The jagged Andean peaks of Portillo and the mysterious volcano of Corralco are a unique combination of what South American skiing has to offer.

by George Koch Photos Liam Doran in the Buyer’s Guide 2017 issue

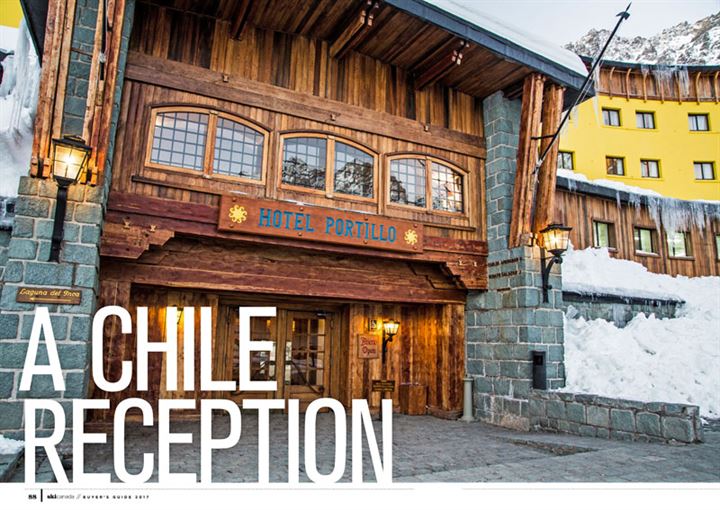

A culpeo lolled on a sun-heated boulder in the afternoon glow, stretching and displaying its glossy grey fur as it turned indulgently for all to see from the chairlift overhead. The lazy Andean fox reflected my own smug contentment midway through a week experiencing the sybaritic pleasures of the Hotel Portillo in Chile, its private ski area and the 2,000 vertical metres of Andean relief reaching from the shores of the bottomless (I’m told) sapphire Laguna del Inca, past the bright yellow hotel and far above the lifts toward some of South America’s highest mountains.

On my right sat Julio Bouchon, a Chilean winemaker producing carmenère and other vintages from his family’s vineyards south of Santiago, the capital. On my left, an Argentinean beauty from Mendoza who appeared to be descended directly from Inca royalty. Both zoomed off expertly in opposite directions at the top of the lift, Julio’s headband-clad head swivelling back as he urged me to buy his wines.

I chuckled at the easy companionship of this singular ski resort, where strangers from around the globe or just down the road behave like old friends. Where world-famous freeriders bring clients for extreme camps, and a long-time local ski instructor plays the accordion while gliding along a groomed run. What was it? I wondered. The surreal ambience of this world-unto-itself? The staggering scenery and rarefied air? The guilty pleasure of skiing at the height of the North American summer? I shrugged and set off down the long Juncalillo run for some more fast carving down corduroy that at 3:00 p.m., with so few to share the world with, was virtually unchanged from the 9:00 a.m. lift opening.

‘‘The surreal ambience of this world-unto-itself? The staggering scenery and rarefied air? The guilty pleasure of skiing at the height of the North American summer?’’

Changing seasons and hemispheres to ski did make Chile seem a world away. Yet in some ways the trip down last August proved easier than going to Europe. I rendezvoused in Houston with three friends: pro skier Sven Brunso, photographer Liam Doran and freeskiing diva Amie Engerbretson. We flew overnight non-stop to Santiago, and the time difference from Toronto was only one hour, so we arrived rested and ready to feel snow under our feet that same day.

Aboard our transfer van, we zoomed along an excellent freeway. The Andes appeared abruptly as a giant wall pierced by a precipitous gorge. Mountains rose 1,500-3,000 metres over our heads. Suddenly the early Chilean springtime gave way to snow and, after steep switchbacks, we pulled into the heart of an Andean ski season.

Portillo’s lifts scale snowfields underlying huge rockwalls to either side of the hotel. Both sides offer a mix of groomed runs, North American-style steeper terrain that gets carved into chalk or bumps, and real off-piste that can hold powder for days, even weeks.

“We’ll take the Plateau quad and head for the Lake Run,” veteran-visitor Sven declared. Despite several days’ worth of tracks, untouched powder remained throughout this varied descent. It opened with rocky gullies spilling into a broad double-bowl, then rolled to ramp-like slopes screaming toward the lake or cliffing out. Last summer, the lake’s waters remained open, and in the past the Lake Run was no-go until freeze-up. Thanks to the catwalk recently hacked through the cliffs, one can enjoy this doubling of terrain all season long. Okay, so maybe I was feeling the altitude just a bit (the top lift pops just above 3,300 metres), for the prospect of pitching over the low guardrail and tumbling 100 metres made me a tad queasy.

