Sampling the Okanagan duo of Big White and SilverStar kept Ian Merringer and family well entertained.

by IAN MERRINGER in the Fall 2017 issue

BIG WHITE

Dragon’s inscrutable eyes stared out at us from his darkened lair. Pale and unblinking, they betrayed no hint of his next move. Little else of his coiled body was visible in the dark, but from each nostril a wisp of smoke suggested menace.

Or maybe I could just see his breath on account of the cool weather. Probably water vapour. As it turned out, his next move was to come out of his plywood doghouse and lick my seven-year-old daughter Nora’s hand. She giggled and I moved on to where Diablo and Goblin were chained up in hopes of finding the type of mostly wild, half-breed wolf that I always imagined was the kind of beast needed to pull sleds through a snowy wilderness.

Diablo and Goblin were more indifferent than intimidating. And don’t get me started about Pancake, Snoopy and Sparkle. Duke, I dug, but maybe only because I had once tried to popularize Duke as a nickname for myself.

Clearly my youthful reading of Jack London stories had given me an incomplete picture of sled dogs. These ones were sizable but sociable animals. Each obviously had its own character, but none with a personality disorder sufficient to inspire a short story.

When musher Tim Tedford had harnessed his choice of eight dogs for our half-hour circuit, I was glad to see that Shadow, Ranger and Bandit had made the cut. Proper sled dog names, those.

The dogs that were left chained to their posts joined in a mournful howl as the lucky eight got the command and we lurched down the trail away from the kennel.

Tedford’s dogsled trails are adjacent to others for cross-country skiing, snowshoeing and horse-drawn sleigh tours. The network is just downhill from an ice-climbing tower, tube park, skating rink and track for mini-snowmobiles. Immediately above that complex designed to blow the minds of children is a ski resort. It’s called Big White, which, of course, is very much worth travelling to just for itself.

But Big White and all its attractions is only half the story of a ski trip to the Kelowna region in B.C.’s Okanagan Valley. A similar distance in the opposite direction from nearby Kelowna’s airport is SilverStar, an equally worthy, full-service ski destination with a similarly stocked stable of après-ski activities (just switch out Big White’s dogsledding for SilverStar’s fat biking and bowling).

Or are they alt-ski activities? Does having this amount of options truly distract from the skiing? Our family included an eight-year-old and a seven-year-old. After a week split between Big White and SilverStar, we would have an answer.

Ranger, Shadow, Bandit and their brethren narrowly avoided tripping on their flopping tongues during the half hour that I pretended I was a frontier northerner. When it was over I retired not to my rustic trapper’s cabin, but instead hopped on a gondola back to my well-appointed room in Chateau Big White.

This family ski trip was about to be super-charged by the arrival of my older brother Tyler Merringer, owner of Revolution Cycles in Rossland, B.C., and his two teenage boys Logan and Kian, competitors on the B.C. freeskiing circuit and distant-dwelling heroes to their younger cousins.

When Tyler pulled his pickup into the underground garage, his boys came around the back to “choose their skis.” It’s something you have to do when you need skis for freeski comps, backcountry trips, powder days at the hill or jibbing in the terrain park. It’s always been ability, not equipment that has been my limiting factor on a mountain, but I don’t begrudge those who need specialized gear to get the most out of a sport.

They opted for their park skis, probably good news for me since it meant I’d stand a chance of keeping up to them on the adjacent groomers instead of throwing myself down alpine gullies like Playground in the farther reaches of Big White’s alpine terrain.

The next morning we walked down the hall, picked up our skis from the locker room, continued out a door and found ourselves, without having taken a step up or down, right on the snow-covered lane running through the central village. We glided past the full-service Kids’ Centre, headquarters for the ski school and childcare programs that let Big White boast it’s “Canada’s Favourite Family Resort.” Lessons could wait for another day; today my younger kids would learn by watching their cousins use subtle edge control to make very unsubtle moves down a mountain.

Big White caters to its park riders with a dedicated double chairlift that runs top-to-bottom over a collection of jumps, rails and pipes. We cut a deal with the teenagers that they could ride the park but had to join us for actual skiing above and below by riding the high-speed Bullet Express quad instead of the park chair.

“Join” might be the wrong word. There were next to no turns taken together, with the 16-year-old well in front, a cautious seven-year-old in back and me in between.

One person who disappeared altogether every run was my wife, Ally. We’d meet her at the bottom, and when asked she’d say she had found a stash of well-spaced trees on just the right pitch for her. Learning to ski trees had been a reluctant goal of hers leading up to the trip, so I didn’t want to upset her rhythm, but after half-a-dozen laps, I decided it was time she shared her secret.

She was evasive, then obstinate, not willing to show us where she had been skiing. At first I thought it was greedy territorialism, but when we followed her and saw her skiing through the gaping maw of Ogopogo, I knew it wasn’t greed but shame that kept her quiet.

