Austria’s massive Gastein Valley has four distinct ski areas, thermal baths for whatever ails you – and a 2000-year-old tourist office

by George Koch

Holy smokes, there’s two of you, I better get this unit fired up.”

The cavernous cable car—made for 80—held one other guy. I’d just finished railing a groomed run that ringed a distant peak dropping 1,000 vertical metres on pristine corduroy just starting to soften into corn. Devoid of others. A tough snow year meant the large, well-developed resort of Badgastein in Austria’s charming Salzburg province was struggling. Sad for the resort; all to the advantage of the few skiers. I’d cruised from Badgastein up the valley to the Bad Hofgastein area, poking around there before taking the area’s signature Hohe Scharte descent. The ultra-modern lifts were essentially my private conveyances, and the marked pistes were as well-covered as they were fantastically buffed. And thanks to our cheerfully sarcastic liftee, even the empty cable car swooped up the mountainside as soon as two skiers stepped aboard.

This was my third visit to Badgastein. It’s one of the many lower-lying, statistically-not-that-impressive resorts in the Austrian Alps frequently overlooked by North American number-junkies who think good skiing in the Alps starts at 3,000 metres. Austria’s lower-lying places ski very well, especially in mid-winter when treed terrain and warmer elevations are welcome. Take our visit three seasons ago to Serfaus in Tirol province (SC, December 2009), where we had days of epic peak-to-valley powder.

Of course, last season the stat-junkies would have to be right. By my early-April visit, Badgastein’s lower slopes were bare and the valley was green. It seemed almost a waste to return to the resort that, 31 seasons previous when I was a sprout of 17 and away from home for the first time, had stirred what blossomed into my enduring love for the Alps. A two-day blizzard had left 80 cm of what we today call “blower,” and I took my first major off-piste run—a side valley off the same Hohe Scharte I mentioned earlier. This time, entire mountainsides were unskiable, and my companions—veteran ski photographer Henry Georgi and ace pro riders Sven Brunso and John Trousdale—could only speculate about what we’d find with a decent base and a foot of fresh. Yet, each day our skiing proved far better than expected.

Despite its state-of-the-art lifts, Badgastein is no latecomer to tourism. One of the world’s first tourism destinations, its thermal baths were famous in Roman times 2,000 years ago. Ancient gold-mining shafts, hacked out of the granite over the eons, run for miles through entire mountains. The valley flourished during the European upper-class tourism flowering

through the 19 th century, and today the stately and beautiful Victorian-era architecture remains the main town’s signature look. The pretty agricultural valley of multiple villages holds thousands of guest beds and every variety of restaurant and bar.

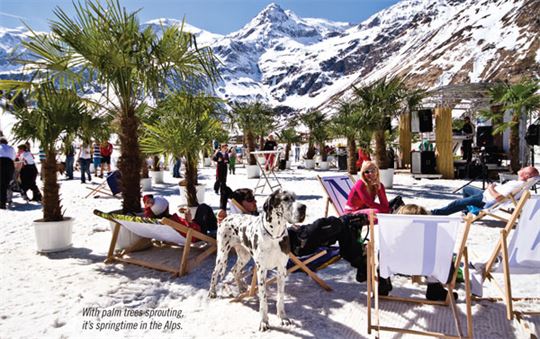

Today’s tourism clientele is worldwide, including hundreds of young Scandinavian ski bums who come, if not exactly for the waters, then to party, hook up and shred pow. Many older tourists come for the thermal baths and the bizarre practice of lying down in old mine shafts to soak up radon. I’m not making this up. According to its followers, this stuff is “scientifically proven.” I guess once your knees have given out and you no longer ski avalanche slopes at hazard level 5, radon provides that frisson of living on the edge.

The four of us spent much of our skiing time at Sportgastein, the highest-situated and snowiest of the valley’s areas, a 20-minute bus ride from the main village, and close to the Italian border. The 1,100 vertical metres accessible through a single gondola ride and the mountain’s unique convexity create a vast adventureland. The frontside holds phenomenal carving pistes plus easy-access near-piste. The views are estimable: rank upon rank of craggy peaks rising in vaulting relief, reminiscent of Switzerland’s storied Valais area or the French Alps.

Klaus, a young ski instructor, showed us around the mountain’s southern and western flanks of vast, snow-covered slopes dropping into a flat treeless valley swinging back to the gondola. Lap after lap we pointed our skis almost randomly and headed down. There’d been a nighttime freeze, the sky was a dazzling cobalt and the slopes were softening into delectable spring corn snow. Some laps we’d veer sharply rightward and make it back to the midstation. Others we’d head down some gully or shoulder to the valley floor and then push/skate 20 minutes to the base.

