As the expectations of skiers and technology changed, preparation of our slopes evolved as well.

The first time I thought a groomed run might be more than learning terrain was when I demoed a pair of Elan SCX, one of the first shaped skis. I took them for a rip on the lower slopes of Lake Louise, a part of the resort I normally only graced because there was no other way to get home. Like popping a pill, the SCX’s deep sidecut turned predictable groomers into a rolling playground for air turns, hand-dragging carves and a new ski phenomenon: trench digging.

Since that magic run in 1993, I’ve become more and more of a fan of corduroy as skis have become more shaped, powerful and easier to carve. This fits a familiar pattern for snow grooming and snowcats. Their histories followed ski innovation, and is a more exciting tale than most would think. It started with horses, met tragedy in Antarctica, tempted life and limb at Winter Park Resort, made Olympic halfpipe possible and is now set to combat climate change.

The grooming side began on the road. Long before recreational skiing took off, teams of horses compacted snowy roads for sleighs and then tires, using agricultural rollers. By 1939 ski areas had adopted the concept, with a tractor, not horses, compacting early-season snowfalls so they wouldn’t melt or blow away.

As ski technology improved, the sport got easier and the slopes got busier. Wood skis and leather boots, moguls and ice: it wasn’t a good combo for new skiers learning the young sport, let alone the hot-doggers. According to the 1945 American Ski Annual, New Hampshire’s Cranmore Mountain Resort was one of the first hills to fluff up the slopes, while those of us who have or had skiing parents were at après-ski.

“We remedy this condition by scarifying late in the day, creating a powder surface which freezes during the night to the harder snow below,” reported Phil Robertson, the resort manager. He described the process as a tractor pulling a “magic carpet,” a network of chains with spikes that weighed 1,200 pounds.

Moguls were a tougher obstacle. It wasn’t until 1950 that Steve Bradley developed the Bradley Packer-Grader at Utah’s Winter Park Resort. The contraption had a spring-loaded steel blade to shave off the top of the moguls and, in its wake, a “slat roller” to turn over and then flatten the snow. A ski patroller on skis steered the 700-pound contraption down the slope.

