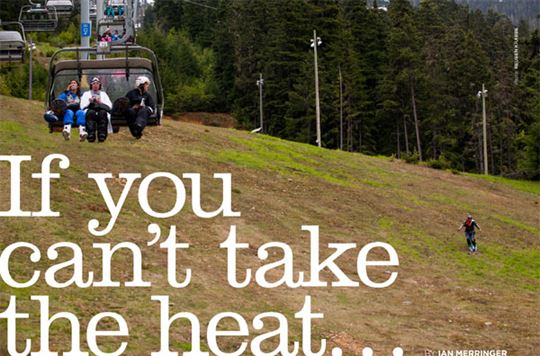

…get out of the ski industry.

With climate change now out of the realm of the theoretical, ski resorts are adapting in different ways.

by IAN MERRINGER in the Buyer’s Guide 2017 issue

High in the Swiss Alps above Andermatt, crews are getting ready for another ski season. The jobs are many. Straightening a few signs, inspecting lift cables and unwrapping the glacier—the job no one wants. Since 2005, the Gurschen Glacier has spent summers wrapped in 3,000 square metres of reflective foil to help keep warming alpine temperatures from making Swiss cheese of the ice sheet. Folding a tarp that large isn’t easy, but it’s part of the response the ski industry is being forced into in the face of a changing climate.

Last year was the warmest ever recorded. Fifteen of the 16 warmest years on record have occurred since 2001, according to one crackpot conspiratorial organization, the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The stakes appear high for an industry built on winter. A U.S. organization called Protect Our Winters commissioned a study from the University of New Hampshire to assess the effect of paltry winters. Researchers looked at resort revenues, skier-visits and employment between 2000 and 2010. Then they compared years with higher versus lower snowfalls.

Over the decade, they found that the U.S. ski industry likely lost $1.07 billion in aggregated revenue between low and high snowfall years. Employment dropped between six and 13 per cent in response to 25 per cent fewer skier-visits. After last winter’s meagre snowfalls in the East, Ski Vermont reported a 30 per cent drop in skier-visits compared to the previous year.

Ski resorts will have to learn to live with such statistics, according to David Phillips, senior climatologist with Environment Canada. “There is no question, the numbers are clearly there. It’s not a futuristic thing or something happening somewhere else. It’s here and now,” says Phillips.

General planetary disruption aside, skiers have some particular things to fret over, namely that the warming occurring in Canada is being felt mostly during the wintertime and at night.

“The old-timers are right, winters aren’t what they used to be,” says Phillips, adding that over the past 70 years Canadian winters have become 3.3 degrees warmer, with the other three seasons only registering increases of 1.6 degrees.

Likewise, those warmer values are registering not so much as warmer days, but as nights that are not as cold.

Phillips notes that data for Ottawa shows that compared to 70 years ago, daytime temperatures have risen by 1.5 degrees but nighttime temps have risen by almost three degrees. That adds to the challenge for a ski industry that takes advantage of cold nighttime temperatures to blanket resorts in artificial snow.

Of course, skiers in the West are probably still feeling burning thighs after a 2015-16 season that made El Niño come across as a fun little guy. If there is a new normal to expect, says Phillips, it may be volatility. Even as resorts in Quebec’s Eastern Townships were receiving half their average annual snowfall last season, for instance, ski areas across the West were getting enough snow to make them forget that a year earlier resorts like Castle Mountain and Mt. Washington had simply closed mid-season due to lack of snow.

Last year across Canada, every month was warmer than normal. The previous winter, Eastern Canada was one of two places on earth that was colder than normal.

“There has always been volatility,” says Phillips, “but now it’s a Jekyll and Hyde situation where outliers occur more frequently. According to Phillips, a possible explanation is a jet stream that’s in flux, where the upper-atmosphere air current that flows generally west to east across mid-North America has slowed by 15 per cent in the last decade. It’s also gotten loopy, looking more like a roller-coaster track at times, with swings to the north and south. The effect is not just weather that doesn’t conform to historical norms, but weather systems that sometimes get slowed and blocked in their paths, inundating one area and bypassing others.