‘‘Nothing but dips, lips and troughs, perfectly spaced for the young kids… ’’

Ogopogo is B.C.’s answer to the Loch Ness Monster. The mythical beast apparently lives in Okanagan Lake. Big White has built a wooden Ogopogo and scattered its elements through the trees here to entice kids—and some middle-aged women—into the woods to see how much of the monster they can find while learning to not hit trees.

Ergo, Ogopogo for Ally, the terrain park for the teenagers, with the perfect family run topped off with repeated trips down Bumpy Alley, a skinny side trail near the bottom of Bullet Express that is nothing but dips, lips and troughs, perfectly spaced for the young kids (and no one else). You could do it all day long. For a while it looked like we would, but that would be neglecting other aspects of Big White. And by my count there are seven somewhat distinct aspects to the mountain, the base area of which is spread out over 10 km.

Farthest to skier’s-right is the Gem Lake Express, a mammoth chair that runs 2.5 km up Big White’s West Ridge. There’s some open bowl terrain at the top and a few gladed sections, but generally this is the place to stare down long stretches of empty, fall-line corduroy and remember what it’s like to scare yourself.

Farthest east is the Black Forest Express that departs from the new and sunny Black Forest Day Lodge. Runs off Black Forest such as Whiskey Jack and Cougar Alley would prove to be our refuge two days later when whiteout conditions with no visibility forced us off the open runs. With Ally now comfortable chasing Ogopogo’s tail, she happily moved into the Black Forest trees with us, which gave ample visual definition when poor visibility hit.

Logan and Kian never saw too much of the mountain. Since they were only there for one day, they were more concerned with being good cousins than good skiers. We finished the first day centrally and then, after a quick hot tub, got on the gondola that led us downhill to Happy Valley Lodge.

Chuffed is the only way I can explain the look on my eight-year-old son’s face when an instructor gave him a harness, two crampons and two ice axes and told him to climb a 20-metre tower of ice, somehow sculpted to offer different levels of difficulty.

“I never thought I would have gotten way up there,” he said, neck craning, after being belayed back down.

After three or four successful summits, the four kids went to the next-door tube park and my brother and I went indoors for a beer and some of the nightly live music. I was pretty sure I’d only have time for one beer before my jet-lagging, Bumpy Alley-skiing, ice-climbing, tube-parking kids crawled in looking for a bed. As it was, I was the one crawling out the door to announce last run. Ten last runs later, the eldest hoisted the youngest onto his shoulders for the short walk back to the gondola.

I believe she fell asleep slumped forward over his head.

SILVERSTAR

It’s less than a two-hour drive from Big White to SilverStar, travelling back through Kelowna, along Okanagan Lake, through Vernon and 21 km uphill to the colourful mid-mountain village that has made SilverStar famous.

If you drove during a long lunch hour, you could ski them both in the same day, and for a time you could have done so on the same lift ticket.

Australian Desmond Schumann bought Big White in 1985 and SilverStar in 2001. Until 2012, they issued joint passes and shared their marketing departments. For a time, they even offered heli-transfers between the two. But the ownership arrangement ended the same year Desmond Schumann died, with his son, Peter, then in charge of Big White and Desmond’s daughter, Jane Cann, running SilverStar.

Despite my best efforts at muckraking, no one at either resort would dish the goods on what degree of sensational family drama precipitated the split, but you do get the distinct feeling around SilverStar that the resort had spent too many of those years in the shadow of its larger neighbour.

“There was a bit of a rub,” concedes Guy Paulsen, currently SilverStar’s Destination Sales Manager, a position he’s come to after holding almost every other position at SilverStar over three decades.

“Here we have a ski area that’s been around for 30 years, and for 12 years it was hitched to another product. It was just a bit odd, a bit awkward when reaching out to the world. It’s more reasonable to be unhitched,” says Paulsen.

We are eating lunch at Long John’s Pub, ordering off a menu that ranges widely from barbecue to Thai and much in between. SilverStar has little in the way of a day lodge or cafeteria. Instead the skiable “Main Street” is packed with smaller, mostly casual eateries, many independently owned. There is no sense here that one corporate accountant has the keys to every cash register.

The 6,000 beds at SilverStar is just over a third of the accommodation available at Big White, and Paulsen confirms that traffic here is 70 per cent day-skiing, 30 per cent destination visitors. They are still in the business of selling lift tickets.

On our second morning we headed straight to Attridge, the penultimate peak at SilverStar but one that rose right from the doorstep of our slopeside condo. That’s how close to the action you are in this ski-in, ski-out village that’s perched two-thirds of the way toward the top of SilverStar’s 760m vertical drop.

