning blustery. The announcement a week earlier by the Liberal government of B.C. Premier Christy Clark that it had approved the Master Development Agreement for Jumbo was, by Oberti’s count, the seventh crucial step in the Jumbo saga. The previous six were his original signature of an Interim Agreement with the B.C. government in 1993, approval by the East Kootenay CORE Table in 1994, the provincial Environmental Assessment Certifi cate in 2004, approval of the resort’s Master Plan in 2007, the Impact Management and Benefi t Agreement with the Shuswap First Nation (which has its reserve at Invermere) in 2008 and the 2009 reconfi rmation of the 1996 vote by the Regional District of East Kootenay (RDEK) requesting that the province form a Mountain Resort Municipality to govern the resort, instead of controlling it via local zoning.

Those were just the turning points. The process included almost innumerable studies, reports, disputes, reversals, negotiations, declarations and agreements. Although Oberti fulfi lled every demand, he says, “A lot of focus was placed on how a possible approval would resonate politically, while our view was that the process should focus on the design and whether it was acceptable from an environmental, aesthetic and engineering standpoint.” But politics did dominate—which made the March 2012 announcement all the more surprising, coming from a government in rocky political shape. I was told through separate channels that Bill Bennett, the East Kootenay MLA who has been a vocal Jumbo supporter despite frequent attacks, brought the matter before cabinet over the winter and pushed his colleagues to make a decision.

To say Oberti has the patience of Job fails to illuminate the nature of his journey. Over the 22 years, premiers, prime ministers and presidents have come and gone, ruling parties have been voted out of offi ce, wars have been fought, huge skiing corporations have risen and gone bankrupt, the world economy has boomed and lurched through repeated crises—but Oberti has endured. For many people, quietly giving up would have seemed more rational. Then again, Oberti never dreamt it would take 22 years.

“For a long time, Jumbo was “next year country”, he recalls with a chuckle. “Following the Interim Agreement, we continually anticipated approval ‘next year’. Our understanding was always that once we fulfilled the officially required steps, approval would occur in accordance with the law and policy. The environmental assessment process, for example, includes legislated timelines. We are, of course, very pleased that it happened at last.”

Along the way, Oberti met Grant Costello, a long-time ski racing coach and fellow passionate skier, as well as a real estate expert living in Invermere. Costello became senior vice-president of the company, Glacier Resorts Ltd., and was part of the skiing group in March. Oberti stresses that Jumbo will not be real estate-focused. For him, it’s about the skiing. “Many other mountain resort projects in North America are driven by and dependent on real estate,” he says. “This project will have some real estate, but real estate is not what motivated or will carry it. Jumbo was conceived and will be built for real users—in summer as well as winter.”

“…OUR VIEW WAS THAT THE PROCESS SHOULD FOCUS ON THE DESIGN AND WHETHER IT WAS ACCEPTABLE FROM AN ENVIRONMENTAL, AESTHETIC AND ENGINEERING STANDPOINT.”

The descent from Glacier Dome was pleasantly powdery. Although flanked by gnarly terrain, visually stunning and copiously snowed-upon, the main lift-serviced area is pure intermediate heaven. The slopes are more than merely broad and the pitches are vast, with virtually no limit to the width of runs that could be roomed. Just what mainstream skiers crave.

Oberti had found the area back in the mid- ’80s, “purely from mapping”, after being commissioned to hunt for “the ideal location for an ideal ski area for North America”, one that would optimize all the ingredients of terrain, snowfall, snow quality, climate, location and year-round use. Within a few years Oberti had found the Jumbo Creek area. He skied Glacier Dome for the first time in April 1990 with his son, Tom, heli-skiing operator Roger Madson, long-time Ski Canada contributor Don Bilodeau and two potential investors. Oberti immediately began work on a resort proposal, and presented the formal application to the B.C government the next year.

Opposition materialized. The more studies were completed and regulatory steps satisfied, the more stridently opponents claimed that Jumbo was “pristine” or “wild”. Although the area has been logged, has been mined, has an existing road, held a village for decades, and is the long-time scene of heli-skiing and snowmobiling, opponents insisted that building even half-a-dozen lifts would bring environmental disaster. While the local Shuswap came to see it as an opportunity, the Ktunaxa First Nation to the south remains opposed.

“The opponents come from a lot of angles,” says Oberti. “A lot of people are genuinely concerned but don’t have the right facts, others have friends or relatives who are opposed, some are business owners cowed by the intensity of some opponents and some are very negative people who feel Jumbo must be stopped at all costs.”

One of the opposition arguments runs along the lines that we don’t need “yet another” ski resort. Leaving aside that Canada has a market economy in which businesses are supposed to compete, Jumbo isn’t yet another” anything: it will be the first and only true high-alpine ski resort in North America. Plus the only ski area in Canada besides Sunshine Village that sits atop the main spine of a major mountain range, not merely out at the edge of things or on an obscure hilltop in the woods. It will have among the highest annual snowfall on the continent and, at buildout, the number- one vertical.

Several dozen protesters showed up at the heli-pad at Panorama on the morning of our skiing—including some young women who have race-trained on Farnham in summer. That evening, down in the Best Western Hotel in Invermere where I was staying, the young woman at the front desk commented, “I find it ironic that these girls think it’s fine for them to ride diesel-powered snowcats so they can ski on Farnham in summer, but the rest of us should not be allowed to ride a lift and have the same experience.”

The run’s final pitch was the most satisfying: nicely inclined apron beneath towering cliffs, dappled with larches, ending at the forest. Jumbo Glacier Resort, too, still has a substantial pitch to navigate. The B.C. government must make good on it’s intention to create a mountain resort municipality, similar to Whistler’s or Sun Peaks’s governance structure, which s needed to secure local permitting. And Oberti must line up the Phase I construction financing of $225-$550 million. He has been working with a major French lift company plus the pension fund that finances it, and several French officials were in the March skiing party. Lastly, Oberti will almost certainly have to run a gauntlet of protesters (or worse) when the earth-moving equipment and flatbed trucks laden with lift towers finally rrive. Oberti hopes to launch limited public summer skiing on Farnham next year, and begin construction of the gondola in 2014.