After nearly three hours of nice powder, we skated up to the hotel’s skier entrance, ditched our gear and began to revel in the hotel’s multifarious luxury. The self-contained operation for 450 guests has everything from a bar with live music to a workout gym to spacious outdoor hot pools. The ’60s-era French-mountain-style décor has grown a bit worn, but in a genteel way. The recently renovated rooms, though on the small side to North American standards, are elegant with a Euro-chic look plus folk touches like Andean wool blankets.

The next morning the lake sparkled and the sky was the lovely blue called celeste in Spanish. Today it would be straight for Portillo’s best terrain, via the world’s oddest lift: the Roca Jack slingshot.

We each grabbed one of five little platter-style attachments dangling from a horizontal metal bar, the liftee bellowed “ready” in Spanish and the thrills began as we accelerated to 50 km/h up the rough icy track, nearly ejecting from our bindings as one person’s skis clashed with another’s. The liftee standing half-a-mile downslope slightly misjudged our stop, ramming us into the ice wall above the small exit platform hacked into the 40-degree slope that avalanches frequently enough to keep the lift from being replaced. We managed to hop laterally and skitter off without incident. Having mastered the Roca Jack, Portillo’s three other slingshots would be a snap.

The 700 metres of lift-served vertical below us were dwarfed by another 1,200 vertical metres of slopes and cliffs rising overhead. Multiple bowls, open slopes, aprons and cliffy gullies spilled about in plain sight. Yet plenty of untracked remained. As I followed Sven, Liam and Amie through a succession of distinctly sporty traverses, including refrozen no-fall zones threading through cliffs, I began to see why. But the rewards were intense. We shot through an icy choke into a huge bowl crowned by a crescent of cliffs and rolling virtually untracked to the lake.

The next lap opened with a 70-minute stair-climbing session 40 degrees straight up into the area known simply as the “bowl above the Roca Jack”. It was also amply worth it. From halfway up I could see 6,962-metre Aconcagua, South America’s highest peak. Even better was the powder still lying in the bowl’s shaded portions. These were the turns of the trip: thigh-deep blower for 700 vertical metres.

The subsequent skiing days became an enjoyable rhythm of fast morning carving off the Plateau chairlift, followed by a few laps of steep bumps or chalk off the slingshot lifts, a late lunch in the Tio Bob’s alpine restaurant, some cut-up powder or softpack off the Roca Jack, and successive screamers down the Juncalillo or a furtive sneak onto the deserted Descenso, where the Austrian men’s downhill team was training, before the 5:00 p.m. closing bell. Life in late August doesn’t get much better.

————

An hour-long flight southward brought us to the mid-sized city of Temuco. The two-hour transfer to Corralco led past lush pastures and orchards in the lovely Araucania region. After the ramshackle town of Curacautin, the road narrowed then climbed through valleys holding small tin-roofed houses and sagging barns. Suddenly the valley opened and two gleaming-white conical volcanoes rose dramatically to either side.

The brand-new 60-room Hotel Corralco sits where thick forests of Chile’s beloved araucaria pine, or “monkey-puzzle” trees, give way to flat open snowfields sweeping toward the enormous Lonquimay Volcano. Perhaps the hotel architect was trying to mimic the vastness of the volcano’s treeless flanks, for there was nothing but sprawling space throughout the hotel. Minutes later I was sitting beside a roaring fire in the opulent lounge gazing up in awe. From Lonquimay’s flat-topped caldera, ramp-like slopes virtually free of cliffs or rocks dropped at a perfectly skiable 25 to 40 degrees for 1,500 vertical metres.

“You can ski in almost any direction from the top,” commented J.P., the hotel’s bearded young ski school director. “Some days you can just decide whether you want powder or corn snow and then pick your slope.” J.P. told us his favourite route was the mountain’s big southern flank, running full vertical to a hidden bowl, returning via a short ascent on skins. “What about avalanche conditions?” I wondered. J.P.’s brow furrowed. “We had one avalanche last season, or perhaps it was the season before, up on top, far from the lifts,” he replied. Avalanche control? J.P. looked at me like I was from Mars. Corralco, we were told, enjoys a particularly stable coastal snowpack.

Just as I was starting to see the hand of God behind this made-for-day-long-ripping terrain, what had been forecast to be a triple-storm delivering up to two metres of powder began coming in as…liquid—and sideways.