********************************************************************************

“Expect the unexpected,” says Phillips.

The expectations of skiers are always on the mind of Matt Mosteller, senior vice-president of marketing, sales and “resort experience” at Resorts of the Canadian Rockies (RCR), owner of six major ski resorts, including Fernie and Kicking Horse in B.C. and Quebec’s Mont-Sainte-Anne. “We look to the future and ask ourselves, ‘What sort of offering should we provide?’”

Mosteller says that in part because of vacation trends and in part because of “climate reasoning,” the resorts are moving ever more toward expanding their activities: “The mountain lifestyle experience is becoming a basket of things.” Before high-speed quads were prevalent, après ski meant going to the bar; there was no time for anything else. Now, he says, after reaching a vertical limit you might quit early and still have time to do something different, so resorts are offering things like fat biking, via ferrata courses, ziplines and aerial activities.

This, of course, makes the idea of a ski holiday more resilient to less reliable weather, and it’s a strategy being followed across the industry.

This spring, Whistler Blackcomb announced plans to build a 15,000-square-metre indoor water park featuring waterslides, a surf simulator, rock climbing, a wave pool and bowling.

Similarly, Mont Tremblant spokesperson Annick Marseille says prospective visitors should remember, “Tremblant remains a resort, even if our winter operations are mainly related to skiing.” She points to a lively pedestrian village, ceramic painting, yoga, deck hockey, music shows, karaoke, hiking, shopping and mini golf (not to mention a casino) as activities that helped Tremblant weather a Christmas break last season that saw temperatures near 20 degrees.

As far as on-hill adaptations go, many resorts are responding like SilverStar near Vernon, B.C., and investing in not just snowmaking but also increased summer grooming, to give the early snows of winter a head start in burying the alders. Director of Operations Brad Baker says that on the steeper runs where they can’t get power mowers, they send saw crews in on foot every two years. With this new type of grooming, they can open most terrain with as little as 30-40 cm of snow. They are also starting to glade new runs instead of clear-cutting them, to retain partial shade and prevent wind losses.

As for reducing greenhouse gases, many resorts claim to have reduced their carbon footprint through upgrading their snowmaking equipment, vehicles and lighting. Grouse Mountain built a wind turbine, but it hasn’t released output numbers.

None has gone as far as Whistler Blackcomb, which in 2010 partnered with a utility to build a run-of-river hydro plant on Fitzsimmons Creek, between the two mountains. With a capacity of 7.9 MW, it’s estimated to offset 100 per cent of the resort’s annual energy needs. Or present needs anyway. Alpine countries are quickly learning that as glaciers shrink and spring snowmelt decreases, so too does the harvestable hydro energy.

Last year marked the first summer season Whistler Blackcomb pumped water onto Horstman Glacier to make artificial snow for summer skiing.

The sanguine skier will probably want to focus less on global warming and more on climate change, and there is reason to hope. Warmer air holds more moisture, which could mean more snow, not less, especially for drier, colder interior areas like the Rockies.

“We’re not thinking doom and gloom by any means,” says Brian Rode, vice president of marketing and sales at Marmot Basin. Rode notes that the Jasper, Alberta, ski resort is in the northernmost area of the Rockies with the highest base elevation in Canada and concludes, “Our geographic location puts us in a better position than most areas. We never see rain in the winter. A little warmer for us doesn’t mean melting, it means really nice skiing weather. ”

Michael Ballingal, sales and marketing manager at Big White, provides snow data for the last 34 years and points out that the Okanagan resort has received more snow over each of the past two decades than it did between 1986 and 1996.

David Phillips says that the popular Collingwood area north of Toronto, which can’t rely on elevation to suck snow from the sky, could see an increase in lake-effect snow if warmer temperatures keep more of Lake Huron from freezing for longer periods in the winter.

Finally, there’s always the possibility that climate change will be an unprecedented boon for Canadian ski resorts, with no more effort necessary than the shifting of marketing dollars to start luring nervous Americans. If more southern resorts in the U.S. start to look like gambles, Canadian resorts will appear comparably reliable, even in an otherwise uncertain climate.