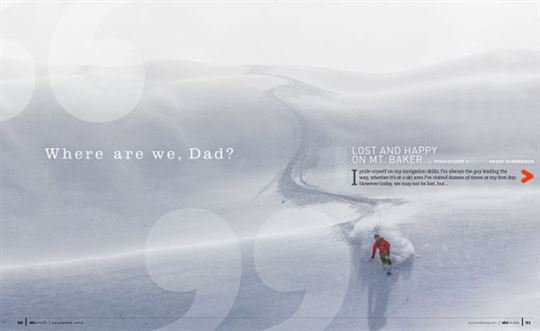

I pride myself on my navigation skills; I’m always the guy leading the way, whether it’s at a ski area I’ve visited dozens of times or my first day. However today, we may not be lost, but…

“Where are we, dad?”_

“Ahhh, I think we just keep going down here,” I stammer and then slide away before my 11-year-old daughter, Paige, has time to question my indecision. The snow’s knee deep and buttery. I whoop as I pop off a buried mogul, submarine into a faceshot and keep on charging.

A minute later Paige slides in next to me, caked in snow to her chest, a white spot where her mouth usually is. Oh, she’s smiling. I smile back. “Where to now?” she asks. Awkward pause. “Dad, are we lost?”

As I peer down the fall line, searching for anything that might orientate me but only finding more massive hemlock trees, untracked lines and fog, both smiles fade. “No, not exactly…”

How can I be lost? This is Mt. Baker, the little big area, just over the border. It’s only 500 hectares. That’s about one-eighth of Whistler Blackcomb. A quarter of Sun Peaks. There are only seven lifts, not counting the two beginner chairs. And the vertical taps out at 500 metres. In numbers, hardly gargantuan.

But I’m realizing that’s the thing about Baker—it’s a bit of a sneaker. It’s like a Jack Russell, small and cute on the surface but all rugged and feisty beneath the facade. Little area, big terrain. A destination hill with a local feel.

Take the approach. We’d driven to Baker from Vancouver that morning. On Google Maps it looked straightforward: kitty-corner across the Lower Mainland via a couple options, slip south of the border, weave through the Washington State countryside and then switchback up to the resort. Just don’t forget about the Vancouver traffic, the border crossing and the seriously curvy road. Even though it was two hours, the drive felt like a journey.

It’s snowing hard as we suit up and walk past three rows of cars to the main day lodge. The quiet slopes work for us. Our first run from the top of Chair 8 down Daytona is almost untouched. It’s 10:00 a.m. I love mid-week. For the next two hours we play in the rolling intermediate terrain on the White Salmon side of the mountain, diving through small groves of trees, plunging off the convex rolls and spraying snowy contrails with every turn.

This is not unusual weather. Baker owns the record for the world’s greatest one-year snow total, more than 29 metres in 1998-99. Even in the mediocre winter of 2016 it collects more than 15 metres of snow, a metre less than average. Among powderhounds it’s known for its massive dumps, amazing tree-skiing and limitless backcountry.

Thoroughly tired and wet, we slide down to the Raven Hut. Like the main White Salmon Day Lodge, it’s a nice open, timber-frame lodge, cozy and welcoming. A few dozen locals sit around the river rock fireplace, drying gloves and jackets on hooks. We find a table, shake off our jackets, helmets and gloves and stomp over to the canteen.

A few minutes later we’re waddling back, our trays overloaded with massive portions of burgers and delicious chowder. Thoroughly stuffed, we head back out into the growing blizzard and shuffle over to Chair 4.

A deep ravine divides Baker in two: White Salmon and Heather Meadows. We spent the morning on the former and now we’re heading toward Heather Meadows. It’s even quieter over here. I chase Paige through a roller-coaster line in the trees and then she follows me down a steep pitch of bumps back to the lift. We lap Chair 4 until a sucker hole in the storm teases us up Chair 6. Near the top of the ride, the lift pops above the surrounding old-growth forest and we’re suddenly blasted by the wind. We huddle together. The clouds descend.

By the time we get off, we can’t see much. A few pitches later I’m contemplating the longer than expected run. When Paige catches up, she must sense my unease. She asks me where we are and I don’t have a good answer. We keep skiing down—I figure we have to hit a run eventually. Just before I start to panic, we do.

Soon after, Paige’s legs give out. I send her down to the car and race off for a couple more laps. For the first time all day, I ride the chair with a stranger: a veteran local. He tells me this is a pretty quiet powder day.

“Baker used to be off the radar, but it’s getting known now,” he says. “People are watching the forecast. When it dumps, they come from all over.”

Today, it feels like a locals hill, mellow, friendly and eclectic. The lifts are newish quads, but they’re all fixed grip. The lodges are modern, but not fancy. There’s no on-hill accommodation, but anyone can camp free. The parking lot’s paved, and campfires are allowed if you make them in the snowbank.

Baker’s incongruity makes more sense when I learn the resort is owned by 250 shareholders, mostly skiers from nearby Bellingham, Washington. That’s the last thing the local tells me as we slide off the lift. Just before he disappears, he looks over his shoulder and beckons me to follow. I chase after him as he leads me into the woods and down a cliff-studded face. Three turns in and I have no idea where I am. Again. As a pillow drop ends in an explosion of white, I realize, for the first time all day, I don’t care.