Though rain had fallen on some of the lower elevations, Attridge had gathered 20 cm of surprisingly light snow, delighting all but one of us. Seven-year-old Nora has always been slow and steady on the hills, carefully positioning her skis through each part of her still-novel parallel turns. In short, she did not immediately appreciate the appeal of having one’s skis buried under fresh snow.

“I hate powder snow,” she insisted every time the topic came up of how great the snow was, which was often. Then again, I was experiencing snow up to my buckles while Nora was in above her knees.

Nora might have disagreed with this new experience of powder, but the rest of us were loving it. I thought it strange that the Alpine Meadows Chair wasn’t showing any semblance of a lineup, given that portions of all the lower chairs would have been affected by the rain. I asked the liftee at the bottom why the chair was so quiet. He looked at me like I was new there, then he checked the stats on the electronic scanner he uses to scan lift tickets as skiers load.

“It’s 11:20,” he said. “I’ve scanned 830 skiers so far. This time yesterday I had scanned 150.” (He said all this with an Australian accent, of course, seemingly ubiquitous with every other staff member at both Big White and SilverStar).

So that’s what passes for a run on the powder at SilverStar. My mind reeled when I considered how long powder must last on SilverStar’s distant backside, the 770-hectare billowing Putnam Creek area.

Being of lower elevation I knew the snow in Putnam would have suffered the night before, but the chair follows a southwest bearing as it rises and the SilverStar sun was beaming so I traversed east to take a mid-afternoon trip to work on my goggle tan on Putnam’s Powder Gulch Express.

Black and double-black runs crowded the chair from all angles. There are only five blue runs and a 20-table restaurant at the top, nothing else to distract expert skiers from lapping run after run in this isolated refuge of steep and skinny lines.

Meeting back up with the kids, we tried to get a few cruisers in before the Comet Express closed. We stopped at a junction of Whiskey Jack where a ski patroller had pulled a ribbon across the run, keeping us on the road back to the village.

I started to tell the kids that our day was over, but the watching ski patrol interrupted. “It’s all right. Go ahead,” he said. “We’re a few minutes early for closing. If you want to do something, you just have to ask. That’s how it works here.”

‘‘Apart from the snowmobiling and bowling, full-day lift passes automatically include unlimited access to everything else.’’

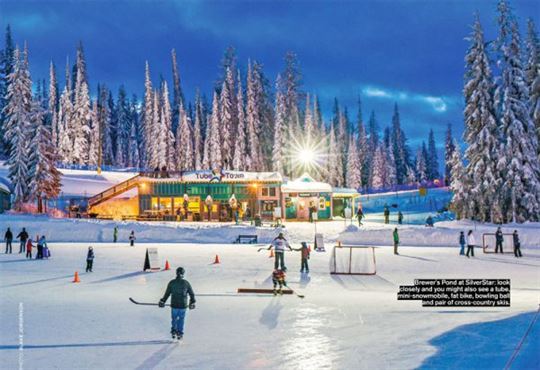

There was little doubt where we’d be heading after that last run. The after-ski activities here are centred around Brewer’s Pond. Those staying in the nearby Firelight Lodge can sit on the balcony with a beer and look down as their children move from skating on the pond, to tubing, to mini-snowmobiling, to fat biking, to snowshoeing. There’s also a bowling alley, or you could even head out on the 105-km network of Nordic trails that are groomed nightly.

And no, the parents won’t have to be throwing money from the balcony. Apart from the snowmobiling and bowling, full-day lift passes automatically include unlimited access to everything else.

There in the fading light beside Brewer’s Pond I ran into an old friend I had only seen a few times since childhood. Paul had grown up in my neighbourhood in Toronto, but had since made the switch to a life on Vancouver Island. He was on a 10-day RV tour of B.C. ski resorts with his son.

We quickly started to reminisce about the March break ski trips our families would take together down to Quebec’s Mont Sutton. They were wonderful weeks of skiing by day and, well, I don’t remember what we did after skiing. I just know it wasn’t tubing, mini-snowmobiling, skating, ice-climbing, dogsledding, fat biking and bowling.

If I had had a mind to gather the kids and tell them how good they have it now, it’s a safe bet they’d have been too busy to listen.

Okay Okanagan

Big White Central Reservations is a good place to start (and maybe finish) planning a trip to Big White. It’s the largest booking agent for the 17,000 available beds at Big White, with packages that include lifts, lessons, rentals, airport transfers and select flights. They also offer special deals during autumn ski show weeks. bigwhite.com

Pick up an all-inclusive POW Pass for discounts on three- and five-day visits to SilverStar (plan days to explore Canada’s largest groomed Nordic ski network). The Call Centre has booking access to 1,200 slopeside beds. The best time to book is July through October. Or look for packages at wholesalers Merit, Ski Can, The Lodging Company and Mountain Lodging. skisilverstar.com