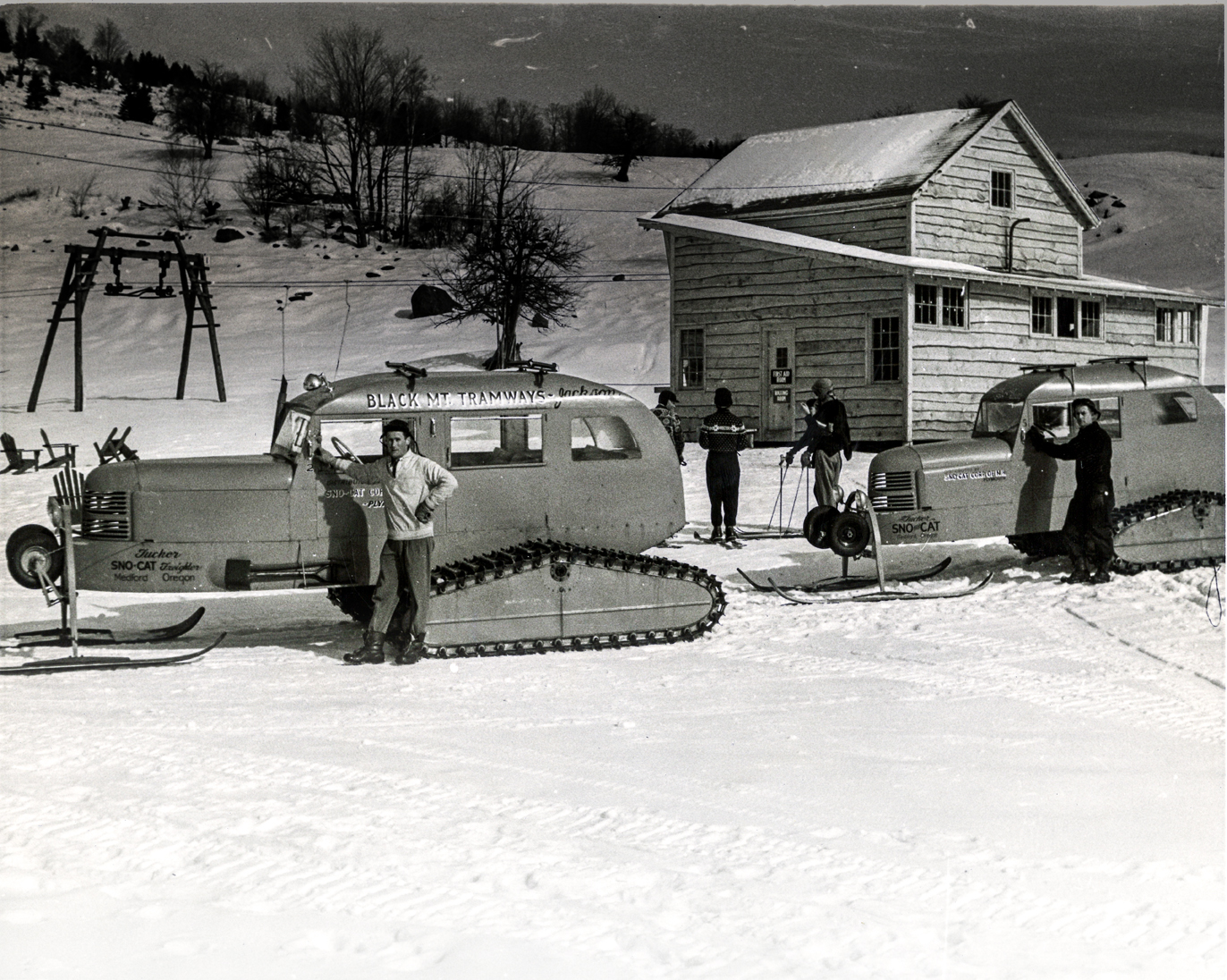

Meanwhile, the vehicle side was evolving, too. Captain Robert Scott’s disastrous attempt to reach the South Pole in 1911 and 1912 used some of the first tracked vehicles. They failed, Scott turned to ponies and he and his entire expedition died in Antarctica. It wasn’t until after the Second World War that the track technology, honed with tanks, had developed enough to enable a reliable on-snow vehicle. Tucker Sno-Cat Corporation launched one of the first in the post-war years and its trademarked name became the Kleenex for the genre. Over the decades several other brands got into making snowcats, including the DeLorean Motor Company, Logan Machine Company (LMC), PistenBully and Bombardier Recreation Products.

By the 1960s the two branches of the family tree met and snowcats were dragging around heavy mats, Packer-Graders, rollers and all kinds of homemade snow-grooming concepts.

To smooth out the runs of the Pinnacle Ski Club in Maine, Jeff Lancaster remembers “sitting on a snowmobile with my dad, dragging a chain-link fence weighed down with cinder blocks.” The most popular DIY was probably a snowcat pulling a culvert, says Lancaster, now the Western Canada sales rep for PistenBully, a leading snowcat manufacturer. Because culverts spiral, resorts capped the ends so they would roll straight. These were a common sight, rotting in the weeds at resort boneyards, by the 1980s.

The reason for their demise was the power tiller. Developed individually by PistenBully, Bombardier and LMC around the same time, the rotating bar with teeth churned through snow and ice to produce soft granules. It required power from the snowcat, a shovel upfront to flatten the snow and a pressurized grooming surface behind. This integrated machine looked a lot like the groomers of today and produced a similar corduroy.

The modern snowcat can navigate most blue terrain, but, even today, it doesn’t have the power to push and compact snow on pitches greater than 30 degrees. That’s where the winch cat stalks in. With a steel cable attached at the top of the pitch, the cat pulls itself up and lowers itself down as it grooms the run.

“Astronomically expensive,” Lancaster says, “they were a luxury for a while.” But as shaped skis made corduroy more fun, the demand to groom the steeps increased, and so did the importance of winch cats. Now most resorts have at least one as part of their grooming fleet.

Simultaneously, snowboards were taking over the slopes and then twintip skis made their appearance. The halfpipe was born and groomer manufacturers invented equipment to keep the features uniform and safe. A variety of Pipe Dragons and other specialized equipment emerged that carefully, and painfully slowly, carved the sides into perfect curves. As resorts realized the crippling cost of building and maintaining halfpipes in the early 2000s, most abandoned them for terrain parks and traded the pipe equipment for nimble cats designed specifically for building tabletops.

That brings us up to the present. The next step is to go electric. PistenBully already has hybrid cats, similar to plug-in electric vehicles, that use a diesel generator to recharge an electric motor. Last year it began testing the first all-electric snowcat, which it hopes to have available for purchase in a winter or two. Lancaster says resorts are clamoring for the e-cat, particularly the burgeoning indoor ski hill market, but a bigger focus is on services.

“The future is all about efficiency,” Lancaster says. “In the past you didn’t know what was happening with your grooming fleet at night. Now you can track everything.”

GPS and other metrics allow a manager, say in Vail, Colorado, to analyze fuel burned and acres groomed in Whistler last night. Now PistenBully is adding the Z-axis: technology to see into the snow.

In the past, the best a hill could do if it wanted to know how much snow was on a run was send out staff to drill test holes. The new technology uses satellites and GPS to compare measurements taken before the snow falls with the present position of the snowcat. The difference is the depth of the snow and it’s displayed, in real time, on a screen in the cat. With the knowledge, a resort could see snow depth across the entire hill and a driver knows exactly where to take and add snow.

This info can change a resort’s fortunes.

After a dry November and December two years ago, the technology enabled Sun Peaks Resort to spread its man-made snow as evenly as possible for the important Christmas season. “They were able to have 80 per cent of their terrain open, despite not having very much natural snow,” says Lancaster. This ability will become increasingly important, he figures, as winters come later and melts happen earlier with climate change.

It’s the latest evolutionary pressure on the sport and one grooming will be key in grappling with. So while no one can predict what the next skiing revolution will be, after more than a century of development, it’s a pretty safe bet that snow grooming will evolve right along with it.