North America’s larger ski resorts are often thought of as cash-generating mechanisms for bloodless corporate interests, but in many cases they’re operated by individuals for whom the mountain is something deeply personal.

by GEORGE KOCH in Winter 2016 issue

Lake Louise, owned by Calgary entrepreneur and former mountain guide Charlie Locke and his family, is in the latter category. For decades Locke has had a vision—when financial circumstances, market demand and regulatory approvals aligned—to expand Lake Louise’s lift-served terrain into several cherished zones within his expansive but largely undeveloped lease. The envisioned build-out would add alpine, transitional and forested terrain for novices, intermediates and experts alike.

Three months before Lake Louise’s early-November kick-off of the 2015-16 ski season, the resort’s formal Site Guidelines were signed by Alan Latourelle, CEO of the Parks Canada Agency, and accepted by the then-minister responsible for national parks (since defeated in the October general election). In a press release, Parks Canada called the Site Guidelines a “blueprint” for Lake Louise’s future development. The Site Guidelines feature some dramatic departures from Locke’s original ideas.

Largely the work of Locke, his wife, Louise, and daughters Robin and Kim, the agreement includes significant new high-alpine terrain, a makeover of the frontside, and key infrastructure such as a snowmaking reservoir and various new buildings. Among the frontside improvements will be greater parking, an additional ticket sales location, a doubling of the beginner skiing area, new sheltered novice and intermediate runs, more commercial space, widening of several narrow lateral runs and greater up-and-out lift capacity.

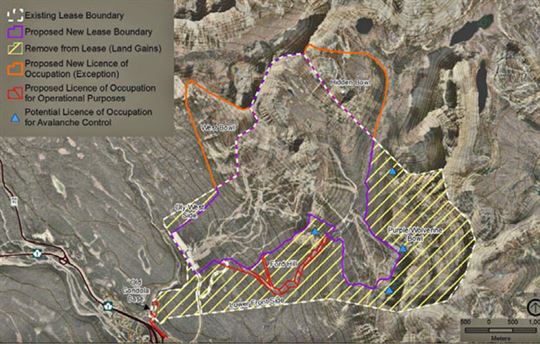

Dumped, however, are long-held plans to build lifts into Purple Bowl, an alpine hike-to area far above the Larch Chairlift, and onto Wolverine Ridge, a mixed alpine and treed area above Temple Lodge. What happened? “We’d been working with Parks to get approval for some of these things since the late ’80s,” says Locke in a conversation during a skiing weekend. “Parks Canada were pretty tough to negotiate with, and they wouldn’t give us everything we wanted.” Robin and Louise, he continues with a chuckle, “brought reason to the negotiating table and compromised where I wouldn’t have. Rather than beating my head against the wall on Purple Bowl and Wolverine, they persuaded me to give up those items.” The upshot? “With this master plan, the hard part of the approval journey is over,” Locke says. “We’re very pleased, and I think skiers are going to love what we do.”

Locke is particularly excited about the new planned alpine expansion into Hidden Bowl. This is an approximately 200-hectare alpine area on the north-facing and leeward side of Richardson Ridge (which is the far rim forming the valley that holds the back bowls). The Site Guidelines call for a lift and warming hut in Hidden Bowl, which would remain natural freeride-style terrain. “Hidden Bowl is as big as all our existing alpine bowls,” Locke enthuses. “It gets loaded by snowfalls. Having that terrain will reduce skier traffic on the other steep terrain, preserving great snow for much longer. With the new terrain, it would take even a very good skier probably three days to ski every line in the ski area once.”

This give-and-take is the basis of Lake Louise’s and Parks Canada’s contention that the plan is a win for skiers, the resort as a business, Parks Canada as a custodian of the environment, and the environment itself. Purple Bowl and Wolverine Ridge, for example, are deemed important mountain goat habitat with significance for the local watershed and cutthroat trout. They will remain pristine wilderness. The snowmaking reservoir is another win-win. It will capture a portion of stream flows during spring run-off and thereby reduce water draws in the late fall when stream flows are very low.

In addition, a planned new lodge atop the Grizzly Gondola on Eagle Ridge will enable the resort to implement a long-held Parks’ demand to close summertime activities around the mid-mountain Whitehorn Lodge. Substantial grizzly bear activity in this area has required placing electric fences from the top of the Glacier Chair to the lodge. Overall, the Lockes surrender 47 per cent of their lease area while adding licences of occupation for limited winter-only activities that reduce their net loss to 696 hectares or 32 per cent.

“We took a portfolio approach to this exercise, and what we’re getting is more realistic and more important to our customers than going into Purple Bowl and Wolverine Ridge,” says Dan Markham, Lake Louise’s director of brand and communications. The overall plan reflects today’s skiing public, says Markham: “Certain resorts pride themselves on 65 per cent black-diamond terrain, while others are basically beginner-intermediate hills. We pride ourselves on having a balance. As we add terrain and lifts, we want to maintain that balance.” Markham also points out that the Site Guidelines are not blanket approvals. “Every single element will have to have an environmental assessment, a financial feasibility study and a long-range planning document requiring Parks Canada’s approval,” he says.

Readers will be staggered to learn that some environmental groups oppose the plan while certain news media did their bit for the green cause. The good old CBC, for example, ran a map showing only the proposed winter expansion area—cutting off the much larger area being surrendered. Kevin Van Tighem, a former superintendent of Banff National Park, declared, “I see a major threat to the integrity of wilderness zoning in all of Canada’s national parks and an unbalanced giveaway of Banff’s ecological well-being to a corporate interest.”

Personally, I would say it’s Van Tighem’s rhetoric that’s unbalanced. When the alleged corporate interest receiving the alleged giveaway consists of a family-run ski area surrendering nearly half its land, within the remainder of which every iota of future development will be meticulously assessed, federal bureaucrats having veto power even over the colour of lodge stonework, the reasonable person may fail to see how this can hasten the extinction of entire species of charismatic megafauna. Lake Louise’s shrunken lease represents 0.17 per cent of Banff National Park’s area.

The plan appears to have reasonable support in Banff. “Skiers and the tourism community are very excited,” Locke says. “Our improvements will really strengthen our ski area’s and the whole region’s ability to draw destination skiers.”

When will skiers see improvements? “It will be next spring before we can put shovels in the ground,” says Locke. “We’ll start with some of the low-hanging fruit, and I suspect we’ll see regular new projects for probably 10-15 years.” One item to be plucked early is West Bowl, a large area to looker’s left of the Summit Platter. This project requires only a stone entry path and an exit trail to be accomplished. After existing for decades as a beyond-the-boundary, ski-at-your-own-risk area enjoyed equally by weed-puffing snowboarders sessioning kickers and old boys on their end-of-day powder run, West Bowl will be fenced, avalanche-controlled, patrolled and subject to closure.

This is the one part of the plan I don’t like. West Bowl is great the way it is. Once it’s part of the ski area, it will likely be among the last areas the patrol opens. But I recognize that in our risk-averse, safety-obsessed era, the West Bowl free-for-all is probably an accident waiting to happen. The resort would receive much of the blame and Parks Canada might then subject this lovely zone to one of its bogus environmental closures.

In the big scheme of things, of course, my West Bowl gripe is a quibble. I think the Site Guidelines will bring decades of added skiing pleasure to untold thousands of individuals and families—without wrecking the national park environment.