Since Tod Mountain became Sun Peaks more than 20 years ago, the resort has maintained a well-mapped road into the future.

By Andrew Findlay // PHOTOS BY ADAM STEIN from Fall 2013 issue

You can’t pretend to be something you’re not and expect to fool many people for long. Pull into Sun Peaks Village and the view that unfolds before your eyes screams out “family friendly.”

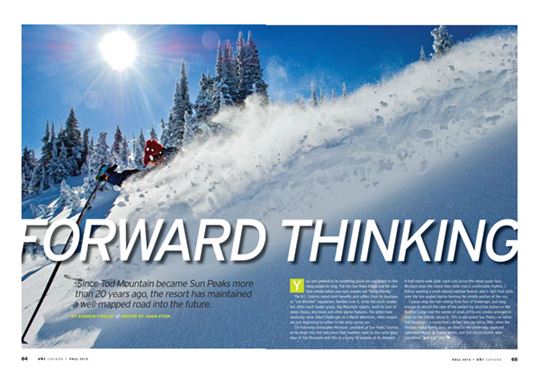

The B.C. Interior resort both benefits and suffers from its boutique or “not Whistler” reputation; families love it, while the much smaller but often much louder group, big-mountain rippers, mock its lack of steep chutes, big bowls and other alpine features. The latter have obviously never skied Challenger on a March afternoon, when moguls are just beginning to soften in the early spring sun.

I’m following Christopher Nicolson, president of Sun Peaks Tourism, as he drops into this test piece that hearkens back to the rustic glory days of Tod Mountain and tilts to a gamy 50 degrees at its steepest. A half-metre-wide glide crack cuts across the steep upper face. Nicolson pops the chasm then sinks into a comfortable rhythm. I follow, working a small natural halfpipe feature skier’s right that spills onto the low angled reprise forming the middle portion of the run.

I pause atop the hair-raising final face of Challenger, just long enough to absorb the view of the peeled log structure known as the Burfield Lodge and the warren of small 1970s-era condos arranged in rows on the hillside above it. This is old-school Sun Peaks—or rather Tod Mountain—a scene that’s etched into my skiing DNA, when the Findlays had a family pass, we skied in the universally approved outerwear known as frozen denim, and 210-cm GS boards were considered “hot-dog” skis.

************************************************************************************************************

Last March I checked into a condo at Crystal Forest with my wife, two young kids and mother. I was here to visit new-school Sun Peaks, to get a behind-the-scenes look at the evolution of this mountain from rugged, happily dysfunctional Tod to the well-oiled creation known as Sun Peaks Resort—an evolution that began in 1992 when Nippon Cable stepped in as the new owner and I had departed my hometown of Kamloops to pursue other distractions.

The morning after my two-hour nostalgic rip with Nicolson, I’m riding the Morrisey Express with Mountain Operations Manager Jamie Tattersfield, who was imported from Whistler in the early days of Nippon Cable’s tenure. Tattersfield has been here through every step of Sun Peaks’s expansion, and I’m quick to learn that there’s nothing haphazard about run design and development. The Morrisey glides above Rider and Still Smokin’, two runs that were experimental in nature when Tattersfield and his team designed them in 2003. They called it “groomed glading.” In essence, it’s a wide buff-groomed blue run punctuated with patches of trees, the aim being to give character and relief to what would otherwise be a forgettable ramble down a swath cut through dense forest.

“Ski Canada once ran a snarky bit about Sun Peaks investing in “groomed glading,” recalls Tattersfield, referring to a Best of Skiing in Canada “awards” that poked fun at the seeming oxymoron. He then adds, with the barely containable satisfied smile of vindication, “But two years later there was a retraction.”

After off-loading, we slide to a stop next to a billboard that shows what’s groomed and what’s not. Tattersfield busts out a folded map of Sun Peaks—past, present and future. When I last spent any amount of time here, Tod Mountain was it. Today Sun Peaks is a trifecta of mountains: Tod, Sundance and Morrisey.

