Nothing defines the European skiing experience better than staying a night in a high-altitude hut. Variously called cabanes, refuges, rifugi or hütte, these shelters on the snow are unparalleled anywhere else in the world.

Nothing defines the European skiing experience better than staying a night in a high-altitude hut. Variously called cabanes, refuges, rifugi or hütte, these shelters on the snow are unparalleled anywhere else in the world.

They are also a world unto themselves, where special rules apply and where only a certain type of person goes. I estimate that not more than five per cent of recreational skiers have ever seen the inside of a mountain hut.

Many skiers I know are curious, but just won’t go. They’re put off by the idea of having to cross snow bridges, skirt crevasses and ski tour uphill for a thousand metres or more just to get there. Even more, they are appalled by stories of the primitive living conditions: no heat, no electricity and sleeping 20 or 50 to a room on bare mattresses with not an inch between them. Toilets, like those at Cabane Vignettes in Switzerland, require crossing a narrow icy stone bridge to a cliff, where a cubicle has been carved out of stone and a gaping hole looks down hundreds of metres to the glacier floor.

Each hut has a warden, usually a mountain guide and often something of a character, as befits this lighthouse-like existence. Pampered tourists may find entering a hut akin to being sent to an English public school. All skis, packs and, yes, even your ski boots must be left in an unheated outer chamber. Felt slippers are provided. Take what you need from your rucksack and put it in straw baskets in the common room, the only room in the hut with heating. Here you eat. You can buy as much wine, beer, chocolate bars or snacks as you can consume. But for supper you eat what you are served; there are no menu choices. In my experience the food is plentiful and tasty, though simply prepared. Everything has to be supplied by helicopter.

Starting at the top, Italy’s Refugio Capanna Regina Margherita at 4,554 metres at the very peak of Punta Gnifetti is the highest alpine hut in Europe. It sleeps 96, has its own library and doubles as an observatory for the University of Torino. The Margherita hut dominates the Monte Rosa massif spread along the Swiss-Italian border, and draws tourers from Zermatt as well as the nearby off-piste cult resort of Alagna. Accessing the hut is an achievement.

In the same region, above Alagna and accessible only by skis, is my favourite alpine retreat, the charming and enduring Rifugio Guglielmina. Billed as the highest hotel in Europe at 2,880 metres when it was constructed in 1878, the Guglielmina fell into disrepair and in 1994 was reopened as a mountain refuge. Unlike most mountain huts, the Guglielmina has small, private rooms for couples. The food is amazingly good and inexpensive. Huge ceramic ovens heat the public areas, but the bedrooms, cozily decorated in antique wood and chintz curtains, are utterly unheated.

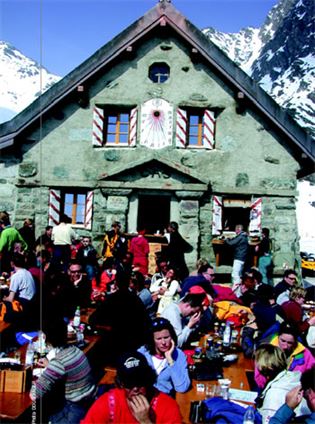

Many huts have taken on a new economic lease on life as lunch spots. As spartan as the accommodation may be, and as cold as the dormitories are at night, these rustic huts draw in tourists at lunchtime when the sun is shining and the views are spectacular. Few huts are near on-piste areas, but several are not far off-piste on well-travelled itineraries such as Chamonix’s fabled Vallée Blanche. Skiers there can sit outside the cramped and smoky Refuge du Requin (the Shark Hut) and marvel at the gaping crevasses and towering seracs just opposite, while chowing down on fondue.

In Saas-Fee the Britannia hut is by night a haven for tourers starting off on the classic Haute Route ski itinerary to Chamonix. But by day it attracts skiers looking for an out-of-the-way lunch venue with some real mountain cred. Verbier’s Cabane Mont Fort, another waystation on the Haute Route, similarly entertains hundreds of recreational skiers on its capacious sun terrace.

Economics and ecology are two threats to the future of the alpine hut network. Most huts date from the early 20th century and some are even older than that. Renovating them can be prohibitively expensive. Other than the spoiled who demand heating, hot water (or any running water at all), indoor toilets and segregated sleeping rooms, environmentalists are attacking the huts as unwarranted carbuncles on the pristine glacier surfaces.

Economics and ecology are two threats to the future of the alpine hut network. Most huts date from the early 20th century and some are even older than that. Renovating them can be prohibitively expensive. Other than the spoiled who demand heating, hot water (or any running water at all), indoor toilets and segregated sleeping rooms, environmentalists are attacking the huts as unwarranted carbuncles on the pristine glacier surfaces.

So skin up this winter (or hike up in summer) while you can. It’s an entrée to the old-school architecture and manners of our skiing forebears, where everyone is equal around the table and in the dormitory, where everyone there has arrived under his or her own steam.

HUT CLUBS

Each of the clubs below has a database of huts with info on how to get there, prices and online reservations.

- The Swiss Alpine Club accepts members who are not residents of Switzerland, and like all the European clubs offers considerable discounts on hut fees to members. The SAC owns some 300 properties, from spartan emergency bivouacs to grand stone mansions with more than 130 “beds.”

- The Austrian Alpine Association (in German) offers its 300,000 members access to more than 1,000 mountain centres in Austria and Germany, many of which are emergency shelters or low-altitude hostels.

- The British branch welcomes Canadians among its 6,000 members, and offers an excellent and inexpensive worldwide rescue and accident insurance package, with no age limit.

- The French Alpine Club (in French only) owns and operates 131 huts. Privately owned huts such as the Refuge des Cosmiques adjacent to the Aiguille du Midi lift station in Chamonix are not listed on the CAF site.

- The Italian Alpine Club (English pages) boasts 23,500 sleeping places in its 763 mountain refuges, 224 of which are emergency shelters.