The flavour of Vermont is a big draw for eastern skiers looking for something sweet.

BY IAN MERRINGER in Fall 2015 issue

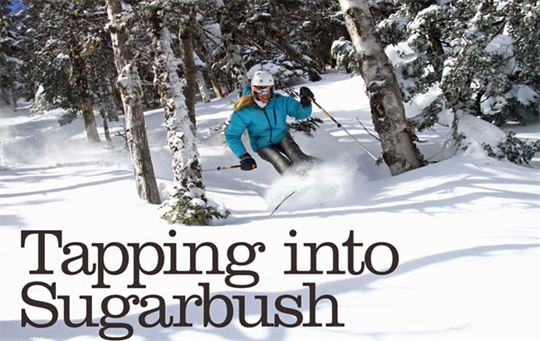

Walking into Lincoln Peak Village from the parking lot, you get a clear view of the western wall of Lincoln’s bowl, home to Castlerock Peak and the rocky Headwall. The Headwall is the sort of marginal terrain that catches the eye and dares you to wonder if it’s skiable. Castlerock is of the traditional steep and bumpy variety.

A few steps ahead of me, two young guys with skis slung over their shoulders and pant cuffs dragging in the salty gravel take note.

“Right there, Fudge. Look straight up,” says the one on the right, who I’ll call Chunk.

“I’m down for that,” replies, presumably, Fudge.

In 1959, the Castlerock chairlift established Sugarbush as the proving ground for eastern skiers seeking expert terrain. The area doesn’t present as an overly significant piece of real estate on the trail map—it’s really just four runs—but it looms large in Sugarbush lore. It was a bit of grit defenders could point to when the resort started getting smeared as “Mascara Mountain,” a place frequented by overly made-up socialites from across the Eastern Seaboard in the 1960s.

Chunk and Fudge could have Castlerock to themselves for a little while today, as far as I’m concerned. After getting my kids set up at ski school, I opt to stay on the Super Bravo Express Quad—and not just because of its enthusiastic name. I had read the snow report that morning. As much as I’m happy for the skiers who had enjoyed the previous two days of glorious, sunny spring skiing, the cold front that followed us down I-89 from Canada the night before left me wary.

The previously thawed mountain had totally set up overnight and is a few days away from a fresh covering of snow, a topic of conversation at Allyn’s Lodge, halfway up Lincoln Peak. The front door to Allyn’s remains roped shut from the inside. Apparently it was blowing open when anyone opened the back door. On our visit, about a dozen people are inside the small lodge, lounging on the couch in front of the fire or, it must be said, at tables, alone, playing on their phones.

“What a difference a day makes,” says Todd Spencer from Pennsylvania, remarking that overnight the temperature had dropped and the wind had increased dramatically. Moving the conversation away from what I had recently missed, I learn he still makes the six-hour drive twice a year from his home to Sugarbush instead of other Vermont resorts because, in his words, “There are more Quebecers and Bostonians here, fewer New Yorkers.”

It’s a sentiment expressed, albeit more delicately, by Sugarbush’s head pitch person (also president and part-owner) Win Smith, who joins me for a handful of runs. When, after the first run, he changes his skis to better suit the conditions, it’s clear that this is one ski resort owner who spends a lot of time on skis, keeping in direct touch with his domain.

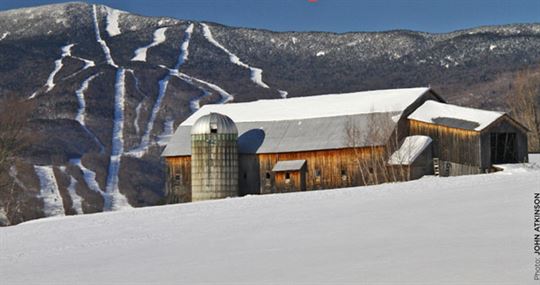

“Sugarbush looks and feels like Vermont,” says Smith proudly. Having driven in the night before, I don’t need much convincing. The entire Mad River Valley is Vermont-quaint. There are no chain stores or restaurants, no fast-food lights nor billboard advertising. It’s true this is achieved by local ordinances, but they work.

He uses that magic word “local” liberally. It can be a stretch to call on that appeal at a ski resort, where the clientele can be transient almost by definition, but Smith backs it up by citing numbers: 55 per cent of Sugarbush skiers are season pass holders and a third of all visits are from within an hour’s drive (Burlington, where Porter Airlines flies regularly in the winter, is 75 km).

Since buying the resort in 2001, Smith and his group have proceeded slowly. “We aren’t real estate speculators,” he says, suggesting that a lot of other resorts had overbuilt accommodation at the expense of the on-hill facilities.

There’s a notable exception to the professed pivot away from real estate. The upscale Clay Brook Hotel and Residences, built to resemble a trim red Vermont barn, opened in 2006 and houses 61 units as well as Timbers restaurant. By the numbers, our suite has two bedrooms, three televisions, one four-poster bed and at the kids’ count, 25 light switches. There are no dark corners beyond the reach of illumination at Clay Brook.

It also has an abundance of staff, and attendant tip jars. When we pulled up to the curb on arrival, my eye-rolling wife ridiculed me when I tried to find a place not subject to valet service. We had just completed an eight-hour drive from Toronto. I had succeeded in not stopping to buy any food (bathroom breaks permitted) and she was going to enjoy watching all my packed-snack savings get sucked into a vortex of tips for valet parking, luggage porters, overnight ski checks and, why not, cafeteria cashiers.