Tod proper is a bald dome with a beyond-the-ropes summit that sits at 2,152m and is the repository of my early skiing memories with runs like Chute, Crystal Bowl, Headwall and Chief. I once went head-to-head with Craig Ellis in a psychedelic-drug-infused distance ski jumping competition at the base of Chief. Ellis attempted a 360 with his 223cm Fischer holy tips and blew out of both bindings mid-flight. I landed on my rump, consequently ripping out my heelpieces and annihilating my VR 27s. (The judges examined the resulting craters and awarded Ellis gold.) Old-school Tod Mountain is home to what long-time Sun Peaks resident, speed skier and publisher of the local rag, SPIN News Magazine, Adam Earle calls the compulsories: Chief-Roller Coaster, Chief-Expo and Chief-Challenger.

After 1992, the first phase of expansion opened up the Sundance zone, where a matrix of blue and green runs rises above the village extensive enough to keep a thousand SUVs full of American families happily amused. And then came Morrisey, on whose rounded, densely wooded summit we’re standing, with its north-facing runs that plummet in increasingly steep lines as you travel skier’s left across the mountain. Today Sun Peaks, at 1,488 hectares, proudly maintains the second most skiable hectares in B.C., after Whistler Blackcomb.

“We’re getting ahead of ourselves with terrain. Our run capacity is out-pacing our lift capacity by a considerable margin,” says Tattersfield, before sharing some ski area nerd data to back up his claim. Sun Peaks’s lift capacity, measured in vertical transport metres per hour (VTM), sits at 7,720. Skier Carrying Capacity (SCC)—a number derived from terrain difficulty, skier vertical demand and VTM—is almost double at 14,060. It sounds impressive, but the dearth of humans impresses me more than the stats, as we snake our way down the gladed grooming of C.C. Rider, with crowds as thin as the bleachers at a REO Speedwagon tribute band concert.

Despite the abundance of terrain, expansion continues within the resort’s prodigious 4,139-hectare designated Controlled Recreation Area. It’s 11:00 a.m. and the carpet still takes an edge as smoothly as it would if the groomers had buffed the run for our personal pleasure moments before we arrived. I follow Tattersfield, arcing super-Gs around the namesake gladed grooms. We reload Morrisey then rip down Delta’s Return, shedding our skis at the bottom before shuffling across the covered pedestrian overpass linking the Morrisey pod with the main village. Then we put our skis back on and skate over to load the Sunburst Express, which years ago replaced the aged, 18-minute journey into the clouds on the double Shuswap Chair.

Sun Peaks’s master development plan gets reviewed every three years, and Tattersfield says people are always “really interested in what we’re going to do next.” The future is where we’re headed now, the ultimate phase of the resort’s development that will help boost the array of intermediate and advanced offerings. First up is another 70 hectares of run-cutting on West Morrisey, steep and shady, then there will be more intermediate terrain opened by the still to be built Orient Express east of Sundance, followed by the eventual expansion into the hallowed territory of Gil’s Hill, which will include a chair and surface lift.

For me, this glimpse of the future is a journey into the past. By the time we offload the Crystal Chair, an ancient triple that shuttles skiers to the top of Crystal Bowl, I’m lost in a fog of memories, which has me ducking beneath ski area boundary ropes and sidestepping, bootpacking and traversing with fellow ski bums to get first tracks on the steep natural glades of Gil’s Hill. This has been a favourite slackcountry haunt for decades, and no doubt when the resort eventually absorbs this pod into its in-bounds offerings, there will be detractors. The same way some diehard locals scoffed nearly 20 years ago when management transplanted a T-bar from lower Expo to West Bowl, in the windswept alpine below Tod Mountain’s true summit. The detractors usually come around. Opening Gil’s Hill will be a game-changer for the mountain from an operational standpoint.