Sportgastein’s classic descent is simply called Die Nord, the North. It’s a huge, marked but uncontrolled, north-facing cirque with multiple routes dropping nearly 1,500 vertical metres to a bus stop on the access road. The northerly aspect wasn’t powder, nor quite corn, but it was skiable as a kind of semi-softened, semi-hard surface. While Klaus and I chose the fairly steep Gummirinne, or Rubber Gully, Sven and John hiked up from the frontside to the formidable Salesenrinne. As he started his descent, Sven spooked a massive grazing bull ibex, which hurtled down the fall line Sven was trying to ski before veering off onto some rocks. Tough to say whether man or beast was more surprised.

Most winters we could have skied right to our accommodation, as we were housed at an out-of-the-way establishment on the Sportgastein access road. The Hotel Evianquelle has a charming setting beside a rushing brook, with a beautiful natural spring of pure mountain water feeding trout ponds in the front yard. One night the owner served delicious freshly netted, pan-fried brook trout. The hotel also had a great sauna downstairs. Unfortunately, the guest rooms were straight out of the ’70s, the bathrooms were tiny and the beds were old. Just not the right place for Canadian destination travellers. Klaus instead recommended Haus Hirt, lying above Badgastein, saying it has a beautiful modern design, fully renovated rooms, a superb kitchen and a free shuttle bus.

Our funkiest evening was in an out-of-the-way village down the valley. We exited our rented car in front of the Unterbergerwirt to the tangy aroma of agriculture in springtime. Two little cats greeted us on the landing and inside was a lovely heritage dining room, what the Austrians call uhrig. Owners Hanz-Peter and Elfriede Berti served a series of delicious locally raised organic dishes. Elfriede is also a prize-winning chef of the Salzburger Nockerl, a soufflé-like dessert invented for an 18 th-century Austrian empress. I hadn’t had one in 30 years because I invariably say, “I could have this anytime,” and then I never do. Elfriede’s creation was sublime—literally the size of our heads—and we devoured it in moments.

Despite the challenging conditions, our visit yielded one phenomenal off-piste adventure. Sportgastein looks across at a stupefying mountainside that opens with a sheer, 40-plus-degree face dropping 1,000 vertical metres: the east flank of the infamous Schareck. After benching out in a broad bowl, the descent continues another 500 vertical metres with a rollaway slope ending in cliffs, then a 45-degree offset couloir to an exit trail. I’d spent hours ogling it on my last visit in 1997. My guide, Andreas Krobath, had said you could step right in from an unseen chairlift at a distant ski area, the Moelltaler Glacier. The Schareck never left my to-ski list.

Klaus’s boss, famous mountain guide Gerhard Angerer, met the four of us early on our last morning at Badgastein’s railway station. The train took us beneath the mountain and we exited in the neighbouring province of Carinthia. We boarded an underground funicular at the Moelltaler ski area, then rode a chairlift. Next thing I knew we were at 3,100 metres walking past the ubiquitous Austrian mountaintop cross, then peering between our ski tips down an almost indescribably big face. This would be a no-mistakes undertaking.

Sven pushed off and within seconds was reduced to a speck. I felt like an ant. After skittering in the icy entrance, I made a cautious hop-turn and came down in delicious, soft winter snow. I let my skis run and the fun began. As the vertical metres ticked away, winter snow gave way to crisp corn. The slope ran and ran—each of us had a personal fall line 50 metres wide. The run of the season, if not the decade. Down in the bowl I came upon three Swedish ski bums sunning themselves on a rock and sipping beers. In my best Swedish I inquired if they knew the way to the Swedish government liquor outlet; they roared and passed me a tin. Later on, riding up the Sportgastein gondola, our entire descent unfolded like a vast diorama, and a lone eagle soared in grand circles over the scene.

For our last day in Austria, I’d planned a little side adventure to scout Carinthia, rumoured also to have fine skiing. We stayed in Mallnitz, the staging village to the Schareck, in a wonderful small hotel, the Sonnenhof. The proprietor, Erich Hohenwarter, proved a singular character, evincing a fierce commitment to “zero km” gastronomy. He fed us an amazing spread of locally raised lamb, organic vegetables and local goat cheese—plus a locally distilled herbal schnapps. A great way to spend a rainy and otherwise depressing evening, for it wasn’t clear how high the snowline was.

The next morning we met local ski instructor Patrick, who drove us to a creaky-looking pulse lift. Two lift stages and nearly 1,500 vertical metres later we were atop a snow-pummelled peak, the Ankogel, staring into an enormous basin blanketed in boot-top powder. Literally not another soul was stirring. From depression to “Game on, boys” in 30 seconds. Lap after exhilarating and eventually exhausting lap of untracked April powder. The Ankogel and the surrounding mountains really reminded me of B.C.’s Purcells—other than that the lower valleys were already verdant with apple trees in full bloom. It made for a magnificent if reflective drive back to our waiting Swiss airlines flight in Zurich—and our return to reality.

GO GASTEIN

1,850m vertical, 44 major lifts, 200kms of groomed, marked runs, 17,000 beds (up to 5-star), dozens of bars, restaurants, clubs, spas, radon caves, historic villages, fly fi shing…

www.gastein.com

guiding: www.ski-alpineschule.at

❄