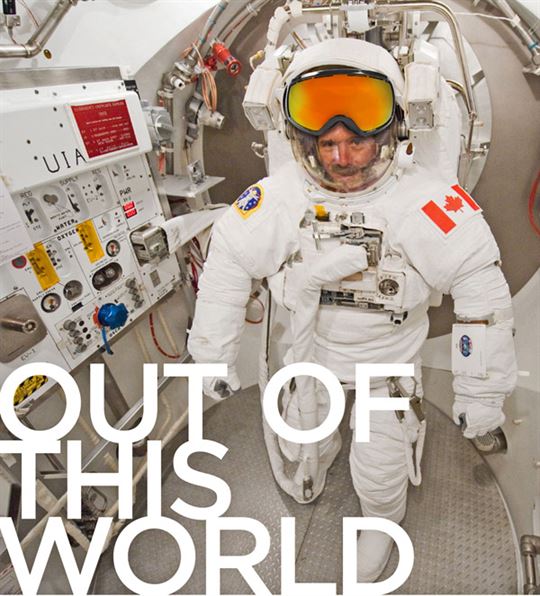

When Chris Hadfield finished his tour of duty as commander of the International Space Station, he couldn’t wait to swap his space suit for a ski suit.

BY FRANK BALDWIN

Colonel Chris Hadfield started skiing at the age of four when his father taught him on the gentle, snow-covered hills of a nearby golf course in southern Ontario, where he was raised.

While still at high school he landed his first job working as a ski instructor at the Glen Eden ski area north of Burlington, Ontario. “I did a lot of racing at provincial level, but it was working as an instructor that really improved my skiing,” said Hadfield. “Teaching the fundamentals seven days a week massively improves your technique, and by the end of that first winter I couldn’t wait to head to Lake Louise or Sunshine in Banff since I knew I could ski just about anything.”

He carried on skiing after joining the Canadian Armed Forces and graduating with a degree in Mechanical Engineering from the Royal Military College in Kingston, Ontario. He later had to put the sport on hold when he started training to be an astronaut—which eventually led to him becoming the first Canadian to command the International Space Station and go on spacewalks.

“Astronauts aren’t allowed to ski pre-launch because there are fears that we might injure ourselves or break something that takes a long time to heal,” said Hadfield, “so I didn’t ski for 21 years while I was an astronaut.”

When his feet were finally firmly back on earth, Hadfield had to wait to ski because of bone density loss from spending time in space.

“We don’t fully understand why we lose bone density in space,” explained Hadfield, “but you sure can see the effects. The first time you go to the bathroom in the Space Station your urine is already full of calcium and minerals. You lose about one-and-a-half per cent of your bone density a month, so after five months I had lost eight per cent. Unfortunately, I lost it in an area that is really important for skiing—across my hips and upper femur.”

It took several months for Hadfield’s bone density to return to normal and last winter he was able to make plans to head back to the slopes.

“After I finished high school, I hitchhiked around Europe for about nine months and was able to ski in St. Anton, Zermatt, Andermatt and also in the Tatras Mountains between Slovakia and Poland,” he said.

Does Hadfield play favourites?

“There are many great ski areas in Canada, but if I had to choose one it would be Whistler Blackcomb, which I think are the best mountains in the world. For my perfect day I want somewhere where there is plenty of powder but also a lot of variety. There must be great views, but it shouldn’t be too high because you then have to deal with the altitude—which you may find amusing for someone who spent five months working in space, thousands of feet above earth.

“So for me the best skiing in the world is in Western Canada since it combines all those things. I have skied in Banff many times—Lake Louise, Sunshine and a little bit of Norquay, and I like all of them, but Whistler Blackcomb, with all of the back bowls, vistas and huge variety of snow conditions is still top of my list.”

After spending extended time on the cramped International Space Station, you would think Hadfield could be tempted by the lure of a spacious, luxury hotel. But he has other ideas.

“The best place to stay is somewhere where you don’t have to get on a lift at the start of the day,” explained Hadfield. “Whistler has a few places on the mountain like this, such as the Simon Fraser University cabin. You can wake up early, grab breakfast, step outside straight onto the snow and put on your skis. That to me is perfection. I would then ski down to the lifts before the lines started to form, get up the mountain and head for the lifts where you know there are not going to be too many people so you can get in as many runs as possible.

“I would definitely ski with family and friends on my perfect day since it’s a delight to be able to share the experience with people. We don’t even need to do the same runs together, just as long as we keep meeting up to compare notes. Skiing itself is extremely personal and individual, but I like the fact that it’s broken up by getting on a lift and sitting next to people, talking to them and listening to their experiences.

“I like the feeling of coming off the lift at the top and getting yourself ready. And as you ski off, you then have a choice. Do you fancy an easy swoop down an intermediate run, or is it going to be moguls or maybe a little off-piste? My perfect day would be to ski all day right up until the last run when dusk is starting to fall.”

What would Hadfield do for après ski on his perfect day?

“Ski days are pretty stimulating and physically exhausting. So I am happy to relax. If I want loud music I’ll go to a city. Skiing is too precious to confuse it with disco. Maybe if there’s a hot tub, sauna or even a hot springs nearby, I’ll go for a soak, but probably the most boisterous après ski I take part in is having a steaming hot sauna and then running outside for a naked snowball fight or rolling in the snow before rushing back into the sauna.”

And what about food? Surely after surviving on space meals Hadfield might like some cordon bleu cooking?

“I don’t need anything too fancy for dinner,” he said. “I prefer to take in some carbs such as pasta while chatting with friends, and then play some guitar. A relaxing dinner and a bit of music is the perfect evening for me because this is still externally stimulating and is like an extension of the day on the slopes.

“When I was in space, I wanted to photograph ski resorts but it was just too time consuming to be able to identify individual ones and get pictures. But I did take pictures of the Rockies in the U.S. and Canada, the Alps, the Himalayas, the Andes—they are too dramatic not to.”

Did he look down at them and wish he were skiing?

“I love skiing, and being in snow-covered mountains on a clear, calm, sunny day is one of the nicest places on earth to be—but being weightless up in space is even more fun!”

ROLL OF HONOUR

Chris Hadfield is a pioneer of many historic firsts and to Canadians he is a more famous astronaut than Neil Armstrong.

In 1992 he was selected by the Canadian Space Agency as a NASA Mission Specialist—Canada’s first fully qualified Space Shuttle crewmember. Three years later, aboard Shuttle Atlantis, he was the first Canadian to operate the Canadarm in space, and the first Canadian to board a Russian spacecraft as he helped build space station Mir. In 2001, aboard Shuttle Endeavour, Hadfield performed two spacewalks, and in 2013 he was made commander of the International Space Station, the first and only Canadian to ever command a spaceship.

During his multi-faceted career, Hadfield has intercepted Soviet bombers in Canadian airspace, lived on the ocean floor, been NASA’s director of operations in Russia, recorded science and music videos, and is a best-selling author.

A heavily decorated astronaut, engineer and pilot, Hadfield’s many awards include receiving the Order of Ontario, the Order of Canada, the Meritorious Service Cross and the NASA Exceptional Service Medal.

He was named the Top Test Pilot in both the U.S. Air Force and the U.S. Navy, and has been inducted into Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame. He has been commemorated on Canadian postage stamps, Royal Canadian Mint silver and gold coins, and on a Canadian five-dollar bill along with fellow astronauts Steve MacLean and Dave Williams.