by Pat Lynch in the December 2012 issue

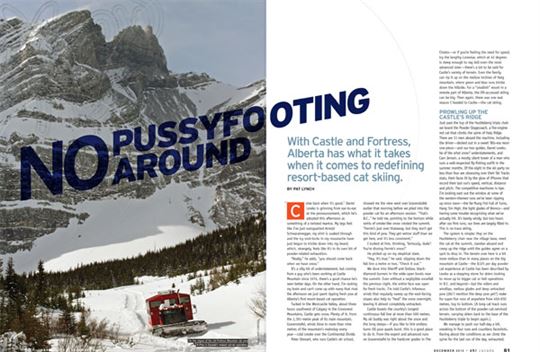

With Castle and Fortress, Alberta has what it takes when it comes to redefining resort-based cat skiing

Come back when it’s good.” Darrel Lewko is grinning from ear-to-ear at the pronouncement, which he’s adopted this afternoon as something of a twisted mantra. My legs feel like I’ve just outsquatted Arnold Schwarzenegger, my shirt is soaked through and the icy snot-locks in my moustache have just begun to trickle down into my beard, which, strangely, feels like it’s in its own bit of powder-related exhaustion.

“Really,” he adds, “you should come back when we have snow.”

It’s a silly bit of understatement, but coming from a guy who’s been working at Castle Mountain since 1974, there’s a good chance he’s seen better days. On the other hand, I’m racking my brain and can’t come up with many that rival the afternoon we just spent ripping fresh pow at Alberta’s first resort-based cat operation.

Tucked in the Westcastle Valley, about three hours southwest of Calgary in the Crowsnest Mountains, Castle gets snow. Plenty of it. From the 2,391-metre peak of its main mountain, Gravenstafel, winds blow in more than nine metres of the mountain’s mainstay every year—cold smoke over the Continental Divide.

Peter Stewart, who runs Castle’s ski school, showed me the view west over Gravenstafel earlier that morning before we piled into the powder cat for an afternoon session. “That’s B.C.,” he told me, pointing to the horizon while swirls of smoke-like snow crested the summit. “Fernie’s just over thataway, but they don’t get this kind of pow. They get wetter stuff than we get here, and it’s less consistent.”

I looked at him, thinking, ‘Seriously, dude? You’re dissing Fernie’s snow?’

He picked up on my skeptical stare.

“Hey, it’s true,” he said, slipping down the fall line a metre or two. “Check it out.”

We dove into Sheriff and Outlaw, black-diamond burners in the wide-open bowls near the summit. Even without a negligible snowfall the previous night, the entire face was open for fresh tracks. I’m told Castle’s infamous winds that regularly sweep up the east-facing slopes also help to “heal” the snow overnight, leaving it almost completely untracked.

Castle boasts the country’s longest continuous fall line at more than 500 metres. My ski buddy was right about the snow and the long steeps—if you like to link endless turns till your quads burst, this is a good place to do it. From the expert and advanced runs on Gravenstafel to the hardcore grades in The Chutes—or if you’re feeling the need for speed, try the lengthy Lonestar, which at 42 degrees is steep enough to rag doll even the most advanced skier—there’s a lot to be said for Castle’s variety of terrain. Even the family can rip it up on the mellow inclines of Haig mountain, where green and blue runs trickle down the hillside. For a “smallish” resort in a remote part of Alberta, the lift-accessed skiing can be big. Then again, there was one real reason I headed to Castle—the cat skiing.