Sorely tempted to lounge in the hotel’s luxe spa complex the next morning, we instead grabbed the heavy green ponchos that J.P. and his equally friendly sidekick Javier handed us from underneath their counter, and headed out.

Corralco has just four real lifts and its trail map looks like a mud streak on the volcano’s elephantine flanks. But everything stretched out as we saw it for ourselves. The lifts climbed close to 900 vertical metres beginning with a flat chairlift and ending with a long T-bar reaching within 500 vertical metres of the peak. What looked flat from afar proved inclined just fine for fast carving, while apparently small slopes rendered whole groups of skiers specks. The lifts were old and rickety, but the corduroy beneath our dangling skis was perfect.

Ice pellets bombarded our faces and the worst gusts nearly rammed us into lift towers. Within 90 minutes merely gripping my poles wrung water out of my gloves to dribble up my forearms. I skated as fast as I could along the run-out trail leading to the hotel’s ski/boot room.

After a second morning-long soaking, we relented and headed off to explore nearby Malalcahuello. The village’s mostly well-tended, tin-roofed clapboard houses made it look more like a Montana ranching town than rural Latin America. With its friendly locals, several small restaurants and bars, plus a swank hot springs resort in a pretty valley nearby, Malalcahuello was charming despite the damp and drizzle.

Meanwhile, up on the mountain the temperature was easing down, transforming driving rain into blizzard. We awoke to snow everywhere, wolfing breakfast and vibrating with excitement as we grabbed our fattest skis and piled into the shuttle van for the three-minute ride to the base. “I think we’ll be skiing by feel,” smirked Sven as we slid off the upper chairlift and arced the day’s opening tracks beneath the empty chairs of the main lift. The dense chowder was like skiing on cream and tentative opening turns quickly gave way to big GS rippers, cries of joy ringing out as we sank our edges in hard and let go.

We vaguely sensed there was a large open bowl beneath a big convex roll between the upper chairlift and the long lower T-Bar. But how far to ski down? Where to cut back? Would anything slide? A sucker hole appeared in the blizzard and we ventured on out. A few turns in eased our fears. The entire mountainside was coated in the same wonderfully skiable smooth blanket. Equal parts Alberta’s Castle Mountain and Alaska. We were the only skiers to leave Corralco’s marked pistes all morning.

The light was much better the next morning and although the snow had densified further, freeride skiing was as simple as turning off the groomers and experiencing the subtle though endless variety of the volcano’s innumerable folds, indents and bulges. The views were stunning: massive white slopes overhead, rounded tree-clad mountains resembling the B.C. Interior receding eastward, jagged glaciated Andes peaks far to the north, and the massive Llaima Volcano flashing into and out of view to the south as the wind hurled about slate-grey clouds. Our world seemed to comprise veritable lifetimes of epic skiing.

Further days of high winds, fog and damp kept us from attempting the Lonquimay’s peak, any touring or even some of the more remote off-piste, and we boarded the minivan for Temuco with disappointment. Back home we learned that just two days later, the weather broke and an American couple we had met were the first to summit. Though I drooled at their wondrous account of a vertical mile of wide-open, big-mountain skiing in smooth corn snow, I felt destined to be back in Chile before long, for Chile had wormed its way into my heart and soul.

If you go

HOLA, HOTEL: Hotel Portillo (skiportillo.com/en) provides complete packages (be sure to ask for a renovated room when you book), including three meals a day plus afternoon tea, overseen by a tuxedoed maître d’ and served by red-jacketed waiters à la 1920s Europe. The brand-new Hotel Corralco (corralco.com) is more informal, like a lodge in North American ski country, with sprawling rooms featuring king-sized beds and ultra-modern baths.

SALUD, SANTIAGO: Chile is no Third World country, and friendly locals eagerly welcome North Americans. If you’re in Latin America for the first time, a sojourn in the capital city is a must. Try the Hotel Singular (thesingular.com). This urban boutique hotel has a rooftop bar and sits in Santiago’s heart with the historical Santa Lucia park, the national museum of modern art, the main city square and the bohemian Bellavista district all within 5-15 minutes’ walk.

TACOS, WHAT TACOS? You’re unlikely to eat much made from cornmeal in Chile. The “national” dish is a juicy medium-rare steak topped with fried onions and an egg fried sunny-side up, all draped over a huge mound of crispy French fries. That artery-clogging combo is the exception, however, for Chile’s cuisine is shaped by the plethora of fresh vegetables, fruits and seafood produced by this incredibly fertile country’s soils and waters. You can expect great food everywhere you go—plus wines from more than 20 locally grown grape varietals.