The vastness of France’s iconic mountain destination was the perfect fit for another Ski Canada Readers’ Trip.

Our group of nine stands like soldiers listening to our mountain guide, instructor and drill sergeant Eric bark out orders. With arms flailing, he gesticulates toward the massive Argentière Glacier beyond a much-nearer rollover that could be the start of some excellent skiing for us. Or maybe he’s pointing at a 100-metre cliff that’s obscured…I don’t know. After a minute of raspy loud commands to the French-speakers he pauses, stares blankly at the five Anglo-Canadians for a moment, then takes off like a rocket into the enormous alpine scene.

“What did he say?” I ask Holly, our reluctant translator, quickly.

Squinting a little, she announces, “I think he said ‘No, no, no, you’re confusing this with a holiday!’”

A hearty laugh explodes out of Boris, one of our new friends from Brittany, whom we’ve named Boom-Boom for his skiing style. “Hurry!” he bellows as he pushes off with his poles. “We must not loose heem for a turd time!”

Eric, more mountain guide than instructor, comes to us as Club Med skiers gratuit. But while my kids, and apparently all others on last winter’s Ski Canada Readers’ Trip to Chamonix in March, are being doted on by their instructors, we’re barely keeping up to the pace that Eric has set, and in trouble when we fail. It’s our first day.

Later, while discussing our adventures at après ski, Holly concedes, “I kind of like getting spanked for not keeping up; it wouldn’t be fun if there was no challenge.”

Trevor, whose high school French is worse than mine, even though his high school days are a lot more recent, points out, “There’s a difference between ‘challenge’ and ‘You must anticipate which direction I will go at a fork!’”

It’s only after I returned to Canada that I realized all photos of our smiling group show only Eric’s back—skiing away.

—––––––––––––––––

This was the second Ski Canada Readers’ Trip to a Club Med village, and given there are 19 other winter Club Meds to discover in the French, Swiss and Italian Alps, not our last. Within the magazine’s group of 50, our ages ranged from seven to 70, represented by ’tweens and teens, their parents, party girls in their 30s, single mums in their 40s, couples, men without spouses…skiers from eastern Canada and the west. But other than our first night get-together to collect our woolly Glerups (everyone on a Ski Canada trip receives free après-ski footwear) and a custom team merino toque from Jytte, it was impossible to remain a cohesive group. This is in part due to the size of the property, but also its many all-inclusive distractions.

Club Med Chamonix is in the historic (1904) Savoy Palace and two neighbouring hotels, all of which are connected. A five-minute walk to the town centre, the former Savoy now feels like an austere CP Hotel. The first of three “Palace” hotels that were built in town after the arrival of the railway in 1901, it’s the only one not converted into apartments. With the frontside views of Mont Blanc and backside access to the Brévent-Flégère ski station, it got first dibs on location. The bedrooms may need updating, but the overwhelming views of western Europe’s highest peak, Mont Blanc (4,809m), its colossal glaciers and surrounding jagged teeth make up for the odd taste in bedroom decor. Club Fed’s reputation in the dining rooms and on-mountain restaurants didn’t disappoint; with such choice, I recommend small portions, multiple plates and ski pants with a Velcro waistband.

First ascended in 1786, the storied Mont Blanc, one of the world’s most famous peaks, sees roughly 20,000 climbers summit today—and about 100 who die making the attempt. An 11.6-km tunnel that connects France with Courmayeur, Italy, runs beneath it. Twice, Air India flights have crashed into the mountain, killing everyone onboard. The property line has been fought over since the French Revolution, but its history as the epicentre of mountaineering began when Chamonix was “discovered” by two British aristocrats, Windham and Pococke, in 1741. After writing about their adventures (these two coined the great marketing line “Mer de Glace,” still used today for the glacier ski out of the epic Vallée Blanche run), a trickle followed by a flood of interested travellers began making the trek from Britain and beyond. Chamonix hosted the first-ever Winter Olympics in 1924. And it remains one of the world’s most international ski resorts, where English is almost as widely spoken as in nearby Verbier, Switzerland.