PROWLING UP THE CASTLE’S RIDGE

Just past the top of the Huckleberry triple chair we board the Powder Stagecoach, a fire-engine red cat that climbs the spine of Haig Ridge. There are 11 men aboard the machine, including the driver—decked out in a sweet ’80s-era neon one-piece—and our two guides, Darrel Lewko, he of the what snow? understatements, and Cam Jensen, a mostly silent tower of a man who runs a well-respected fly-fishing outfit in the summer months. Of the eight in the ski party no less than four are obsessing over their Ski Tracks stats, their faces lit by the glow of iPhones that record their last run’s speed, vertical, distance and pitch. The competitive machismo is ripe. I’m looking east out the window at some of the western-themed runs we’ve been ripping up since noon—the far-flung Fist Full of Turns, Hang ’Em High, the light glades of Bronco—and having some trouble recognizing what we’ve actually hit. It’s barely windy, but two hours after our first runs, our lines are largely filled in. This is no-trace skiing.

The system is simple: Hop on the Huckleberry chair near the village base, meet the cat at the summit, clamber aboard and creep up the ridge until the guides agree on a spot to drop in. The terrain over here is a bit more mellow than in many places on the big mountain at Castle—the $325 per day powder cat experience at Castle has been described by Lewko as a stepping stone for skiers looking to move up to bigger cat or heli operations in B.C. and beyond—but the rollers and windlips, mellow glades and deep untracked pow (did I mention the deep pow yet?) make for super-fun runs of anywhere from 450-650 metres, top to bottom. (A long cat track runs across the bottom of the powder-cat-serviced terrain, carrying skiers back to the base of the Huckleberry triple to begin again.)

We manage to push our half-day a bit, sneaking in four runs and countless faceshots. Raving about the conditions as we climb the spine for the last run of the day, exhausted, sweating and laughing all the way, Lewko starts in on his snow-fail mantra.

“Guys, I wish you coulda seen it when the snow came down last month.”

The cat bursts out in incredulous laughter. We’ve been throwing up huge roosts run after run all afternoon. The snow has been fantastic.

“Seriously,” he says, grinning. “You really gotta come back when the snow’s good.”

Done deal, Darrel.

CLAWS OUT IN KANANASKIS COUNTRY

By the time I get to the gates at Fortress Mountain Access Road, the K-Pow powder cat is already packed and prowling the slopes. It’s supposed to be a four-hour swing up from the Westcastle Valley to Kananaskis Country, where Joey O’Brien and his crew run Kananaskis Powder, aka K-Pow, on the site of Fortress Mountain, but it took a little longer than that, sunshine notwithstanding. Fortress is a place long since a memory for most Calgary locals. After a series of operators tried to make a go of it, the hill’s been mostly decommissioned; many of the lifts have been plucked off the hillsides, and its funky old-school day lodge buried in drifts of snow. There’s a narrow snow-choked road that climbs from the parking lot to the old base, where a smattering of outbuildings and machinery sits in the afternoon sun.

The hill itself may be down, but it’s most definitely not out.

“We’ve been on the project for four years,” O’Brien tells me last Easter weekend. “The sins of our predecessors are what we’re being measured by every step of the way. But we’ve spent almost two-and-a-half years negotiating our licenses. Last summer was the first time we were actually on the ground.”

For anyone who hasn’t been to this part of Alberta before, the ground O’Brien’s talking about is spectacular. With a 2,370-metre, two-mountain summit dwarfed by soaring rock walls, cornices and ginormous bowls, it’s a place that’s so physically dramatic it literally takes the breath away. There’s good reason why Hollywood director Christopher Nolan, who arrived in 2009 to shoot scenes from the Leonardo DiCaprio flick Inception, is said to have leaned over to an assistant on the summit and declared unilaterally: “Cancel Utah.” He’d found his location.

On the day I arrived the Roxy crew was doing a 2013 catalogue shoot in the distance. Transworld, Billabong and Live with Regis, er, Kelly had all been up that season to shoot on location. Seen the Bourne Legacy? Well, then you’ve also had a glimpse at the sprawling alpine epicness that is Fortress.

One day, a new resort will rise from the remains of the old; in the meantime, the hill itself has been open to the public since last January, when they ran the first load of visitors uphill in the K-Pow cat. Since that time, they’ve been pretty much booked to capacity every day they’ve been open (K-Pow only operates four days a week, from January to the end of April for about $375/person).