“We don’t have a snow safety program yet, so when Gil’s Hill is opened, we’ll be bringing on avalanche forecasters,” says Tattersfield, before dropping into one of the short, steep but sweet lines on Gil’s Hill that I coveted time and time again as a kid, who was quite honestly somewhat oblivious to avalanche hazard.

Today the snowpack is stable but the quality unforgiving; the breakable melt-freeze crust doesn’t square neatly with my halcyon Gil’s Hill memories. We hack our way down then pick up a knee-jarring traverse trail through dense forest that deposits us on 5 Mile, a wide, sweeping green run chalk-full of green skiers and the occasional racer who uses the populace as moving pylons and gates.

We take the connector that leads us to Sundowner, beneath the Sundance Express. Tattersfield stops for a teachable moment. When he made the move from Whistler decades ago, he says he never expected to become a forester by default. Lodgepole pine trees around Tod have been savaged by mountain pine beetle, and spruce to a lesser degree by bark beetle. As best as possible, the natural cycles of forest ecology have been incorporated into run design and layout. The resort decided to start harvesting beetle-killed trees in the late 1990s, while the timber still had market value. In turn, revenue from the harvesting subsidizes new run development. For the past two decades, the resort has employed the same father-and-son logging duo, who specialize in light footprint harvesting.

“We’ve always tried to emulate natural processes with small patches and selective harvesting,” Tattersfield says, bending down to adjust his boot buckles. “On the one hand, we’re stewards of the environment; on the other, we’re logging trees.”

Sun Peaks takes its commitment to the environment seriously. In 2004, it became the first ski resort in North America to receive ISO 14001 certification for environmental stewardship. This rigorous, internationally standardized environmental management system governs water use (for example, installing only ultra-low-flush toilets), using recycled paper and other recycled products whenever possible, incorporating energy-efficient building design and a host of other sustainability objectives. Sun Peaks remains one of just three resorts in North America with this honour, along with Jackson Hole and Snowmass.

That night I meet up with Adam Earle, who joins me for the regular Wednesday-night fondue feast at the Sunburst Lodge, followed by a torchlight ski down 5 Mile. Earle represents the kind of local spirit that has kept the resort grounded throughout its 20 years of modern development since Nippon Cable’s tenure began in the early 1990s.

Earle was working at the Longhorn Pub in Whistler in 1989 when he lost his job. He loaded up a Toyota Corolla, puttered over the Duffy Lake Road and landed at Sun Peaks, where he quickly immersed himself in the local speed-skiing community championed by the likes of Kenny Dale, Don Gagne and other long-time locals.

“I never left. I met my wife and we started a media company,” Earle says. He has witnessed—and documented through his local media activities—its growth from a 50,000-skier-per-year, gloriously precarious mom-and-pop operation, to today’s polished four-season resort that welcomes a half-million visitors annually. Scrape away the polished veneer and it’s still basically a ski hill full of people having fun.

We’re sharing a table with a bevy of 10, mid-40 women from Winnipeg on the sort of winter ski road trip during which the things that happen on the road stay on the road. They end up turning the entire fondue night into a massive singalong, commandeering the evening’s guitar-playing duo into their personal live jukebox. Inevitably, Don McLean’s “American Pie” gets trotted out.

Later, bellies full of raclette and chocolate, we stomp out into the evening for a twilight run down 5 Mile, a family-friendly favourite that hearkens back to the earliest days of Tod Mountain, to a brisk November day when “Flying” Phil Gaglardi, the Kamloops region’s provincial political representative at the time, offloaded the Burfield Chair wearing a long wool overcoat to celebrate Tod Mountain’s opening in 1961.

The ladies from Winnipeg giggle their way down the mountain. I look up at the steep glades of Gil’s Hill disappearing into the darkness—the future of the resort’s expansion into more black-diamond terrain—then follow Earle as he butters the edges of 5 Mile with speed. I take a brief detour onto a little knee-grinding pump track of a forest trail that parallels the run, just for the fun of it, and for a moment I’m that scrawny kid in frozen jeans and a red down parka.