Given Chamonix’s reputation, its relatively small number of 55 lifts is surprising when compared to other mega-French ski domains like Trois Vallées (185 on one pass) or Portes du Soleil (more than 200). It’s probably why all the ski stations that collectively make up “Chamonix” teamed up with Verbier and Courmayeur years ago to offer the more expensive but much farther-reaching Mont Blanc Unlimited lift pass. Curiously, Club Med skiers seem to have the best deal when it comes to lifts, though; its unique pass is good on all lifts including the upper Grand Montets cable car and Aiguille du Midi cable cars and train, all of which are excluded in the more widely sold Chamonix pass.

Chamonix as a destination is made up of several distinct ski areas. The largest and oldest, Brévent-Flégère, begins at Club Med’s back door where a short Poma lift hoofs you up to the main cable car. The sunny side of the valley, Brévent is known for its 1,500m vertical black run to the valley floor (in snowier years than 2015), more intermediate/advanced skiing in the alpine and freeride terrain off-piste.

At the opposite ends of the valley are ski stations with gentler reps, Le Tour/Vallorcine (11 lifts) and Les Houches (17), neither of which could we reach in our six short days.

Not surprisingly with Eric, our group spent a lot of time on the two crowded Grand Montets cable cars that rise more than 2,000m from the base area of Argentière, a 15-minute Club Med or free local bus ride up the valley toward Vallorcine.

Seemingly everywhere in Chamonix, there are more than 10 times the number of off-piste routes down than there are designated runs. But the value of having a guide is appreciated whatever your ski level, whether it’s not having to interpret piste maps or not having to look for the free lunch (all meals are included on a Club Med holiday, they’re just hard to find without a guide sometimes).

Although Eric’s perfect and effortless style, Mach-speed and lifelong mountaineering background are impossible not to be impressed by, he’s an instructor not a mountain guide while wearing his Club Med jacket, so he’s limited to certain degrees of slope where he can take his group as well as a no-glacier travel rule. But Wednesdays are a half-day program at Club Med, so we hired Eric to do a Vallée Blanche run on his afternoon off.

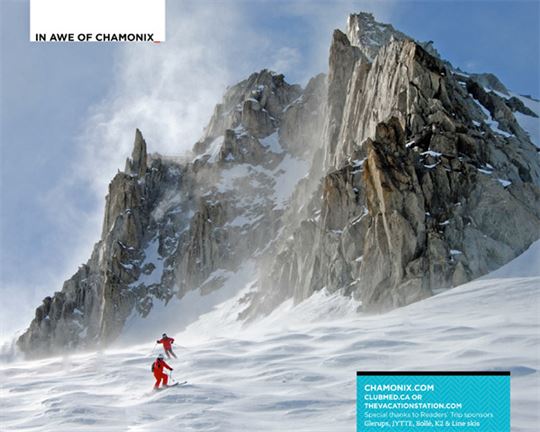

Chamonix’s freeride reputation among skiers is legendary, but like so much skiing in the Alps, your first foray beyond the groomers doesn’t have to be a cornice-hucking,

50-degree, elevator-shaft couloir. A perfect example of this is the fabled 20-km Vallée Blanche itinerary off Chamonix’s infamous Aiguille du Midi that looms above the town.

Just the ride to the top lift station is tremendous and included in Club Med’s Chamonix unique lift pass. A long-held record for vertical rise, 2,800m, the two 60-year-old cable cars next to Mont Blanc remain an engineering feat today. It’s also the start of the Vallée Blanche that will take you several hours to get down.

Although it’s possible to do without a guide, on a sunny day, when it hasn’t snowed and most crevasses are visible, it can be perilous. Even on the tougher sections, the skiing is quite doable for strong intermediates, however, small and enormous (and shifting) cracks in the glaciers remain traps waiting for an unsuspecting skier to drop 25 metres or more into an icy chasm.

Like all others with guides, we carried proper avalanche gear and skied in crevasse-rescue harnesses that Eric provided. Eric carried rescue rope, his cigarettes and, most important, experience.