But if you’re going to take a ski trip with kids, the ski-in/out convenience of a spacious, restaurant- and hot-tub-equipped luxury lodge is worth throwing around a few dollar bills (folded up, so no one can tell how many are bundled).

As comfortable as Clay Brook was, our second night was to be at a nearby inn, so after springing the car from the valet we head out for dinner on the road that follows the Mad River, a lively waterway obviously further enraged by the recent warm spell.

First to dinner. If someone were to design a casual place that you could go after a day of skiing for a restorative meal while barely noticing your kids, that place would be called the Mad River Barn and it would be a 10-minute drive from Sugarbush.

Stuffed animals with at least part of the bodies protruding from the walls included a moose, caribou, bobcat, bear and an owl. Take advantage of the foosball, air hockey and shuffleboard before you eat. The fare is solid enough that after the meal you’ll be content to sit and sift through the loose Trivial Pursuit cards piled in Bundt pans in the centre of the tables.

The so-called Barn has 18 rooms that fit up to six people each, but we were staying down the road at White Horse Inn, a less rustic, more classically styled inn of 26 rooms. It’s one of at least 15 smaller lodges and inns within a 20-minute drive of Sugarbush and neighbouring Mad River Glen. White Horse co-owner Bob Heffernan says he never bothers to lower the Canadian flag that flies out front, since there are always a few Canadians on the premises.

In the era of cavernous-condos competing with hyper-equipped resort lodging, where concierges lose their breath before listing all the amenities like health centres, games rooms, spas and swimming pools, the charms of a simple Bob Newhartish inn like the White Horse rest on two basic fundamentals, price and good breakfasts. You can still find shelter for a night without all the extras you don’t want to pay for. A hearty breakfast, however, should not be considered an extra and Bob’s partner Allen puts on the kind of spread every morning that might let you skip lunch at the hill.

But which hill? At Sugarbush you get to choose from two distinct mountains: Lincoln Peak and Mt. Ellen, linked by a 12-minute express quad chair that services no runs but offers a wildly scenic, mid-mountain trip between the two areas. (The alternative is a 25-minute drive between the two base areas.)

Lincoln gets the most attention, with its new base area and five main chairlifts fanning out to cover a bowl that offers truly varied terrain.

Mt. Ellen is the slightly taller, skinny and decidedly shy stepsister of the two. It has just under half the terrain, but just over a quarter of the skier traffic, with a significant portion of that being relegated to the huge terrain and rail park. So, with its low skier traffic and a mostly linear trail network, it means there aren’t too many crowded junctions, making the long, fall-line cruisers perfect places to take kids who are still honing their skills on intermediate runs. F.I.S. and Lower F.I.S., though a black-diamond run, falls a full 800 metres of vertical but only passes through three junctions with other runs. Needless to say it’s the sort of place you can really get a rhythm going.

But what set Sugarbush apart for me when deciding where to go was not Lincoln or Ellen, but what lies in between. Slide Brook Basin is huge, wild and effectively in-bounds. It’s 810 hectares of tree-skiing terrain. That’s almost four times the total of the other two mountains’ runs combined.

As someone who remembers having lift tickets pulled for leaving the trails to ski the woods as a kid, I had asked Win about this wholesale liberalization of off-piste policy at Sugarbush the day before.

“The treelines are like the Mexican border,” says Smith. “We couldn’t keep people out if we tried. Tree skiing is the maturation of the sport. We can’t control it or patrol it, but we have full cell phone coverage. The serious injuries are on the sides of intermediate trails, where skiers are going fast and catch an edge. Injuries in the woods aren’t fatal because the skiers aren’t going fast.”

The benefits go beyond offering interesting skiing to forest-philes. “Tree skiing gets more people off the trails, opening up space on the hill, and the lift lines are shorter, because the runs take longer,” explains Smith.

Much longer, in fact, about 40 minutes top to bottom for a typical run in Slide Brook Basin. But of course, there are no typical runs in Slide Brook, which is the point. Skiers are encouraged to arrange a guide through the ski school, but the overarching philosophy is that, being a basin, groups of skiers who take care of themselves properly will eventually get to the funnel point at the bottom where a bus stops every half hour to take them back to a base area.

Local photographer John Atkinson and I duck into Slide Brook from Lincoln Peak, but you could spend a few years exploring it from the Mt. Ellen access points also.

With its tree canopy being near total, Slide Brook Basin had escaped the more punishing rays of the sun that had radiated many of the open runs a few days earlier. The snowstorm that is expected the next day will wipe the slate clean, but the point, for me, about tree skiing is that the conditions don’t have to be perfect for you to enjoy being where you are.

After a dozen turns I truly have no bearings to guide me, just the knowledge that the fall line leads to a bus stop (a free ride, with no tip jar). Between here and there I have nothing to do but explore a mountain on skis, looking ahead for openings, linking turns and not forgetting to stop often and appreciate what a service I am doing to Sugarbush, by freeing up space on the hill and taking a long time between chairlift rides.

I hope Chunk and Fudge have enjoyed Castlerock. It’s nice to know it’s there if I want it too, but even nicer to know that the Sugarbush of the 21st century has much more than moguls or mascara to offer.

*************************************************************************

Direct: Toronto Island to Burlington

From: mid-December to early April

Frequency: Two to five flights per week

Onboard snacks: You bet