“For a lot of people, it’s not necessarily the money,” says O’Brien when I ask about the rabid interest. “It’s the time. If you’re in Calgary [Fortress sits about an hour and fifteen minutes to the west], you get up in the morning, come here and ride back home that same night.”

But there’s more to it than finances and convenience.

While the fully loaded cat chugs around the ungroomed pow-laden runs, Chris “Chevy” Chevalier throws me on the back of his snowmobile for a few clandestine sled-assisted runs and a peek at what’s on offer, which is, basically, everything.

From the old South Chutes to the West Woody Ridge and Broken Pole Bowl, wherever you point your finger, the cat can take you there (well, pretty much anywhere; where you ski depends entirely upon the skill level of the gang in the cat and, of course, conditions).

I manage to squeeze in a few mid-afternoon turns down the pristine frontside of the hill in deep powder that holds its own under the late-season sun; these are cut greens and black diamonds with light glades, easy to navigate chutes and even some bumps. Like Castle’s powder-cat terrain, much of the skiing currently on offer at Fortress could be viewed as a stepping stone to bigger, more expensive cat and heli trips.

Chevy, a laidback veteran, who was part of the high-profile exodus of staff from Sunshine in 2010, meets me at the bottom of each rip with the sled, grinning.

“So, think you wanna do another run? I can take ya back up, ya know.”

Hell yes, please.

Chevy drops me back at the maintenance garage where the powder cat is unloading its crew of highly stoked skiers.

“Mind-blowing,” says one.

“The best ski experience I’ve ever had,” beams another. “Never seen anything like it.”

Joey O’Brien soaks it all in as the sun starts to set over the Rockies. His cat operation, officially the second resort-based facility in the province, is proving to be a resounding success. But he’s got plans. Big ones.

“I’d love to have a hybrid resort up here with a maximum of 100 people per day,” he tells me, sounding like an owner of southern-Colorado’s infamous Silverton Mountain. “I’d love to take people on tours; I’d love to have some senior members of the [Canadian Ski Instructor’s] Alliance, the Snowboard Federation or CASI here, giving the level of service I’d love to see. If we could do that, then we’d really establish ourselves in a different position.”

Of course, there are obstacles in the way of all that happening.

But, as he tells me in an email exchange in the fall, change is afoot: “We finally got our pathway for a development permit in June this year. [Five years after starting.] We have engineers, land planners, architects, investors all running around the place.”

The hybrid plan is a ways off, but this winter, there’s going to be cats in them thar hills. Getting to play with one is going to be the trick.

“We’re going to have 1,000 seats available this year,” O’Brien tells me. “We expect to be 100 per cent booked by sometime in December.”

Cat tracks

CASTLE MOUNTAIN RESORT

Location: About 2.5 hours southwest of Calgary, in the Westcastle Valley; nearest town is Pincher Creek.

Lift ticket: $67/day; $325/day for cat skiing (not including GST).

Best knee-shaker: Lonestar, a 42-degree monster with one of the longest continuous pitches in the province.

How to fake it as a local: Disparage Fernie; mumble the words “cold smoke” when nearing the summit; pretend the snow is terrible when it’s obviously amazing.

FORTRESS/K-POW

Location: About 1.25 hours from the west side of Calgary, in the Kananaskis Valley; nearest town is, well, probably Calgary (unless you consider a casino to be homey, then it’s the Stoney Nakoda Casino on Hwy 1).

Lift ticket: $375/day (not including GST).

Best knee-shaker: Ask the dude behind the wheel of the cat; your choices are pretty much up to him.

How to fake it as a local: Constantly refer to the hill as Snowridge, a name for Fortress that will confound anyone under the age of 73; bitch about the regional authorities; yawn near the summit while casually muttering “NBD, dudes, N-B-DEEEE.” kpow.ca