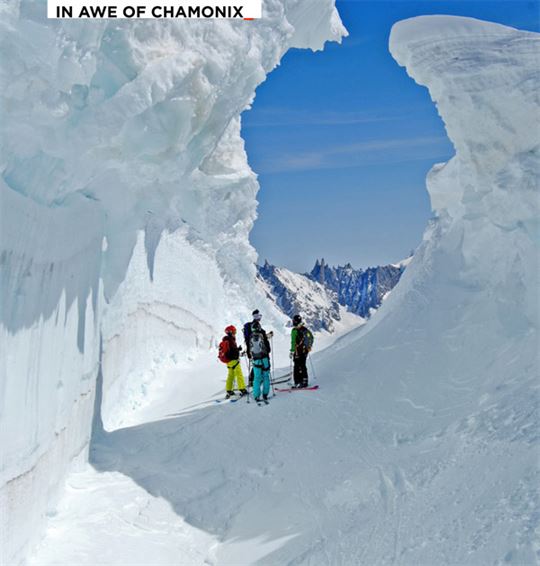

After exiting the second cable car and tunnelling to a bridge between spires, we stopped to take in—and tried to take photos of—our staggering surroundings. Despite having been before, the scene in all directions remains overwhelming. If each of your photos isn’t screensaver worthy, you’ve left your lens cap on. And if you suffer from vertigo, wear blinkers.

The toughest part of our three-hour run was, as always, the walk down from the tunnel’s exit gate to where we donned our skis, about 75 vertical metres below. Called the “Arête,” this relatively low-pitch slope with two routes, either along a ridge or cut right into the ice, might be a five-minute walk—if it weren’t done by hundreds, sometimes thousands of skiers a day smoothing the surface between snowfalls. Also making the jaunt more difficult is knowing that if you should fall and slide beneath the one or sometimes two ropes, certain death awaits down a near-vertical, hanging glacier that drops more than 1,000 metres.

The entire slippery, sugary-snow Arête is roped with metal posts drilled into the ice, so every step on our way required thought. Renting Û10 crampons in town for our boot soles would have made all the difference in the world, but the suggestion was never made. Being tied to the person in front of you and behind you is both comforting (should you fall) and unnerving (should someone else fall). Thankfully, I didn’t have time to question how much help our daycare provider Eric’s little 60-kg frame and cigarette dangling from his lip would be at holding our group of bowling pins on ski boots. Boom-Boom Boris was the first in our conga line; hopefully he wouldn’t be the one to try a counterweight test. The British punters only a few steps behind us, with no guide, nor rope, didn’t exactly calm my thoughts either. But after clutching the rope until our hands were permanent claws, we reached a “plateau of sighs” where skis could be donned and we could marvel again at our stunning surroundings.

For the next hour or so, we skied, and skied more, stopping only to talk about the scenery and take photos of it. Other than two funnel spots where groups choke up to continue onto the Mer de Glace, we saw one other small group before the bottom. This is an incredible combination of snow, ice, rock and sky—no comparison to doing laps at a resort.

We had so much fun that afternoon we took the kids two days later, with a gentler guide, François, a colleague of Eric’s from the 194-year-old Compagnie des Guides de Chamonix.

After a lovely picnic lunch on a warm flat rock outcrop in sun too hot for March, an inevitable discussion about global warming started. We were a 15-minute slide away from where a hundred years ago one could meet the cog rail train back to town. Instead, we would have 15 minutes of stairs to climb before reaching a gondola that would take us up to the railway tracks. Even for teenagers the big melt is excruciating. Slathering on more sunscreen, I told two of my three teens in attendance to “take a good look down the Mer de Glace.” The valley walls full of glacial debris that were covered a hundred metres up not that long ago were like a giant bathtub after the plug was pulled. “I want you to remember this picture so in 20 or 30 years, when you’re here with your kids, you can say, ‘When I was your age, there was enough snow to ski down to those abandoned stairs, now you’ve got a long hike ahead of you.’”